Protest Movements

More than just a melody, sheet music served as an early form of social media, spreading messages through catchy tunes and attracting passers-by with colorful covers. Historically, content creators from composers and movie producers to today's Instagram advertisers have known that music can evoke emotions that words can’t— often without audiences realizing it's happening.

It is therefore no surprise that songs have been published by members of various reform movements to inspire masses to join and to provide cultural legitimacy for that movement.

Here you’ll find songs from four protest movements, all of which overlapped and are still in motion: emancipation, labor, women’s suffrage, and temperance (abstinence from drugs and alcohol). You’ll also find songs from opposing sides of the movements—each employing colorful covers and stirring melodies to inspire passion and zeal for their respective causes.

Think of a movement you care about or participate in. How have you been moved by music to contribute or participate in that movement?

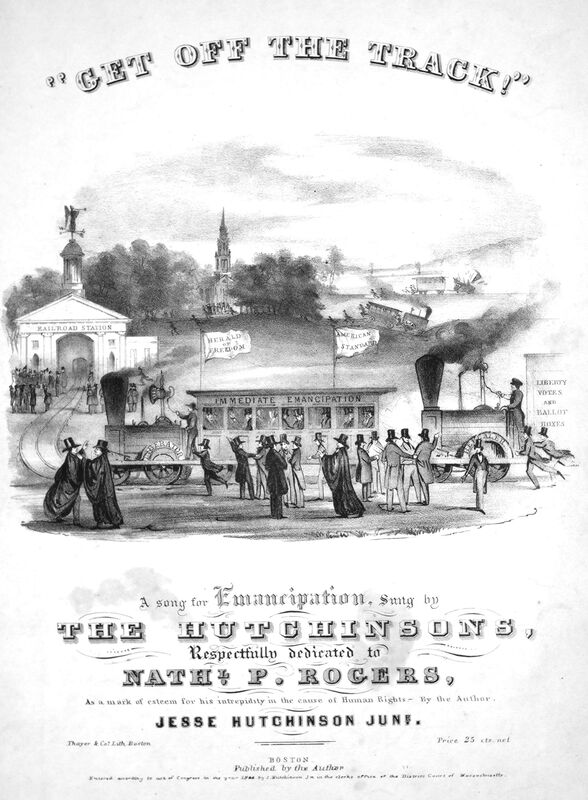

The Hutchinson Family Singers were a touring musical group popular in the 1840s. Rather than singing minstrel songs, which were at their peak popularity, the Hutchinsons chose instead to perform music from social causes including emancipation, prohibition, and women’s suffrage.

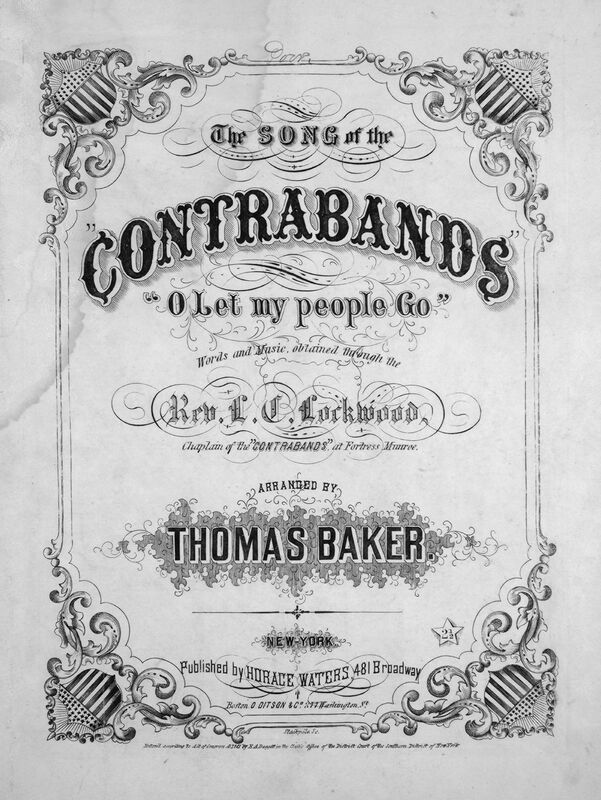

O Let My People Go (also called Go Down Moses) is probably the most widely recognized spiritual that originated in enslaved communities. The text is a reference to the liberation of the ancient Jewish people from slavery in Exodus. The song is also reported to have been used by Harriet Tubman as a code song fugitive slaves would use to communicate when fleeing Maryland, but this has not been proven.

The cover of this version (published in 1861) prominently displays the word "Contrabands"-- a reference to a policy of the Union during the Civil War prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. At the outbreak of the war, some fugitive slaves who escaped North were actually sent back to the South. However, the policy soon shifted to declare fugitive slaves "Contrabands of War," -- essentially, captured enemy property. These former slaves often worked as laborers in Union camps, and some were educated and paid wages.

There's also a note on the first page that this song was first heard sung by "contrabands" when they arrived at Fort Monroe, VA. In August 1861, when the US Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861 (declaring that any Confederate property could be confiscated by the Union), a large number of escaped slaves traveled to Fort Monroe. They eventually created a camp outside the fort called the Grand Contraband Camp.

While the song was reportedly sung by escaped slaves, it was arranged by Thomas Baker, a White English musician. In arranging the song, Baker notated what was likely an oral tradition, added piano, and made the melody fit neatly into measures. Unfortunately, the vast majority of music sung by enslaved communities was notated, arranged, and published by White individuals and companies. The most well-known of these publications is Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867 by a group of White abolitionists. This work goes into great detail about the difficulty White arrangers had in accurately transcribing these songs, as the music naturally didn't conform to Western notation. As a result, much of the original performance traditions of these songs were oversimplified or lost completely.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a group of freed persons and students of Fisk University (Nashville), recorded the earliest known version of this song. However, the melody does not match this version, reflecting the widespread and varied tradition of the song.

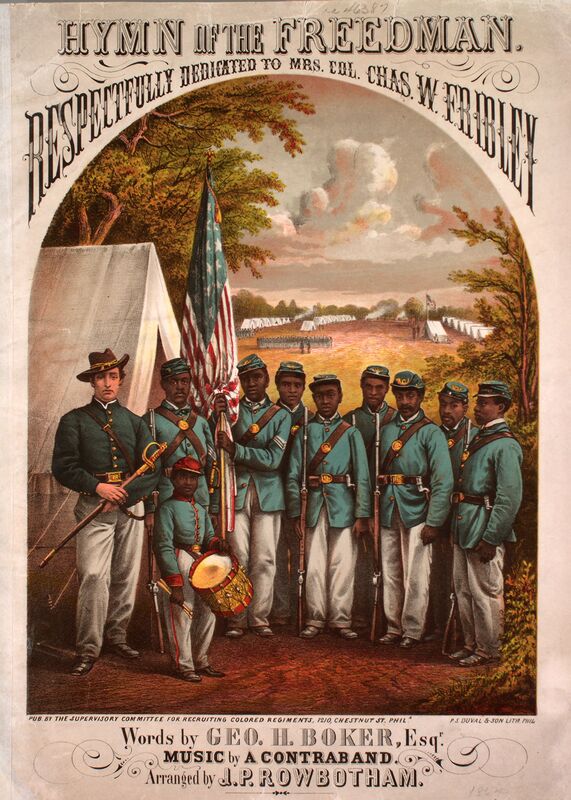

With the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Black men were permitted to join the Union army. Hymn of the Freedman is evidence of the North's recruitment efforts-- a report from the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia notes $33,000 was raised in 1864, the year this song was published (~$540,000 today). The cover goes out of its way to avoid the derogatory minstrel imagery that pervaded the industry— it also claims to be written by a “contraband,” implying an emancipated composer.

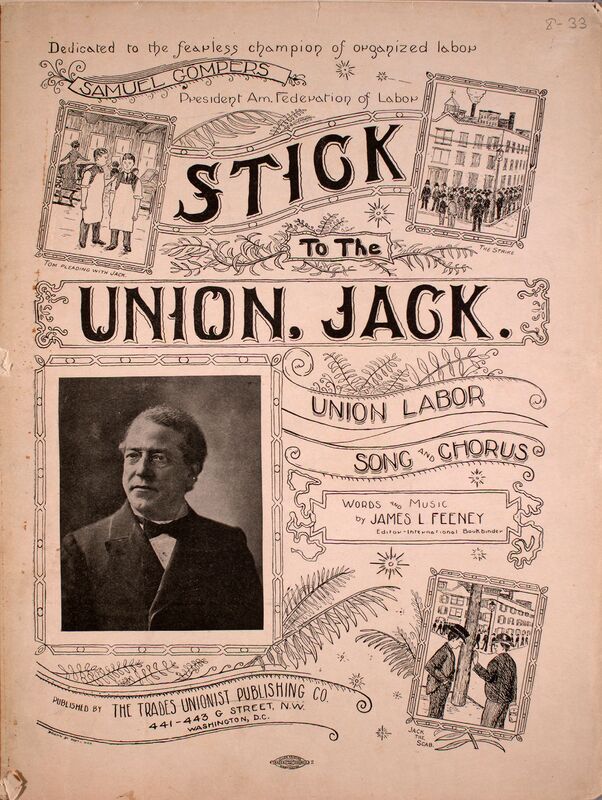

This song is dedicated to the president of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), Samuel Gompers, and was published in 1904 in Washington D.C.

The main character of the song, Jack, is a scab-- someone who crosses a picket line to fill in at an organization so it can continue to function. Jack is then shunned by his colleagues (this story is also illustrated on the cover). The song is published by the Trades Unionist Publishing Co., which clearly had a vested interest in successful strikes.

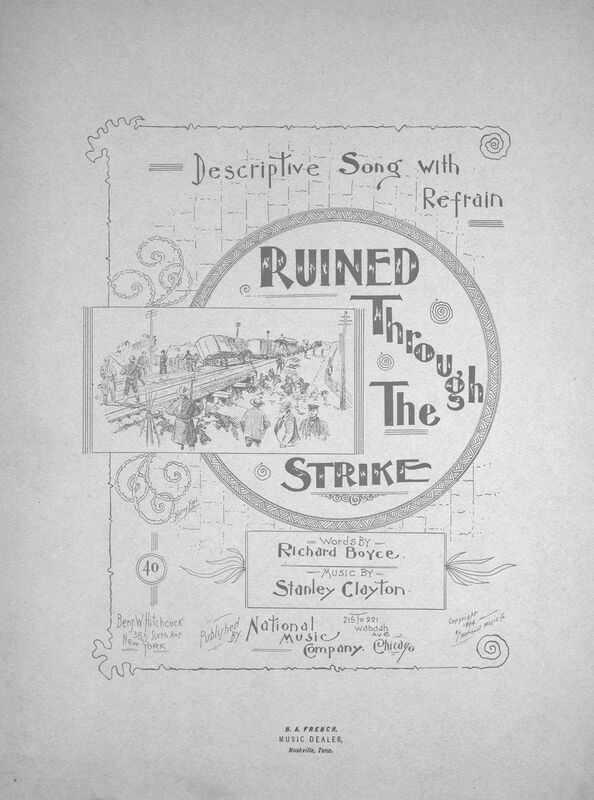

Likely inspired by the fatal Pullman Railroad Strikes in Chicago 1894, this song tells the dramatic story of a protester being shot by soldiers. In stark contrast to Stick to the Union, Jack, the aim here is to scare listeners out of participating in strikes.

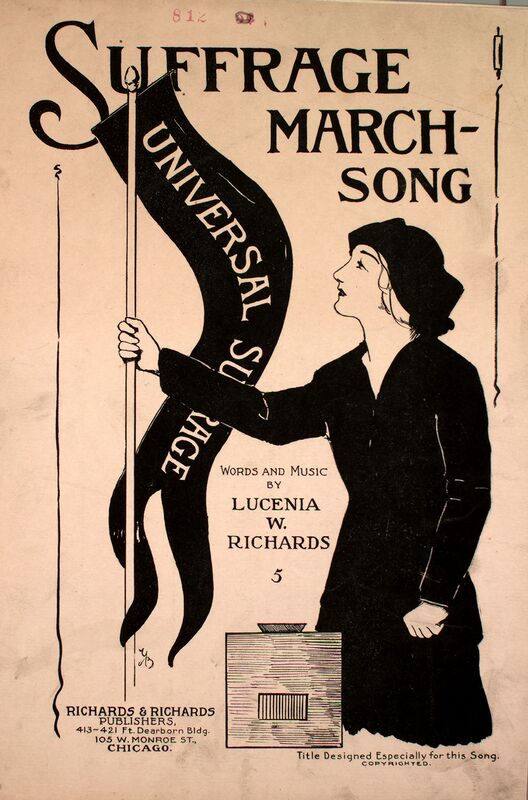

This pro-suffrage song appears to be self-published by Lucenia Richards in Chicago. The inner cover features a stirring call to action from the composer: “may its martial strains awaken the best fires that burn within us.”

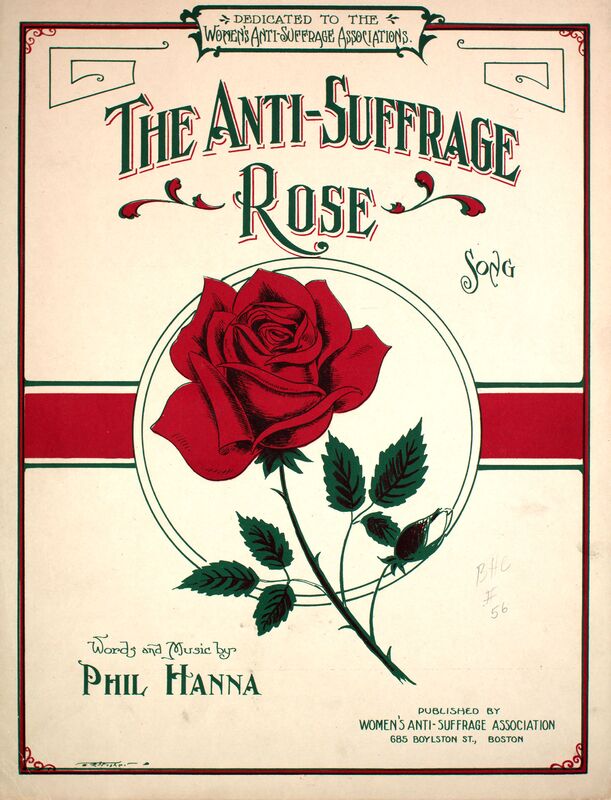

Published by the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association, this cover features the red rose: an anti-suffrage emblem. The lyrics begin, “Suffragists say… they’ll win the coming fight; twixt you and me, I don’t agree, we’re going to show them who’s right!”

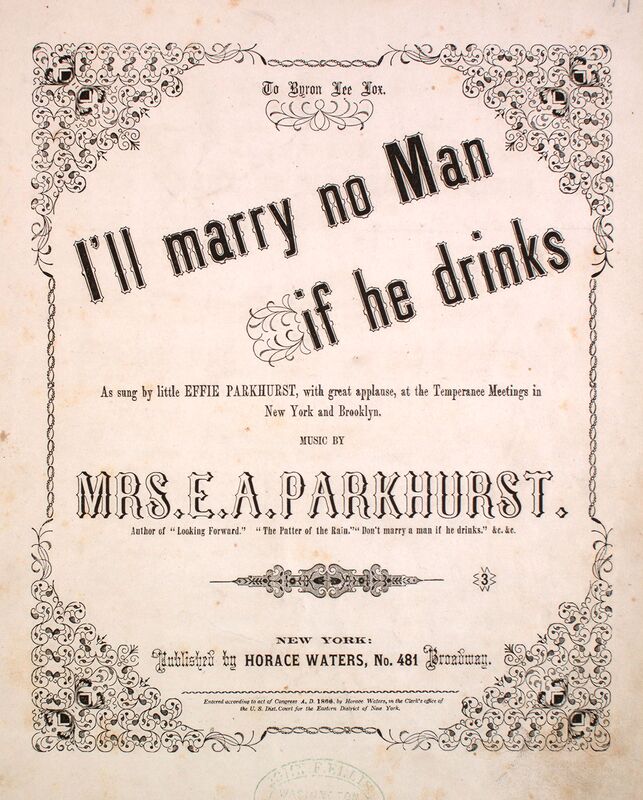

This early prohibition song was published in 1866 by Susan McFarland Parkhurst. As women were leaders in the temperance (anti-alcohol/drug) movement, the lyrics are performed from the perspective of a wife disavowing any suitor if he drinks alcohol.

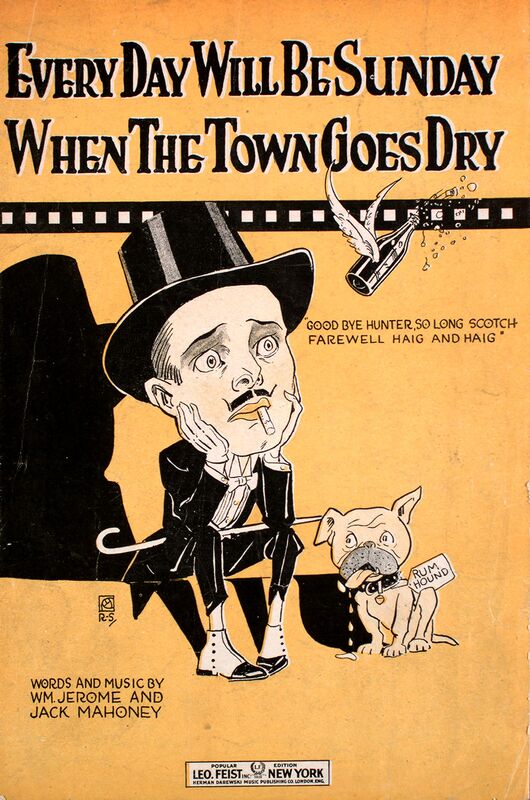

This pro-alcohol cover depicts a well-dressed gentleman sadly watching his beer fly away. The song was published in New York, a city infamous for its lack of enforcement of prohibition. By 1930, the police commissioner of the city estimated that there were at least 30,000 speakeasies (illegal bars).