Léon Bakst

Theatrical designer Léon Bakst’s (1866-1924) works provide a window into an art intended to be ephemeral. The sketches provide only a small impression of the full experience of watching the influential ballet company, the Ballets Russes (1909-1929), whose avant-garde productions promoted a new generation of European and American dance enthusiasts. The company's edgy design ethos centered around a belief that art should be united within a production where choreography, music, set, costume, and lighting were considered equally, contrasting with other ballet productions that followed predictable artistic patterns. In 1920, Vanity Fair asked Bakst if he regretted that his work would disappear when a production’s run ended, to which he reportedly shrugged and replied, “It is all comparative: only the creative force in the artist’s soul survives.”

Take some time to look closely at these designs, imagining what they might have looked like when moving on a stage to music.

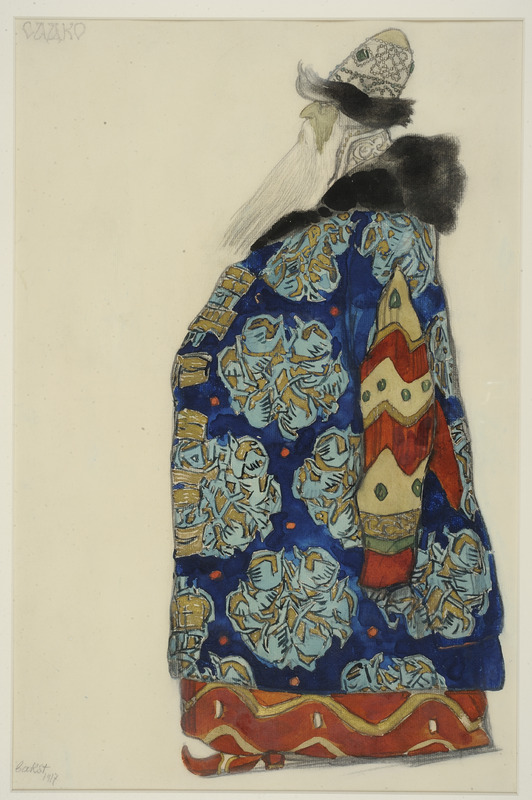

This pair of costumes was intended for a 1916 production of Aladdin staged in Paris. These costumes emphasize the exoticism that was prevalent in Bakst’s work. Drawing heavily from Persian sources, Bakst used historic art and architecture surrounding the culture of the ballet’s setting. On his design process, Bakst wrote: “As for me, I will tell you how I go about designing: I study the decoration of the period of the piece which I am designing; I choose the most significant element; I adopt it and I repeat it on the materials, the architecture, the jewelry. The decoration thus become a leit motiv [sic]; and I achieve a unity not only of colour but also of line.”

Exoticism was a popular artistic style among Western art and theatre in the early 20th century. Described by Oxford Reference as, "a romanticization, fetishization, and/or commodification of ethnic, racial, or cultural otherness," exoticism highlights both conscious and unconscious imperialism felt by both Western artists and artistic consumers. Composers, designers, and choreographers romanticized Middle Eastern and Asian source material for the consumption of European audiences.

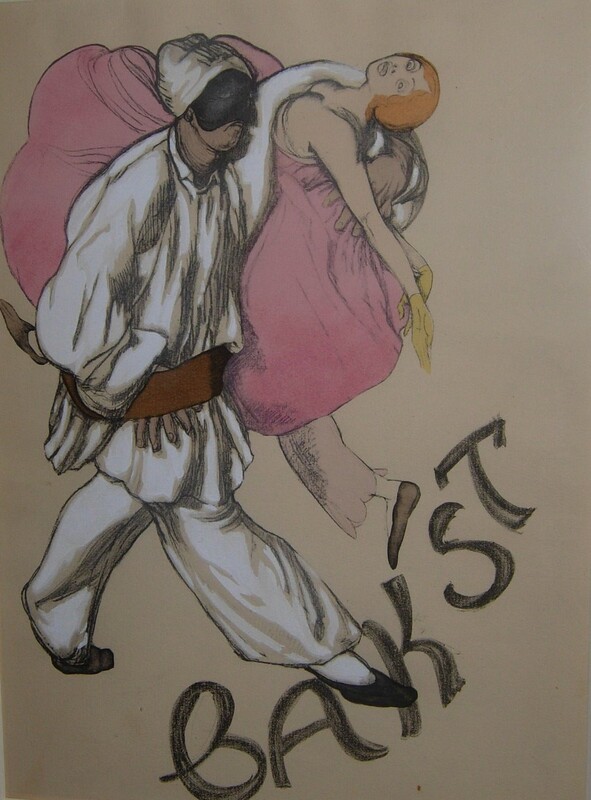

These designs were for a 1917 Ballets Russes production staged in Rome. Based on a comedy by Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793), the performance focuses on a complex love affair involving the lead character, Constanza. Even in the costume sketches, Bakst projects a playful air and utilizes cheerful colors to emphasize the comedic intent of the ballet.

This costume represents one of many designs completed by Bakst for an unrealized production of Sadko in Paris. The story is set in 12th century Russia and revolves around the titular main character’s fortune-seeking journey. Bakst left Russia in 1912 and never returned after the rise of Bolshevism. Still, his love for his native country inspired many of his designs and is especially present in this character’s costuming.

These set designs were completed by Léon Bakst for a 1916 production of Sleeping Beauty for ballerina Anna Pavlova’s (1881-1931) company in New York. This was the second of three Sleeping Beauty productions designed by Bakst, concluding with the Ballets Russes’ 1921 London production. His 1921 design was a critical success. The Daily Mail reported, “The major splendour was Bakst's. All the colours of all jewels, of all sunsets, of all flames, are in these stage pictures…Only babes in the star Sirius can have christenings like last night's Princess, such orange saffron and moss-green of the court ladies, such glistening azure and ermine of the royalties' robes.”

When designing Evergreen’s theatre, Léon Bakst created abstract patterns and stencils derived from Russian folk and Native American designs. After creating the design, he employed assistant painters to implement his vision. Alice Warder Garrett’s niece, Louise Thoron MacVeagh recalled,“Mr. B would appear around 9:30am in a stocking cap covering his newly dyed red hair, and the painters and I would stand at attention for his comments (always kindly, though exacting)...He told me that when he painted scenery for the Russian Ballet, on arrival at the theater in the morning, all painter assistants stood at attention, brooms on the alert and pails of paint ready, and at his word, paint flowed, brooms went into action and scenery was created.”