Difficult History in the Levy Collection

Music has served countless purposes in American history, ranging from a catchy tune or work of art to a rallying cry for a protest movement. Ultimately, music has spurred on causes such as suffrage and abolition, but it has also supported more nefarious ideologies, including the movement for White supremacy. While the Levy collection specializes in music from more mainstream threads (vaudeville, Broadway, etc.), Lester also sought to preserve songs from the darker corners of US history so students and scholars could confront them

While these racist, sexist, and xenophobic songs in the collection do not deserve public display, they are a critical part of the United States’ social and cultural history and continue to be used by scholars in examining the history of racism in American popular culture. In order to best contextualize these songs, we have included them in this digital exhibit.

The collection’s holdings of racist material begin with Blackface minstrel music, progressing through Confederate songs and into the Ku Klux Klan. Recognizing the important role these songs played in American history, Levy sought to preserve them so they could be confronted by students and scholars.

Content warning: This section contains explicitly racist, sexist, xenophobic, and other uncensored offensive language. We have included these songs not to promote or otherwise celebrate these materials, but to use items of intolerance as teaching tools.

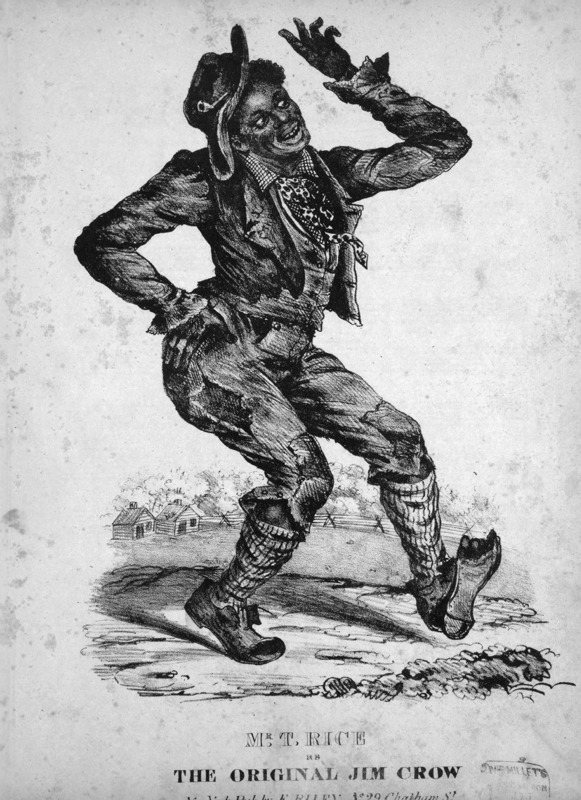

The minstrel show was a racist form of theater that surfaced in the 19th century, featuring skits of White performers in Blackface makeup. These skits, built upon caricatures of African Americans, were interspersed with instrumental songs, ballads, and dances. Widely recognized as the first unique form of entertainment in the United States, minstrel shows quickly became the dominant form of American performance for decades.

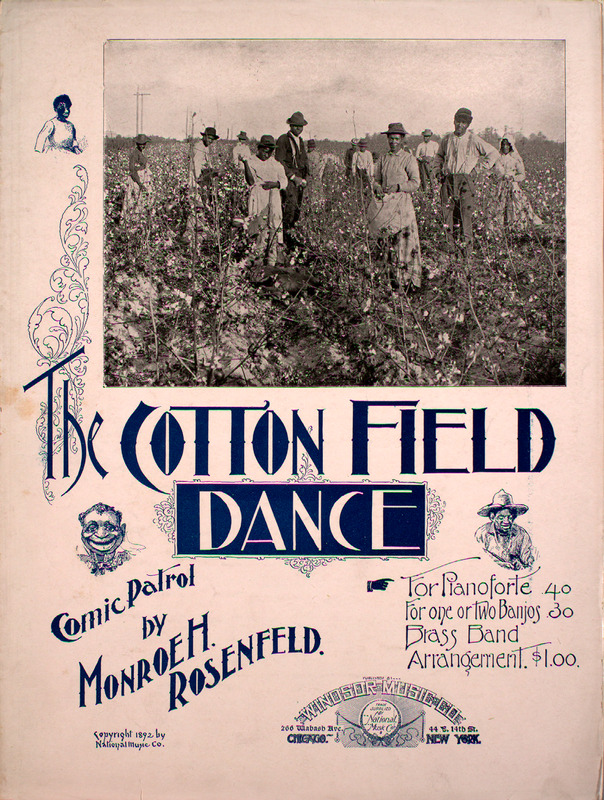

Numerous minstrel songs depicted enslaved persons as joyful or mischievous. The Cotton Field Dance appears to have a photo of enslaved persons on the cover, as well as caricatured cartoons of them below the title. The composer, Monroe H. Rosenfeld, was well-known at the time, composing more than 1,000 songs and coining the term "Tin Pan Alley." The style of the music is upbeat, with popular ragtime rhythms similar to the music of Black composer Scott Joplin, implying the cotton field was a place of joyful dance.

Jim Crow was originally a minstrel character, dressed in rags and lacking manners or wit. The character was made famous by Thomas Dartmouth ("Daddy") Rice, often called 'the father of American minstrelsy.' Jim Crow would eventually come to symbolize the laws that enforced racial segregation in the United States.

Three months into the Civil War (1861-1865), the Confederate Constitution was adopted by Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. The document states, "In all such territory the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the Territorial government."

Music was a key tool in recruitment and maintaining troops' morale-- one Southern music publisher noted, "The South must not only fight her own battles but sing her own Songs and Dance to music composed by her own children."

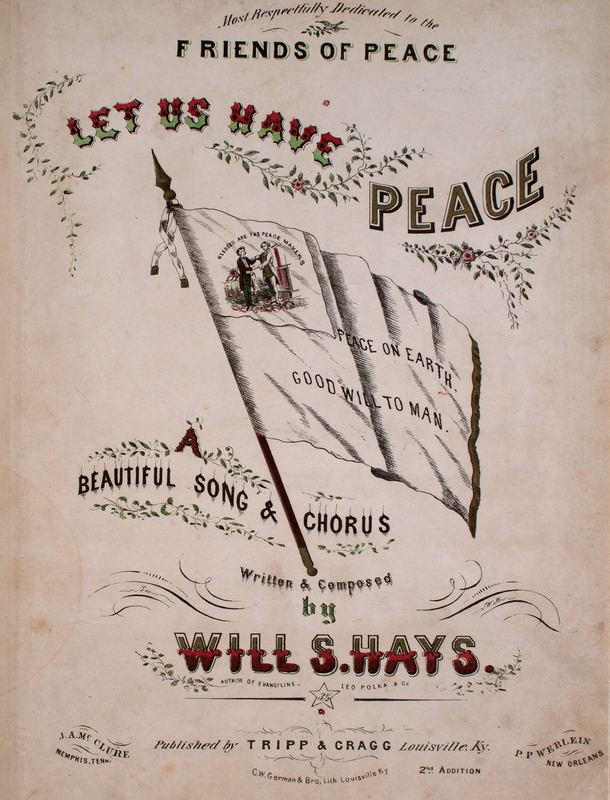

"Let Us Have Peace" was published in Louisville, KY in 1861 (the year the Civil War started). The cover is filled with 'peaceful' imagery- the song is dedicated "most respectfully to the friends of peace," and shows an early Confederate flag with the words, "Peace on earth, goodwill to man." There is also an image of two brothers shaking hands. The lyrics appear to be anti-war, asking, "America, beloved land, once beautiful and bright, oh why should friendship turn to hate, oh why should brothers fight?" However, a later lyric claims "Tis worse than vain for you to try to subjugate the South." This juxtaposition of a plea for peace with a warning against 'subjugation' might make an audience feel proud and powerful, while ignoring responsibility for the actual cause of the war.

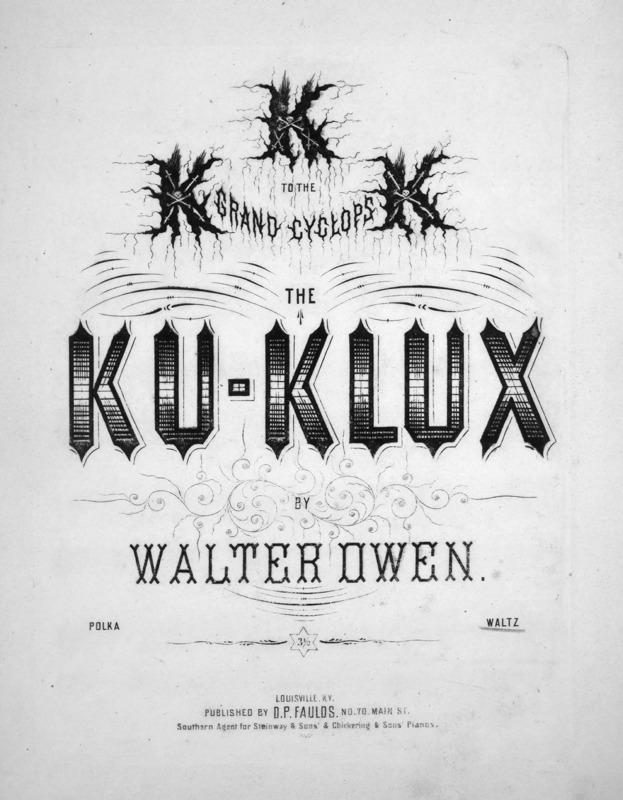

Music has served numerous functions throughout the history of the Ku Klux Klan. Songs were used for recruitment, social functions, propaganda, and ceremony.

This song, dedicated "To the Grand Cyclops" in intimidating font, was composed by Walter Owen. It was published as both a polka and waltz in Louisville, Kentucky 1868. This places it in the first iteration of the Klan, which was originally composed of ex-Confederate soldiers. The fact that this is a dance without lyrics might imply it was used in social functions. The waltz is quite elaborately composed (perhaps inspired by the waltzes of Johann Strauss II), masking fierce hatred behind a beautiful melody.

Modern hate music

Of course, sheet music is no longer a dominant form of social media, and music's role in the White supremacist movement has significantly changed. However, music still plays a key role in networking and recruitment. Social media platforms including YouTube and Facebook face an endless battle to remove hate music online, including White supremacist metal.

While the elimination of White supremacist music may not be possible, the unmasking of it is. In the preface to his compilation Ku Klux Klan Sheet Music, author Danny Crew warns:

"It is my hope that this book will serve as a warning for us to be wary of quick calls to partisanship, patriotism, religion, and self-promotion. While some of these causes will be legitimate, it is incumbent on us all to view such calls with a healthy degree of skepticism and it is our duty to question for hidden motivations. Evil wears many disguises and it is up to us to see beyond the public mask presented by such groups and individuals if we are to prevent another Ku Klux Klan."

Critical Cataloging

The Levy Collection continues to be examined and updated in order to more honestly and clearly address the history of racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia in American popular culture. Ongoing projects are currently attempting to identify and promote Black contributors in the collection, provide more context to the difficult history contained in its pages, and reevaluate descriptions of minstrel material in the university’s Special Collections.

Sources and Further Reading

-

Abel, Lawrence E. Confederate Sheet Music. McFarland & Company, 2011.

-

Burnim, Mellonee V. and Maultsby, Portia K. African American Music. Taylor & Francis Group, 2006.

-

Crew, Danny. Ku Klux Klan Sheet Music: An Illustrated Catalogue of Published Music, 1867-2002. Mcfarland, 2003.

-

Edwards, Bob and Corte, Ugo. White Power Music and the mobilization of racist social movements. Music and Arts in Action. Vol 1, issue 1 June 2008.

-

Moynihan, Michael and Soderland, Didrik. Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground. Feral House, 2003.

-

Simi, Pete and Futrell, Robert. American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement's Hidden Spaces of Hate. Rowman & Littlefield, Maryland. 2015.

-

Toll, Robert. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford University Press, 1977.