Under the auspices of Hopkins Retrospective and through the Sheridan Libraries, this archive explores and publicly presents archival evidence related to the life of Johns Hopkins and his family.

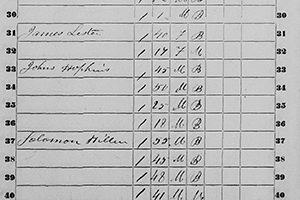

In a message on December 9, 2020, Johns Hopkins University and Medicine leadership shared with the Hopkins community new insights into our founder, Johns Hopkins. This included the discovery of a government census record that listed him as the owner of four enslaved people in 1850. Additionally, the 1840 census reported one enslaved person as living in Johns Hopkins’ household, though that form did not designate ownership. His 1860 census record listed no enslaved people in his home. These records and other documents linking Johns Hopkins and his family to the institution of slavery challenge the previously accepted story of Johns as an early and staunch abolitionist, which was drawn largely from a book of reminiscences written by his grand-niece, Helen Thom, and originally published in 1929.

Today, Johns Hopkins University historians, archivists, and students are continuing to delve into this history. Through this bibliographic archive Hopkins Retrospective will share additional records with the public as they become available. We strive to illuminate all aspects of our founder’s life and to share a more complete and truthful narrative. This site is a work in progress and will continue to be updated with new documentation.

Johns Hopkins, a reexamination

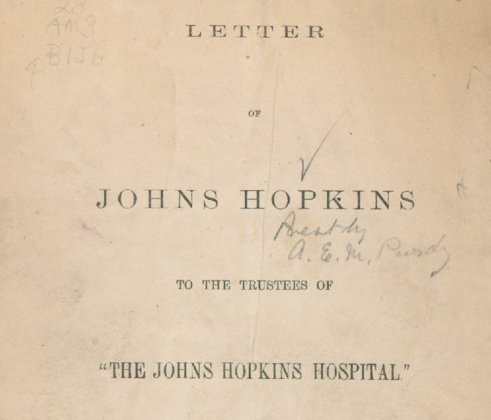

The evidentiary record of archival materials relating to the life of Johns Hopkins is thin. For years, leaders and community members rooted the story of our founder in the terms of his benevolent gift to the city of Baltimore: a university and a hospital, and a general claim that he was an abolitionist. His will and letter to the hospital trustees contextualize this philanthropic bequest, including his direction that his trustees establish a hospital to serve the indigent of Baltimore regardless of race, sex or age, and that they found an orphanage for the care and education of Black children in Baltimore. Our previous narrative also relied on an account by Hopkins family member Helen Thom that described Johns' Quaker parents as having manumitted those they held enslaved in 1807. This aspect of Thom’s narrative cannot be substantiated. No extant manumission records in Maryland show Johns Hopkins’ parents, Hannah and Samuel, freeing enslaved individuals. Records do show that Johns’ grandfather, Johns Hopkins the elder, manumitted nine enslaved individuals in 1778, while also converting others, many of them children, to term slaves.

Historians have discovered only a few documents written in Johns Hopkins’ hand. No comprehensive biography of him exists, though parts of his life are included in works on Baltimore’s history.i His personal papers were likely lost or destroyed. The archival record assembled so far suggests that Johns Hopkins was a complex person – a businessman and philanthropist whose bequest transformed higher education and healthcare in America, and a civic leader who participated in a world that relied heavily on the institution of slavery and who was listed in a government record as a slave owner. Johns was raised as a Quaker and at the end of his life was reported by some to have held anti-slavery views. This site outlines Johns Hopkins’ life thematically, referencing archival documents that illuminate his life. This narrative is a work in progress and will be updated as new records are unearthed, consulted, and shared.

Johns Hopkins, our founder

Portrait of Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins, son, Quaker

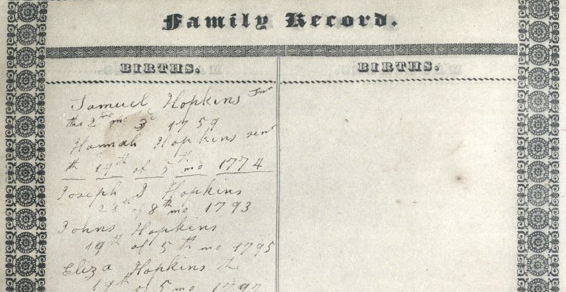

Johns Hopkins was born in 1795, the second of 11 children of Samuel and Hannah (Janney) Hopkins, Quakers who owned a tobacco farm called White’s Hall in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.iv When he was 17 years old, Johns left his parents' plantation and moved to Baltimore where he worked for his uncle Gerard T. Hopkins in the wholesale grocery business. Within a few years, he established himself as a savvy businessperson and ultimately entered a partnership with his brothers, Mahlon, Philip, and Gerard, forming “Hopkins & Brothers Wholesalers.”v While living with his uncle and aunt, Johns developed a deep affection for his cousin, Elizabeth, to whom he would leave his home when he died.vi Initially following in his parents’ footsteps, he was a member of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, at the Baltimore Monthly Meeting for the Western District. After being warned, Johns and his brother Mahlon were disowned or expelled from the Society of Friends in 1826 for “the practice of trading in distilled spiritous liquors.”vii

There is no evidence that Johns Hopkins rejoined the Society of Friends. Still, in later years, he contributed toward construction costs of a new Quaker meetinghouse at the corner of Eutaw and Monument streets.

Johns Hopkins, brother, businessperson

Johns Hopkins led a successful life in Baltimore, but he was no stranger to illnesses like cholera and yellow fever that plagued cities during the nineteenth century; three of his brothers died before him in quick succession: Gerard in 1835, Mahlon in 1840, and Philip in 1843. One letter survives that illuminates Johns’ feelings after Mahlon’s passing. He wrote to his mother, Hannah: “I have led a life of great devotion to worldly pursuits – but in the death of my endeared brother Mahlon a total change has been brought about in my feelings.”viii Sometime after 1840, his mother moved to Baltimore to live with Johns. His sisters, Hannah and Elizabeth, also moved into Johns’ home at 177 Lombard Street.ix

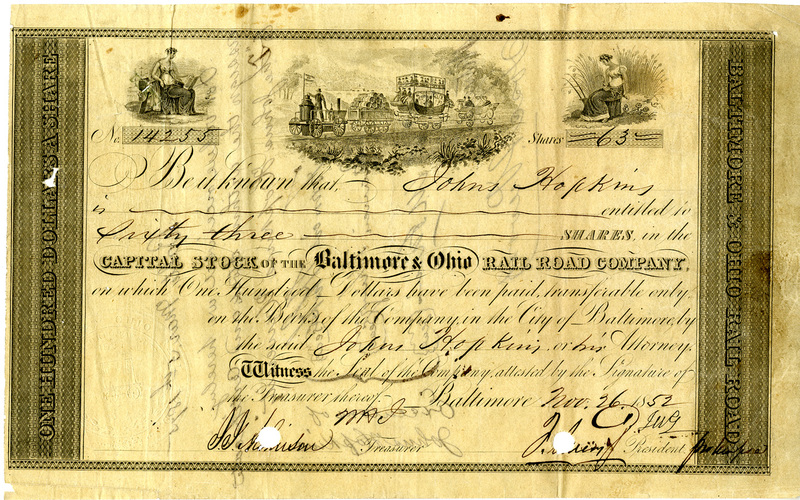

Johns moved on from the grocery business and pursued a career as a financier and investor. He served as president of the Merchants’ Bank, and he was chairman of the Finance Committee of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.x One of the company’s largest shareholders, he assisted the B&O during financial crises and developed a friendship with the longstanding president, John Work Garrett.xi The men maintained this bond as they confronted the impacts of the Civil War on Baltimore, and when they mobilized the railroad to support President Lincoln and the Union.

While Civil War sympathies were divided in Baltimore, Johns Hopkins supported the Union. In September 1863 President Lincoln’s Secretary of Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, traveled to Baltimore. He reflected in his diary about on walking the grounds of Clifton and dining with Johns Hopkins. Chase wrote, “The guests were intelligent and substantial men, consisting, as Mr. Hopkins said, the best part of the Baltimore merchants and capitalists. And all of them earnest Union men. And nearly all, if not all, decided Emancipationists.”xii Later, one obituary in the Baltimore Commercial and Advertiser also noted Johns’ support for the Union: “We shall only allude to the late civil war to say that Mr. Hopkins was a firm supporter of the Government. In founding the charitable institution with which his name is inseparably connected, he took pains to have the charters framed in accordance with his humane and liberal views concerning the common brotherhood of man. There can be no discrimination on account of color in the Johns Hopkins Hospital.”xiii

Johns Hopkins, philanthropist

In 1867, Johns Hopkins turned his attention to his final contributions to the city of Baltimore. He made what was at the time the single largest philanthropic bequest to an American educational institution, which, with the trustees’ help and the leadership of Daniel Coit Gilman, launched America’s first research university. When Johns died in 1873, a writer in The Baltimore Sun reflected, “Baltimore loses not only its most prominent business man but a public benefactor.”xiv

Johns Hopkins’ bequest included explicit direction for his trustees to establish a hospital for the public, one that would treat the indigent sick of Baltimore.xv He also advocated for and provided funds for a training school for female nurses that would serve in the hospital wards. Johns made provisions in his will for the development of the Johns Hopkins Colored Orphan Asylum and as described in the document, he hoped this effort would focus on the “maintenance and education of orphan colored children,” ones that were “in such circumstances as to require the aid of the Charity.”xvi In his will, he indicated that the facilities should be segregated by race, writing that the asylum should be “built at a distance from, the wards, or buildings intended for sick poor white persons, or of sick poor colored persons.”xvii Research into the segregation of the hospital and on the trajectory of the asylum is ongoing.

One account of the community’s reaction to his work, an article from The Baltimore Sun in April, 1873 headlined “The Johns Hopkins Charity,” described a gathering of Black civic leaders (local Baltimoreans and others) at the Douglass Institute.xviii As reported, the speeches from the event include references to Johns Hopkins’ philanthropy and support for Black Baltimoreans. Further research is needed to place this report in context of other contemporaneous views of Johns Hopkins.

Johns’ philanthropy also had a personal element; in his last moments, he took care in his will to provide for many of his family members and for the servants who lived and worked in his household: James, Chloe, and Charles.xix Specifically, he left James a home on French Street and $5,000. He bequeathed $1,000 to Chloe and $2,000 to Charles.

Johns Hopkins, his family, and the coexistence of slavery and freedom

The Hopkins family – beyond Johns, the founder – dealt in slaveholding and manumission in its earliest generations. Johns Hopkins, the elder (Johns’ grandfather), manumitted, or set free nine enslaved people in 1778 as recorded in Anne Arundel County land records.xx At the same time, Johns the elder made 33 other enslaved young adults and children term slaves who would remain enslaved until the ages of 21 for girls and 25 for boys. Pressure from the Society of Friends may have influenced this decision.xxi Additionally, when Johns Hopkins the elder died, he still held 14 enslaved people whom he bequeathed to his children through his last will and testament.xxii One of these enslaved individuals, a boy named John, was given to Samuel Hopkins, Johns Hopkins the founder’s father. If Samuel followed the terms of his father’s will, this enslaved boy, who was born in 1771, would have become free only in 1796. Court records from Anne Arundel County confirm that one of the enslaved women, Affy, received a certificate of freedom in 1814 , in that record she was listed as about “thirty eight years of age.”xxiii This record shows that her manumission was carried out legally and she had been living as a free woman since the age of 21.

The Hopkins family relied on more than one form of unfree labor. In 1807, Samuel Hopkins entered into an indenture contract with a free Black woman named Phillis, binding her sons, Jeremiah, 10, and Thomas, 7, to Hopkins until they reached the age of 21. These boys were to learn the “art of planting” from Samuel, and when they became free, they would earn a “suit of clothes.”xxiv

After Samuel’s death, Johns’ mother Hannah and his older brother Joseph J. Hopkins entered into an indenture contract in 1821 with an unnamed mother in order to teach the “art of planting” to her 5 children (Henry, John, Arch, William, and Lydia) who were all between the ages of 7 and 11.xxv This record furthers our understanding of how the Hopkins’ family tobacco plantation, White’s Hall, operated despite the gradual absence of enslaved men and women.

Slavery and freedom coexisted for years within different parts of the Hopkins family. Joseph J. Hopkins issued a deed of manumission in 1832 after being paid $100 for the freedom of two enslaved women, Minta (sometimes referred to in records as Minty) and Louisa (sometimes with the last name Wells or Wills).xxvi This act of emancipation is confirmed by the certificates of freedom issued to Minta and Louisa from the Anne Arundel County Court; these records are legal documents that verified a free Black person’s status in the state of Maryland.xxvii

Federal census records list one enslaved person in Johns Hopkins’ household in 1840; the record in that year also counts two free Black individuals. In 1850, the slave schedule portion of the census lists four enslaved people in his household: men aged 50, 45, 25, and 18 years.xxviii Research conducted in 2020 by Professor Martha Jones and Hopkins Retrospective confirmed that these records refer to Johns Hopkins, our founder.

The 1850 document lists Johns Hopkins as the owner of the four men. For purposes of that year’s census, the term “owner” was defined as any person who held enslaved people in their household, whether that head of household owned, rented, borrowed, or otherwise exercised dominion over the enslaved person.

Johns Hopkins’ brother Samuel and his wife Lavinia also held enslaved people in their household. In 1850 the census taker reported two enslaved women, aged 14 and 80, in their household. In 1860, their household included one enslaved man, aged 20 years, who was recorded as being owned by Lavinia. xxix In 1860, Samuel and Lavinia’s household also included two servants, Henry Robbins (60) and James Snowden (35), who were listed as “Mulatto” and “Black,” respectively.xxx

Baltimore County tax records from 1841 show that Johns Hopkins was taxed for his property at Clifton (166 acres), horses, and cows.xxxi He was not taxed for owning enslaved people in this record, nor was his grocer business, Hopkins & Brothers, taxed for ownership of enslaved people in 1842.xxxii Johns’ neighbors and other nearby businesses were taxed for enslaved people during these years.

Other archival documents provide additional clues about Johns Hopkins’ relationship with the institution of slavery. In 1831, in connection with the Hopkins Brothers enterprise, brothers Johns and Mahlon looked to take possession of an enslaved person from one of their debtors, the Keech family.xxxiii As detailed in a letter from the Hopkins Brothers to William B. Stone in 1838, the brothers’ firm agreed to accept an enslaved person as collateral for a debt.xxxiv

By 1860, there were no enslaved people listed in Johns’ household. That year’s census return includes three Black servants living in his household: James Jones (coachman), Henry Rough (waiter), and Clark Brown (servant).xxxv The 1870 census record reported that his household included his sister Hannah, as well as three individuals: James Jones and Charles Tolbert, both waiters, and Chloe Johnson, a domestic servant.xxxvi

Later reports looked back at Johns Hopkins’ household in the years before slavery’s abolition. A 1873 Baltimore Sun obituary entitled “The Late Johns Hopkins” explained: “Three colored servants, who had lived with Mr. Hopkins for many years, it is understood, are duly remembered in his will…The man James was once the slave of Mr. Hopkins, he having purchased him of a Mr. Tayloe in Virginia, at whose house he observed such qualities in the then colored youth as induced him to bring him to Baltimore, where subsequently he gave him his freedom years ago.”xxxvii

A Baltimore American newspaper article in that same year stated that Hopkins “purchased a slave to make him free” and goes on to explain that the unnamed man worked for him until Hopkins died.xxxviii Within Johns Hopkins’ will he provided money and a house for his “servant man,” James. His age is consistent with that of one of the four enslaved individuals listed as owned by Johns Hopkins in the 1850 slave schedule, but it is not known whether it is the same person.

Hopkins Retrospective continues to interrogate and identify additional records that will tell a fuller story about Johns Hopkins and the enslaved people in his household, and we seek to piece together archival fragments in order to develop a deeper understanding of the Hopkins family’s intergenerational relationship with slavery and Black labor.

Get involved

We are at the beginning of learning more about Johns Hopkins’ life as we develop a deeper, more extensive archival record. We hope that others – our students, faculty, and staff as well as our neighbors in Baltimore – will help contribute to this work of gathering and sharing documents and interpreting them. Please reach out if you know of relevant archival collections!

Feedback

HopRetroRexaminingHistory@jhu.edu

Frequently asked questions

Footnotes

i Authors including Antero Pietila, Matthew A. Crenson, Edward C. Papenfuse, and Kathleen Waters Sander.

ii Johns Hopkins, Last Will and Testament, March 10, 1873, Hopkins Family Collection, MS 0078, Ferdinand Hamburger University Archives, Johns Hopkins University. Also located in Baltimore County, Register of Wills, Estate Papers, 1873-1875, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland. Johns Hopkins, “Letter of Johns Hopkins to the Trustees of the Johns Hopkins Hospital,” March 10, 1873 (Baltimore: Wm. K. Boyle & Son), http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101235227, Accessed December 4, 2020.

iii Johns Hopkins, “Letter of Johns Hopkins to the Trustees of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.”

iv Hopkins Family Bible, Hopkins Family Collection, MS 0078, Ferdinand Hamburger University Archives, Johns Hopkins University. The Whites Hall plantation is also occasionally referred to as White’s Hall and White Hall farm.

v “Hopkins & Brothers,” American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, January 12, 1824.

vi Johns Hopkins, Last Will and Testament, March 10, 1873, Hopkins Family Collection, MS 0078, Ferdinand Hamburger University Archives, Johns Hopkins University.

vii Disownment of Johns and Mahlon Hopkins Quaker Meeting, December 8, 1826. Minutes, 1824 -1848, Collection: Baltimore Yearly Meeting Minutes, RG2/B/B353, 1.8, Swarthmore College.

viii Johns Hopkins letter to his mother, Hannah Hopkins, April 25, 1840, Correspondence of Johns Hopkins, Johns Hopkins Collection, The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, https://medicalarchivescatalog.jhmi.edu/jhmi_permalink.html?key=276434, accessed December 16, 2021.

ix Classified Ad 6 -- no Title." The Sun (1837-), Feb 20, 1850. 3, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-6-no-title/docview/533249025/se-2?accountid=10750, accessed December 16, 2021.

x John Stover, History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press), 1984.

xi Kathleen Waters Sander, John W. Garrett and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, (Baltimore: JHU University Press), 2017.

xii The Salmon P. Chase Papers, Volume 1, Journals, 1829-1872, John Niven, Editor, James P. McClure, Senior Associate Editor, Leigh Johnsen, Associate Editor’ William M. Ferraro, Assistant Editor, Steve Leikin, Assistant Editor, The Kent State University Press, 1993, p. 455.

xiii Editorial Column about Johns Hopkins, “Death of a Useful Man,” December 25, 1873, The Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser. (Accessed on Google newspapers).

xiv “Death of Mr. Johns Hopkins,” The Baltimore Sun, December 25, 1873.

xv Johns Hopkins, “Letter of Johns Hopkins to the Trustees of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.”

xvi Johns Hopkins, “Letter of Johns Hopkins to the Trustees of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.” See also retired Maryland State Archivist Dr. Ed Papenfuse’s work on the Johns Hopkins Colored Orphan’s Asylum, “Whatever Happened to Birdie Shine?: Caring for the Children At The Johns Hopkins Colored Orphan Asylum, and its predecessors, 1867-1923.” http://www.rememberingbaltimore.net/2020/12/whatever-happened-to-birdie-shine.html

xvii Johns Hopkins, Last Will and Testament, March 10, 1873.

xviii “THE JOHNS HOPKINS CHARITY: Enthusiastic Mass Meeting of Colored Citizens -- Resolutions and Speeches,” April 9, 1873, The Baltimore Sun.

xix Johns Hopkins, Last Will and Testament, March 10, 1873.

xx Johns Hopkins Sr., Manumission, August 7, 1783, Anne Arundel County, Land Records, Liber I.B., No. 5, Folio 537-539.

xxi “West River Monthly Meeting,” Friends’ Intelligencer, October 28, 1893. “Journal of Margaret Cook,” Friends’ Intelligencer and Journal, May 29, 1897.

xxii Johns Hopkins Sr, Last Will and Testament, July 30, 1784, Anne Arundel County, Register of Wills, Book E.V., No. 1, Folio 194-196.

xxiii Certificate of Freedom for Affy, June 8, 1814, Anne Arundel County, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1831, CM789-3, p. 43-44. Readers can access information about Certificates of Freedom and Manumissions through the Maryland State Archives; this guide explains what these records are, what information they contain, and for what counties they are still extant. Additionally, you can access the publication "Researching African American Families" at the Maryland State Archives.

xxiv “Indenture for Jeremiah and Thomas” Phillis to Samuel Hopkins; Indenture (for children Thomas and Jeremiah), November 16, 1807; Hopkins Family Collection, MS 0078, Special Collections, The Johns Hopkins University.

xxv Indenture Contract to Joseph J. Hopkins and Hannah Hopkins, August 11, 1821, (for children Henry, 11, John, 10, Arch, 10, William, 9, and Lydia, 7), Anne Arundel County, Indentures, Original, 1795-1820, CM1358-1, T.H.H. No. 1, folio 207, (p.325 in scan).

xxvi Deed of Manumission for Minta and Louisa Wells, May 25, 1832, Anne Arundel County Court, Manumission Records, 1816-1844.

xxvii Certificate of Freedom for Louisa Wills, October 23, 1838, Anne Arundel County, Certificates of Freedom, 1806-1851, C46-4, p. 276-277. Certificate of Freedom for Minta, May 28, 1832, Anne Arundel County, Certificates of Freedom, 1806-1851, C46-4, p. 129-130.

xxviii Ellridge G. Hall, Assistant Marshal; 2nd Enumeration District, Baltimore County, Maryland Census of Slaves; August 14, 1850, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, National Archives and Record Administration. Ward 9, Baltimore County, Maryland Census of Population, 1840, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840, National Archives and Record Administration. Update, 03/25/2021: For more information on how the U.S. Census was taken in these years, please see the United States Census Bureau, Decennial Census Technical Documentation, “1850 Census Instructions to Enumerators,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires/1850/1850-instructions.html

xxix George C. McGee, Assistant Marshal, Ward 11, Baltimore County, Maryland Census of Population, 1850; Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, National Archives and Record Administration. George H. McGee, Assistant Marshal, Ward 11 Baltimore City, Baltimore, County, Maryland, Census of Slave Inhabitants 1850, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, National Archives and Record Administration. C.C. Dunn, Assistant Marshal, Ward 11, Baltimore County, Maryland Census of Population, 1860; Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, National Archives and Record Administration. C.C. Dunn, Assistant Marshal, Ward 11, Baltimore City, Baltimore County, June 5, 1860, Census of Slave Inhabitants, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, National Archives and Record Administration.

xxx C.C. Dunn, Assistant Marshal, Ward 11, Baltimore County, Maryland Census of Population; 1860; Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. National Archives and Record Administration.

xxxi Tax record for Johns Hopkins, 1841, Baltimore County, Board of County Commissioners (Assessors Field Book), 1833-1858, C281-11.

xxxii Tax record for Hopkins & Brothers, 1842, Baltimore City, Baltimore City Archives (Baltimore City Property Tax Records), 1842, Book Name 4, BCA 160-2, BRG4-1-68.

xxxiii William L. Keech v. Johns Hopkins & Mahlon Hopkins, PAR 20982601 and PAR 20983106, Race & Slavery Petitions Project, UNC Greensboro.

xxxiv Hopkins Brothers to William B. Stone, March 13, 1838, The Gilder Lehrman Collection, 1493-1859, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

xxxv Entry for Johns Hopkins, John S. Hayes, Assistant Marshal, 12th Enumeration District, Baltimore City, Maryland Census of Population, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, National Archives and Record Administration.

xxxvi Entry for Johns Hopkins, Wm. Blackistone (sic), Assistant Marshal, 12th Enumeration District, Baltimore City, Maryland Census of Population, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870, National Archives and Record Administration.

xxxvii “The Late Johns Hopkins,” The Baltimore Sun, December 27, 1873.

xxxviii Editorial Column about Johns Hopkins, “Death of a Useful Man,” December 25, 1873, The Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser. (Accessed on Google newspapers).

1850 Census Slave Schedule Record for Johns Hopkins

1850 Census Slave Schedule Record for Johns Hopkins