Harlem Renaissance

“To my mind, it is the duty of the younger Negro artist… to change through the force of his art that old whispering ‘I want to be White,’ hidden in the aspirations of his people, to ‘Why should I want to be White? I am a Negro—and beautiful!”

-Langston Hughes, The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain

For Black writers, artists, and musicians, the Harlem Renaissance was a period of cultural rebirth, reinvention, and redefinition. The era saw Black poetry, graphic art, and prose reaching impressive heights and broader audiences. Whereas Black composers and performers had previously been expected to conform to White audiences’ expectations of behavior, appearance, and sound, these musicians broke free from musical and social molds to inspire an era of protest.

In 1931 Duke Ellington wrote: “What we could not say openly we expressed in music, and what we know as ‘jazz’ is something more than just dance music.”

The songs below represent just a few of the poets, artists, and musical icons that emerged during this era.

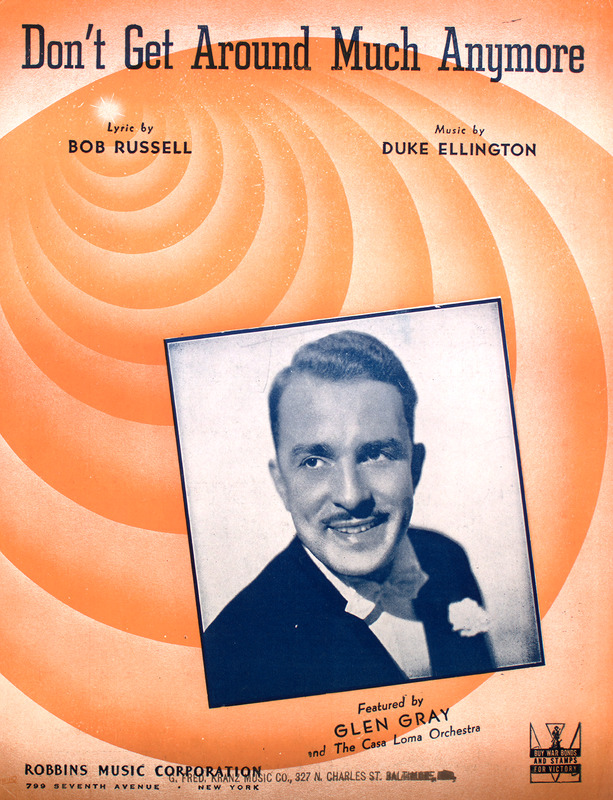

Duke Ellington, virtuoso band leader and jazz pianist, published this hit in 1942. Ellington became famous for his performances at Harlem’s Cotton Club in New York. He would eventually tour Europe and the US South, often staying overnight on trains to avoid racial discrimination in hotels.

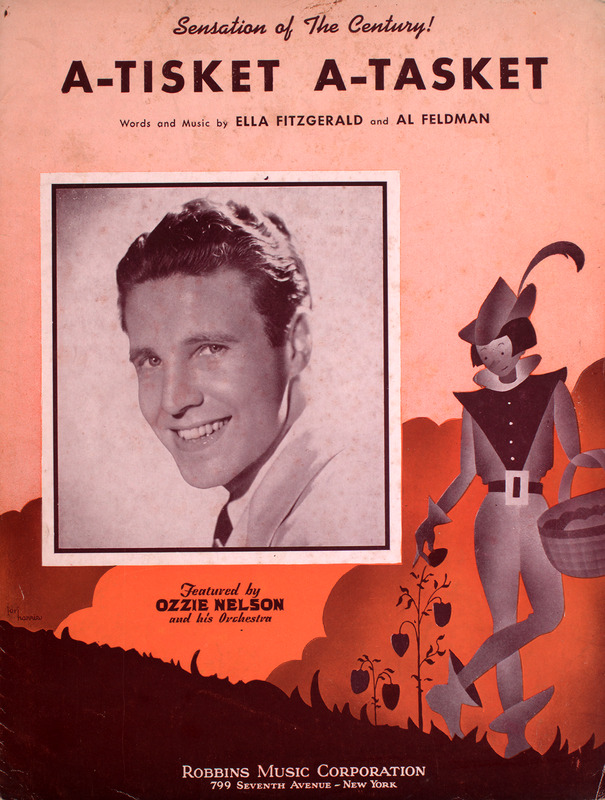

Originally a nursery rhyme, A-Tisket A-Tasket was popularized by Ella Fitzgerald in 1938—it was her first #1 hit with a band. Fitzgerald, one of the most popular jazz singers to ever take the stage, performed frequently at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom and won 13 Grammy awards in her career.

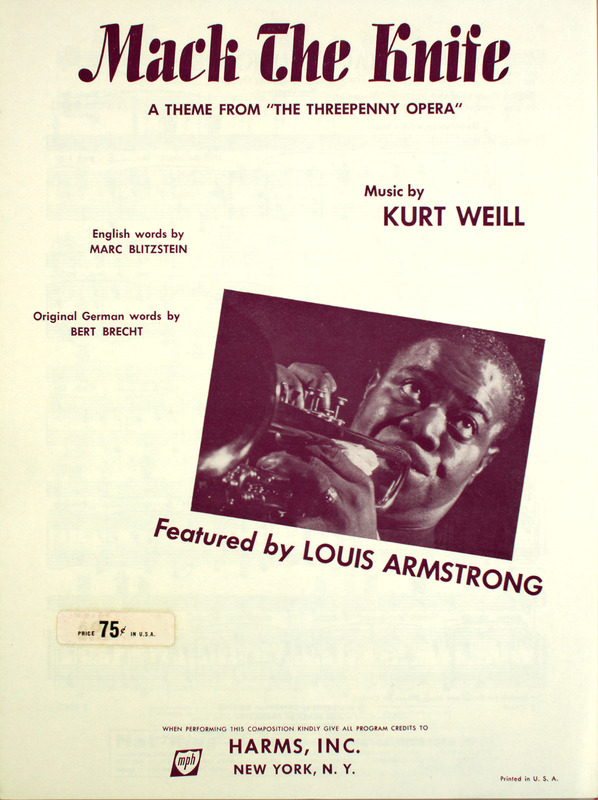

This jazz standard was a collaboration between Andy Razaf, Thomas “Fats” Waller, and Harry Brooks. Written for the musical Hot Chocolates, it had its first performance at Connie’s Inn in Harlem and eventually became a go-to for trumpet legend Louis Armstrong.

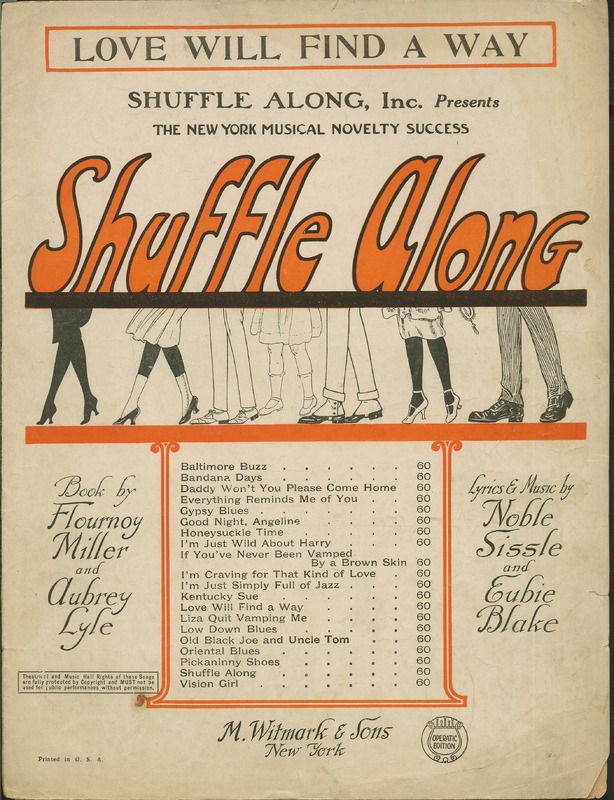

Love Will Find A Way debuted in the musical Shuffle Along, the first Broadway hit to feature an all-Black cast and creative team. The close collaboration between Noble Sissle and Baltimore’s own Eubie Blake helped legitimize the African American musical and proved to skeptics that audiences would pay to see African American entertainment on Broadway.

This cover photo of Louis Armstrong is a marked departure from the racist marketing practices that dominated sheet music over the previous 100 years. Rather than minstrel imagery, the publisher instead chose to capitalize on Armstrong’s renown to promote the song.

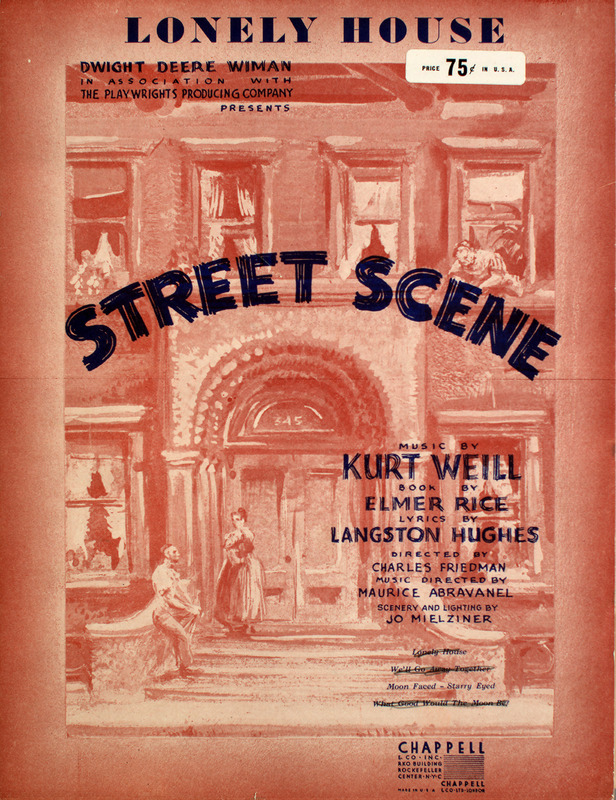

The works of poet Langston Hughes—heavily influenced by jazz— were an enormous contribution to the Harlem Renaissance and its music. Hughes wrote the lyrics to this opera with the goal to “lift the everyday language of the people into a simple, unsophisticated poetry."