The Bakst Theatre

Léon Bakst (1866-1924) was born Lev Samoylovich Rosenberg into a middle-class Jewish family in Grodno, now in present-day Belarus. His family moved to St. Petersburg soon after he was born. After his parents’ divorce, Bakst eventually adopted his maternal grandfather’s name. He began his art education at the esteemed St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. However, Bakst spent only 18 months at the school because his realistic painting— Madonna Weeping Over Christ, created as a response to anti-Semitism at the school—offended the judges and resulted in his expulsion.

Bakst found a new artistic home among likeminded Russian artists such as Alexandre Benois (1870-1960) and Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929) who formed a new artistic movement, Mir iskusstva, or World of Art. The group sought to promote art inspired by the work of Russian old masters and folk art. In 1910, several members of the group, including Bakst, were forced to relocate to Paris. The designer recalled, “I faced my attackers and now, at the peak of my happiness, I am expelled from the city of my birth, from St. Petersburg, and not one painter from the Academy of Fine Arts has whispered a word to say that it is a disgrace; a disgrace for the city of my birth, a disgrace for the country which I tried my best to glorify to the world.”

In 1901, at the age of 35, Bakst designed his first work for the theatre. During the next 23 years, until his death in 1924, his work for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes revolutionized the theatre and influenced fashion and interior design on both sides of the Atlantic. Many of Bakst’s designs remain in popular memory, perhaps most famously his costume design for Anna Pavlova’s Swan Lake. His costumes were known for their radical use of color and daring designs. The New York Times obituary for the artist summarized his career by stating he “discovered the strong joy of barbaric color, the intoxication of the tortured line, and set all the world aglow with a flame that was of the senses wholly.”

Alice Warder Garrett grew up with a passion for fine and performing arts. She first met Bakst in 1914 when she was in Paris with her husband, the diplomat John Work Garrett. In a letter to her sister, Garrett described the artist as “one of the most strange human beings that I have ever known.” Quickly, the artist and patron began a professional relationship and personal friendship that would last for decades.

Garrett served as a patron for Bakst’s career. Starting in 1919, she also acted as his agent in the United States. In April 1920, she arranged an exhibition of 84 of his watercolors, drawings, and stage designs at M. Knoedler & Co. Gallery in New York and promoted the exhibition through an article she wrote that was published in Vanity Fair. After the New York exhibit closed, she arranged for another at the Maryland Institute of Art (now the Maryland Institute College of Art, or MICA) and managed the sale of his works to American collectors for years.

The Construction of the Bakst Theatre

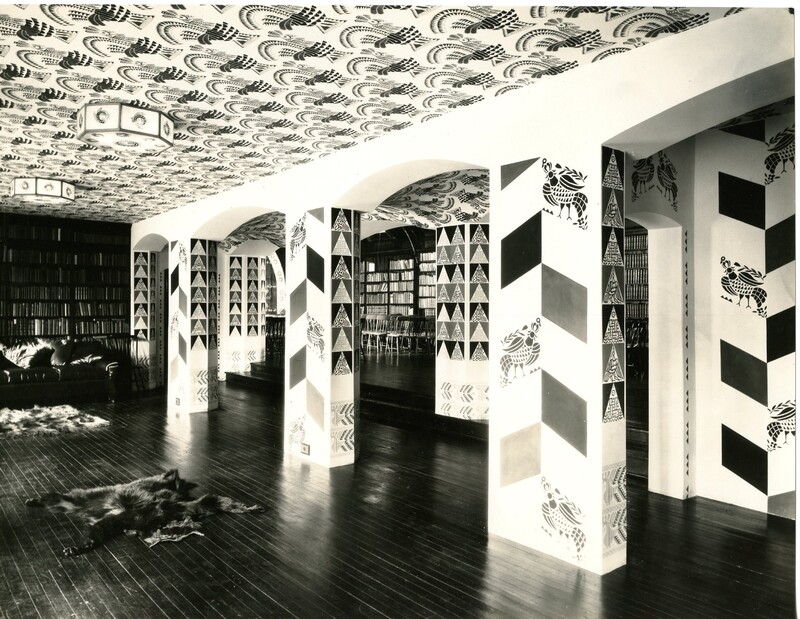

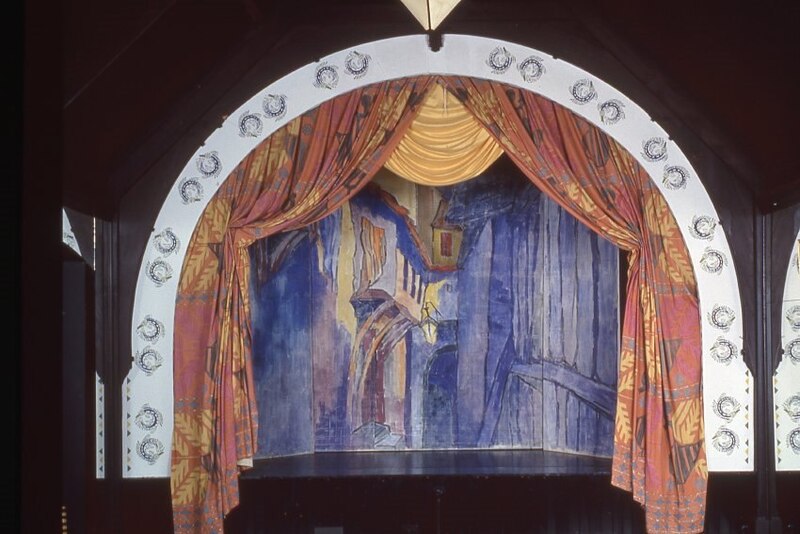

In the winter of 1922-1923, Léon Bakst designed the theatre at Evergreen as an act of gratitude toward Alice Warder Garrett for her assistance in promoting his career. Bakst decorated the space with folk art images from his native Russia, an approach reminiscent of his earlier design work for the Ballets Russes. With a team of set painters who executed his designs, Bakst’s theatre was complete by May 1923.

Many of the designs used in the theatre were taken directly from Charles Holme’s Peasant Art in Russia (1912). This book, which Bakst found in the Garretts’ extensive library, contained examples of traditional folk motifs on carved cake-molds, embroidered bed curtains, woven textiles, and architectural elements. Bakst adapted some of these designs into colorful gouache drawings, which were used to make stencils.

Painting assistants decorated the ceiling, walls, and columns of the theatre lobby with the stencils, as well as the windowpanes, window frames, and ceiling lamps. These same images also were stenciled on the proscenium arch of the stage and on various framing elements throughout the theatre proper. One of the set painters, Alice Warder Garrett’s niece, Louise Theron MacVeagh (1899-1986), recalled, “The first day he presented me with a sketch to be enlarged for a scenery. I was a bit startled when he said in French, ‘Mademoiselle, tack the canvas on the floor, attach your charcoal to a yardstick, also your brushes, and then draw and paint my sketches as I have planned them…Mademoiselle, you will never be another Bakst but I will teach you all I know.”

Bakst's Scrim Designs

Theatrical productions are, by their nature, ephemeral and can only live on in the memories of the audience. When the production concludes, sets are struck from the stage and either recycled into new productions or thrown away. When Evergreen’s Theatre was created, Léon Bakst also designed three stage sets to be used by Alice Warder Garrett for performances in the space. Their survival offers present-day visitors a rare glimpse into the early 20th century theatrical experience.