Songs of War

Music has been used in warfare since ancient times, from synchronizing marches to coordinating cannons. Inspiring melodies and stirring rhythms have been manipulated in thousands of ways to inspire recruitment, maintain troop morale, rally the country around a cause, and comfort bereaved families.

The songs below represent these various uses of music through two centuries of war in the United States: the Revolutionary War, Civil War, The First and Second World Wars, and the Vietnam War.

How have you noticed music being used in relation to warfare or violence today?

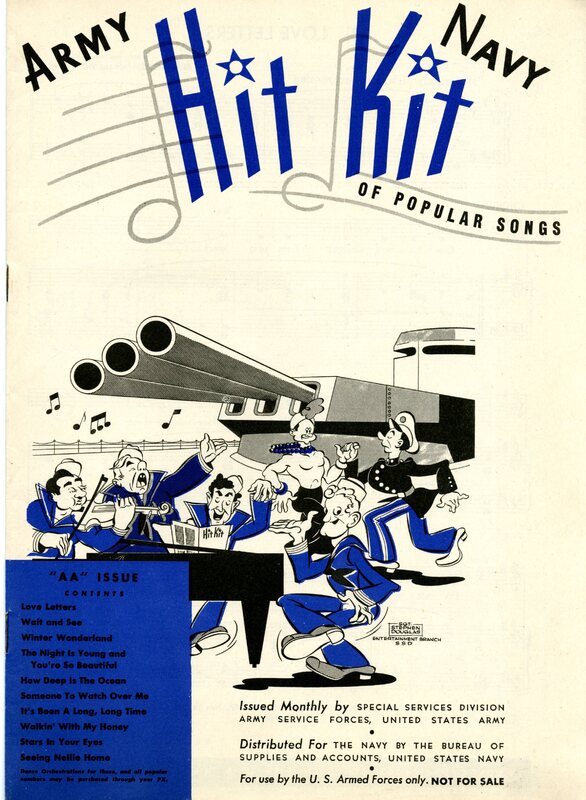

Music has consistently played an important role in maintaining soldier morale, including celebrity visits and military bands. These songs were distributed to soldiers during World War II, containing simplified piano parts to allow troops to more easily perform them.

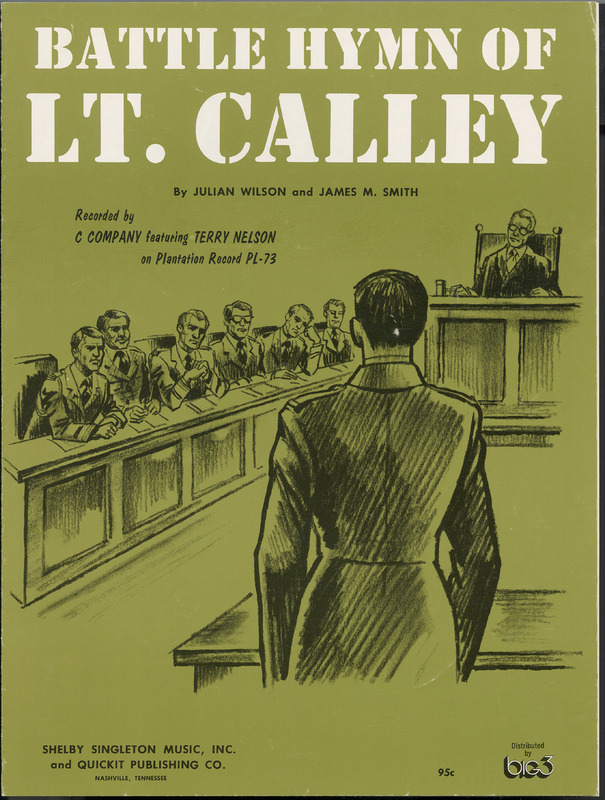

This song from the Vietnam War was published in Nashville in 1971. It's one of the most recently published songs in the Levy collection. The song is a reference to the My Lai Massacre, in which US soldiers killed between 300 and 500 unarmed Vietnamese civilians. 26 soldiers were charged with criminal offenses, but only Lt. Calley was convicted-- he was found guilty of murdering 22 villagers and received a life sentence, serving only 3.5 years under house arrest. This was composed in support of Calley, portraying him instead as a patriot that was just following orders.

The melody for the song is a well-known patriotic song, Battle Hymn of the Republic. It was very common for composers to use and re-use melodies and familiar hymns with new text (especially patriotic melodies). By using this melody, the composer immediately evokes feelings of nostalgia and patriotism. It starts with a humble-sounding banjo and military-like snare drum. The song reached #49 on Hot Country Songs, selling over 1 million copies in 4 days-- it currently appears on at least five albums on Spotify.

The text of the song mostly mitigates Calley's actions-- portraying him as a little boy who just wanted to serve his country, never letting go of the flag. The last verse begs, "When all the wars are over and the battle's finally won, count me only as a soldier who never left his gun."

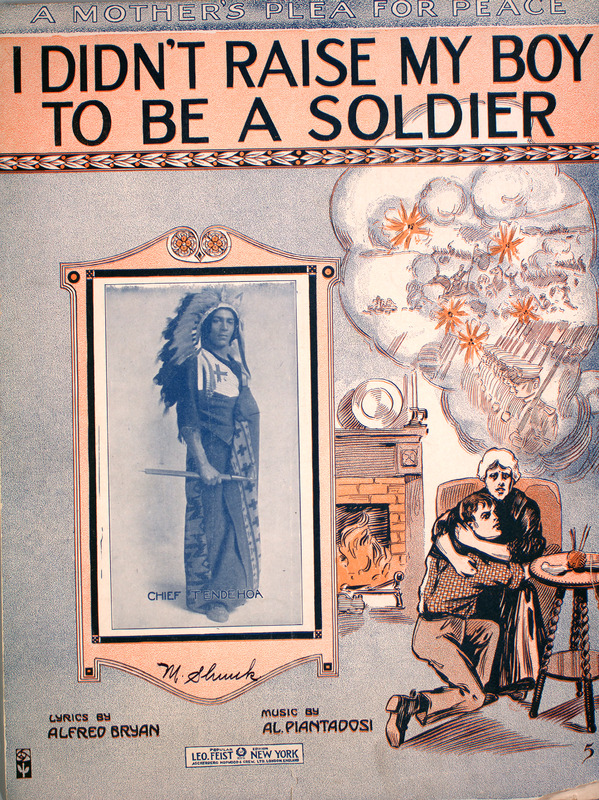

This song was published in New York in 1915, the second year of the first World War. The cover was printed with a blank section so a local celebrity could be inserted-- in this case, "Chief Tendehoa." Conflicting information exists on the identify of this performer-- one source claims this is a White person in Native American clothing. However, period newspaper clippings claim he was a Sioux performer in vaudeville shows.

The imagery on the cover is quite emotional-- we can see a mother and son sitting in front of the fireplace, where the mother appears to have put down her knitting to embrace her son. Both of them are looking directly at us with fear and anger in their eyes. Hovering above them is a cloud of war, with bombs and smoke--- the mother even appears to be positioned so that she's protecting her son from the war.

The song was very popular in its time, reaching #1 in the charts in 1915. It also faced high-level criticism-- Theodore Roosevelt remarked that "Foolish people who applaud a song entitled 'I didn't raise my boy to be a soldier,' are just the people who would also in their hearts applaud a song entitled 'I didn't raise my girl to be a mother." To Roosevelt, it was just as obvious that a boy will become a soldier as a girl will be a mother. The song was parodied often, with people changing the lyrics to "I didn't raise my boy to be a coward," and "I didn't raise my dog to be a sausage."

The text has a number of calls for peace-- one of the most powerful is, "There'd be no war today if mothers all would say, ' I didn't raise my boy to be a soldier.'"

This Civil War-era ballad was reportedly sung by soldiers from both the Union and Confederacy. There are even reports of enemy troops camped near each other singing the song together across battle lines—the song was eventually banned by the Union for fear that homesick soldiers might abandon the army.

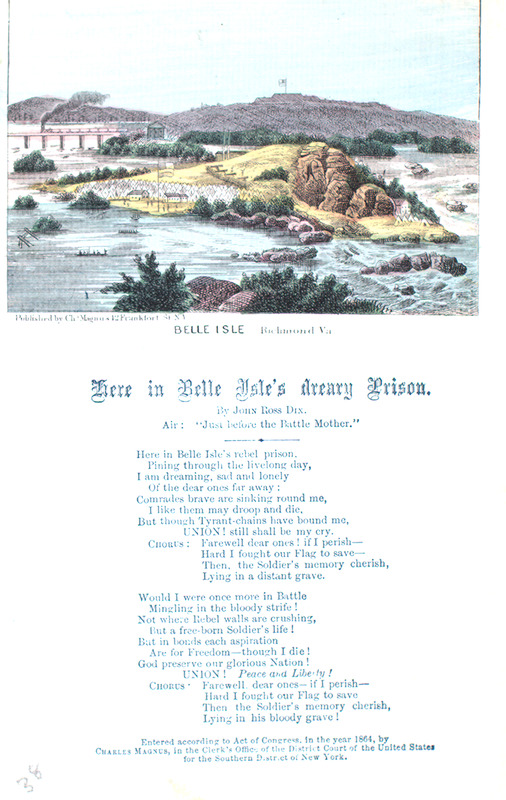

John Ross Dix was a British composer who wrote numerous songs in support of the Union. This object is published in the form of a song sheet, with the well-known tune listed as an ‘air’ below the title. Belle Isle was a prisoner-of-war camp for Union soldiers, known for its particularly harsh conditions.

This is the earliest dated song in the Levy Collection, published in London 1779. The song seems to be a response to the Revolutionary War, as the lyrics repeat “we must be good subjects” as if lines on a schoolroom chalkboard.

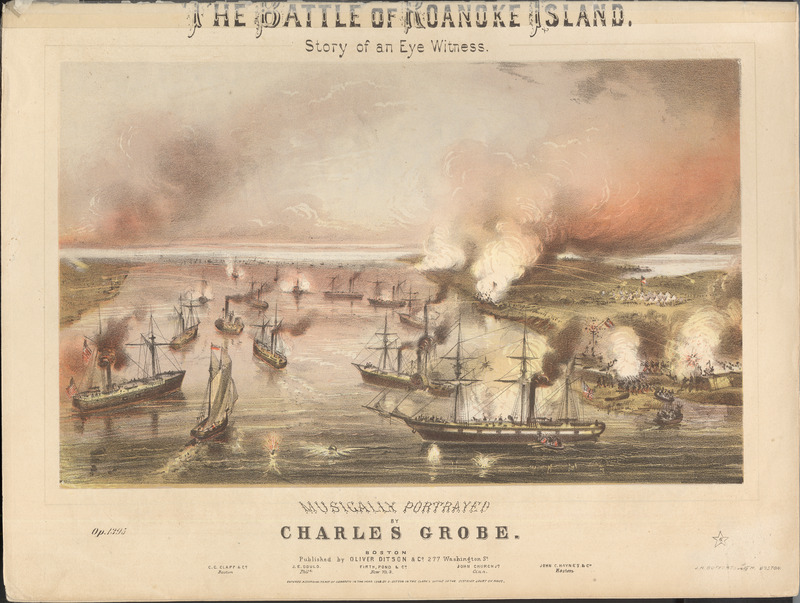

This Civil War era song is an example of programmatic music—music meant to replicate or represent real-world events. The melodies depict different aspects of the Battle of Roanoke in 1862.