Emancipation & Abolition

The Levy collection has thousands of songs documenting African American history. The songs below are specifically related to emancipation, African Americans in the Civil War, and the abolition of slavery.

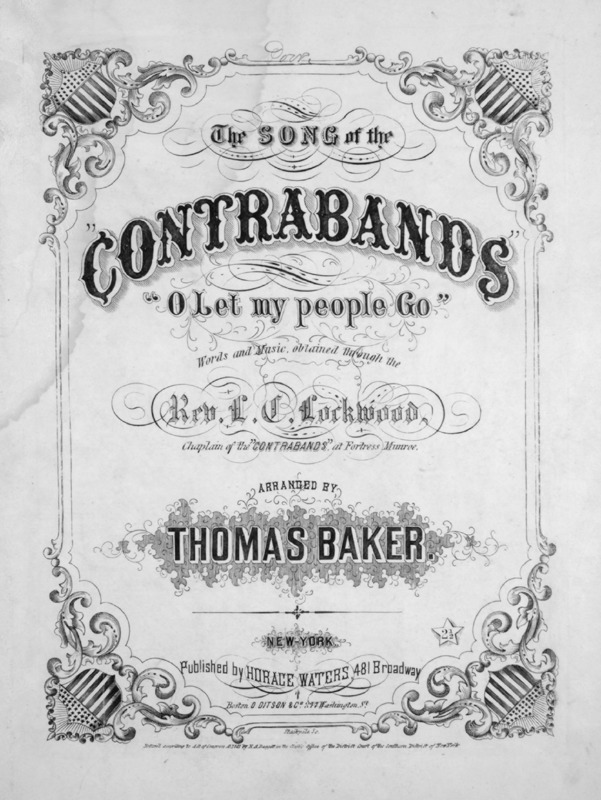

"O Let My People Go" (also called "Go Down Moses") is probably the most widely recognized spiritual that originated in enslaved communities. Published in 1861 (the year the Civil War began), the text is a reference to the liberation of the ancient Jewish people from Slavery in Exodus. The song is also reported to have been used by Harriet Tubman as a code song fugitive slaves would use to communicate when fleeing Maryland, but this has not been proven.

The cover prominently displays the word "Contrabands"-- a reference to a policy of the Union during the Civil War prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. At the outbreak of the war, some fugitive slaves who escaped North were actually sent back to the South. However, the policy soon shifted to declare fugitive slaves "Contrabands of War," -- essentially, captured enemy property. These former slaves often worked as laborers in Union camps, and some were educated and paid wages.

There's also a note on the first page that this song was first heard sung by "contrabands" when they arrived at Fort Monroe, VA. In August 1861, when the US Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861 (declaring that any Confederate property could be confiscated by the Union), a large number of escaped slaves traveled to Fort Monroe. They eventually created a camp outside the fort called the Grand Contraband Camp.

While the song was reportedly sung by escaped slaves, it was arranged by Thomas Baker, a white English musician. In arranging the song, Baker notated what was likely an oral tradition, added piano, and made the melody fit neatly into measures. Unfortunately, the vast majority of music sung by enslaved communities was notated, arranged, and published by white individuals and companies. The most well-known of these publications is Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867 by a group of white abolitionists. This work goes into great detail about the difficulty white arrangers had in accurately transcribing these songs, as the music naturally didn't conform to Western notation. As a result, much of the original performance traditions of these songs were oversimplified or lost completely.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a group of emancipated slaves and students of Fisk University (Nashville), recorded the earliest known version of this song. However, the melody does not match this version, reflecting the widespread and varied tradition of the song. A contemporary recording can also be found here.

Who do you think this song was marketed to?

What did the publisher hope to gain by prominently featuring the word "Contrabands" on the cover?

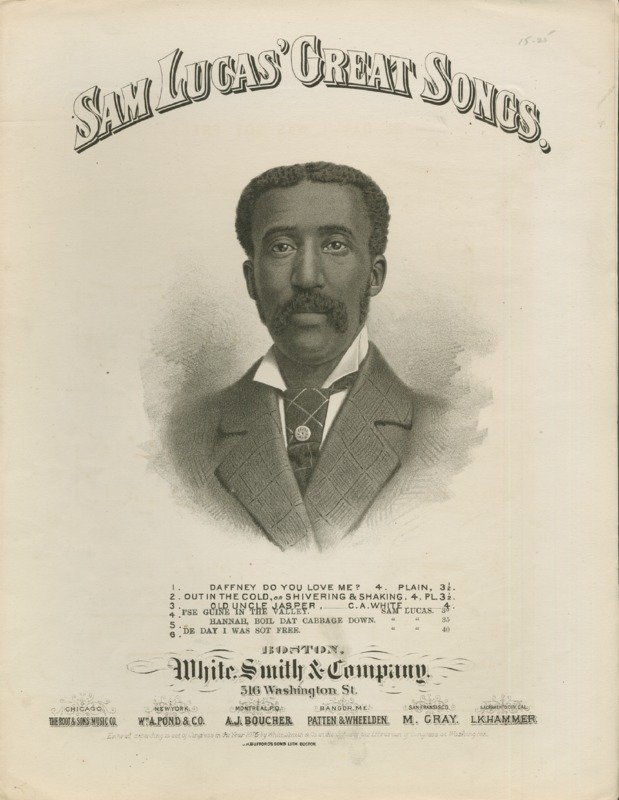

"De Day I Was Sot Free" highlights the difficulty of working in special collections with historic documents, as it is unclear if this is a serious song, or a comic song denigrating African Americans. It was written by Sam Lucas, a composer born to free black parents in 1848. Lucas' career began in minstrel shows, which featured predominantly white performers (but also some black performers) caricaturizing African Americans in blackface. This could imply that this was also a minstrel song.

However, this song was published in 1878, the same year Lucas became the first African American to portrary Uncle Tom in a serious production of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The text is written in a minstrel-dialect, in which words are modified to appear as if they're spoken by an African American. Therefore, depending on how this song is performed, it could be interpreted as a minstrel song or a serious anti-slavery one.

A serious rendition of the song can be found here.

Do you think this was intended to be a serious song, or a minstrel one?

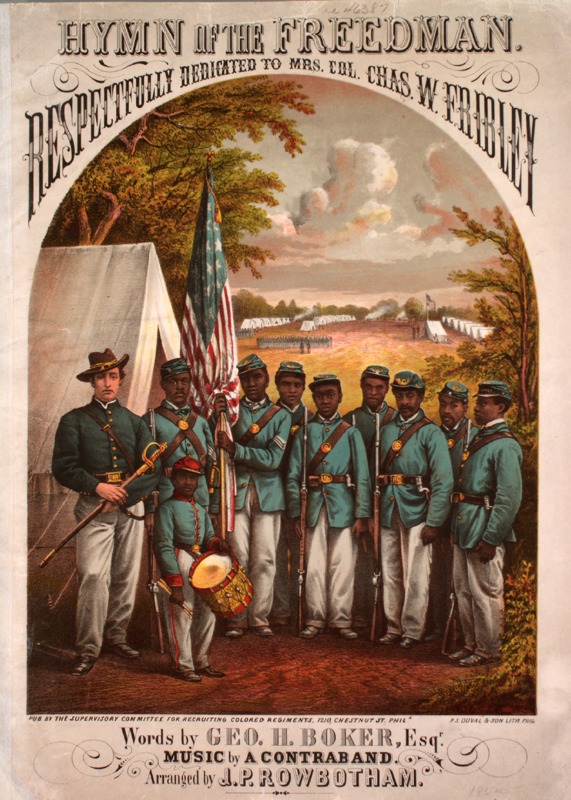

With the emancipation proclamation in 1863, black men were welcomed into the Union army. "Hymn of the Freedman" is evidence of the North's recruitment efforts-- note the highly decorative (and likely expensive) cover. A report from the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia notes $33,000 was raised in 1864, the year this song was published (~$540,000 today). You can read more about black soldiers in the US military here.