-

Immigrants of Hopkins 18

Immigrants of Hopkins 18

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 17

Immigrants of Hopkins 17

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 16

Immigrants of Hopkins 16

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 15

Immigrants of Hopkins 15

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 13

Immigrants of Hopkins 13

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 12

Immigrants of Hopkins 12

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 11

Immigrants of Hopkins 11

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 10

Immigrants of Hopkins 10

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 9

Immigrants of Hopkins 9

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 8

Immigrants of Hopkins 8

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 7

Immigrants of Hopkins 7

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 6

Immigrants of Hopkins 6

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 5

Immigrants of Hopkins 5

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 4

Immigrants of Hopkins 4

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 3

Immigrants of Hopkins 3

-

Immigrants of Hopkins 2

Immigrants of Hopkins 2

-

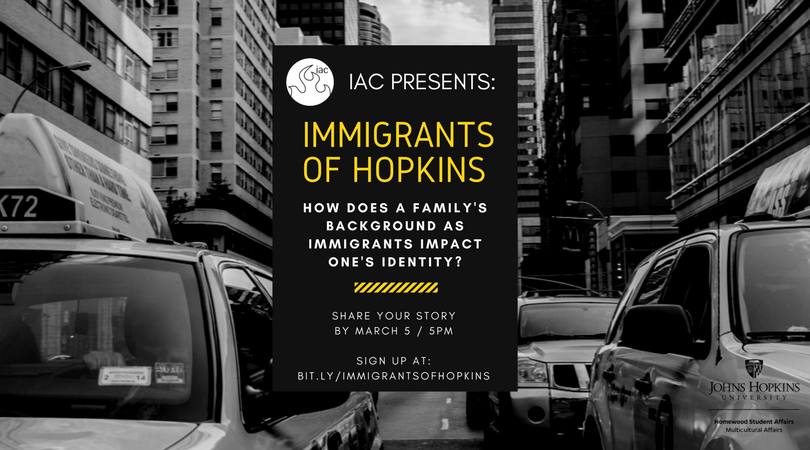

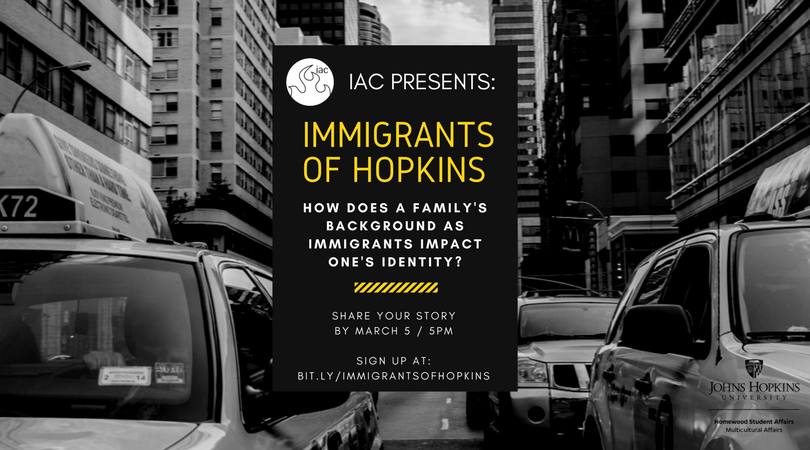

Immigrants of Hopkins Event 1

Immigrants of Hopkins Event 1

-

Shawn Gunaratne

Shawn Gunaratne How does being an immigrant affect your identity?

“I can’t even imagine not being an immigrant; it influences my entire perspective. The seminal point, I would say, is post-9/11. Being a brown man in America was very different pre-9/11. I was in high school when 9/11 happened, and you were immediately looked at differently.”

Since 9/11 in 2001 to now in 2018, what do you think has changed?

“I don’t know if much has changed; my perspective on the world is based on being a minority American. So being a person of color is a huge part of how I approach the world. Whenever there’s any type of attack or shooting in this country, my first thought is whether or not it’s a brown guy.”

Why do you think your first thought is “don’t let it be a brown guy”?

“Especially being in Orange County, which is the most conservative part of California, I’m always conscious of how people look at me, and how I represent myself. If something bad happens in our country and it is a ‘brown person,’ then many people’s first thoughts are, ‘They must all be like that.’ But if it is a white person, then for some reason it is considered to be an outlier.

I’ve also had experiences where I’ve been kicked out of bars because people didn’t like the color of my skin. But at the same time, similar to what Obama said in 2004, in no other country is my story even possible. I think you can come to this country and in one generation ‘make it’ and I think my parents are perfect examples of that.”

- Shawn Gunaratne

-

Sofia Ahsanuddin

Sofia Ahsanuddin So what’s been the most challenging aspect of living here as an immigrant?

“I think the most challenging aspect is always feeling like you have to do more to prove yourself and to prove to people that there’s a reason why you’re here and that you’re contributing to the society just like everyone else is. I think that there’s so much increased skepticism and scrutiny of immigrants and Muslims, two of many groups that are not being perceived well. It’s unfortunate that one person, or a group of people, have such a monopoly on the way my community is viewed in India and the United States as well.”

Are there any resources you wish you had to make the transition or your time here easier?

“I think I’ve had many blessings and I’ve had many opportunities. I have been given many opportunities throughout my life and I’m very grateful and blessed to have had that. But I think that in terms of facing some of the racism, discrimination, and stereotypes that people have about people from my faith, it can be challenging if they’re not prepared to deal with that. Since I’m based in NYC and I’ve lived my whole life in NYC, I grew very much accustomed to living in an environment that constantly exposes me to different world views, cultures, and backgrounds, which was very good for me. If I could change one thing about my upbringing, in terms of support, it would have been access to role models who were Muslim women. Women who were older immigrants and went through the same things that I went through, and who could coach me through that, because I had to learn things on my own and learn how to deal with these challenges on my own. If I had access to a support network of older people who went through these challenges and knew how to navigate the system, that would’ve been more beneficial.”

- Sofia Ahsanuddin

-

Mayriam Robles Garcia

Mayriam Robles Garcia Can you tell me a little bit about yourself?

“My name is Mayriam Alejandra Robles Garcia. I am a physician who is currently a 2nd year MPH/MBA student at Bloomberg and Carey. I was born and raised in the U.S. until age 10 and then finished growing up in the Dominican Republic, where my parents are from. I am very proud of my ethnicity and culture and never deny where I am from because I think it makes me diverse, which is a good thing. I can very easily adapt to other cultures and respect people’s beliefs. I have a genuine interest in people and think difference is what brings change and unity. Professionally, I am passionate about patient safety, healthcare initiatives focused on minorities, and overall, reaching better practices in medicine. This project was important to me as inclusion is necessary, but for this to happen people must be outspoken to attract others to engage.”

Can you talk about your experiences as an immigrant or having an immigrant background?

“Yeah, I consider myself from the Dominican Republic. It was definitely a cultural shock when I came here. You might say, ‘Yeah, but you were in the U.S. for some time prior to coming to Hopkins,’ but Miami is very very Latino, which is what I’m used to. Everyone in each store speaks Spanish. So you feel like, you know, you’re in a Latin American country. Coming to Hopkins, it was really difficult because there are so many brilliant people here that you would feel intimidated. So at Bloomberg, there is almost no diversity in terms of Latinos. There are a lot of Indians, Asians, Americans, Africans, but a very small percentage of Latin-Americans. So yeah, it was difficult in a way. People were friendly, so I’m glad I haven’t encountered anything negative in that aspect. But I would say when you go out, there are some places, not necessarily here at Hopkins, where you feel like you don’t fit in...It’s really difficult, because when you come here and you feel that you’re discriminated or put aside, you can become super depressed. You don’t do well in school. You might even think of suicide or you just want to go home and say this isn’t the place for you. That’s why a lot of people drop out and change schools.”

- Mayriam Robles Garcia

-

Carolina Andrada

Carolina Andrada What resources did you wish you had having newly immigrated to the United States?

“I wish I just knew other immigrants. I grew up in an area where I knew no one else. I was coming from a different place. The Argentine community was me, my sister, my parents, and a few old couples. That was it. And there weren’t too many families from Central America and South America, so it wasn’t like I could speak Spanish with anybody. I think that something really important is keeping in touch with your culture, but also being able to interact with other people that have been assimilating to the new culture as well, and finding ways to integrate yourself within the new culture while retaining your old culture. I feel that’s a really big issue when you are in rural areas like I was. Some kind of mentorship and cultural connection would have been nice.”

What is your best memory about your family’s immigration story?

"So my dad came over and he was here for a year. When we finally moved over, we flew into Tallahassee. I was six, my sister was one, and we’d only been to the U.S. once before. I had been once before to vacation in New York, but I was a toddler then. Another time, my parents had been to New Orleans or something. But, for some reason, we had never seen squirrels. We got out of the tiny little Tallahassee International Airport, and we were just walking around - it was Valentine's Day and it was chilly outside - and then I was like, ‘What is that?’ Squirrels do not exist in Argentina. There is no such thing as a squirrel. My mom had never seen a squirrel and my mom said, ‘It’s so small. It’s like a chipmunk.’ We had also never seen chipmunks. My whole family just started chasing after the squirrels, the four of us, with all of our luggages - two grown adults with a baby in arms, and their six year old screaming at the top of her lungs. That was the happiest freaking moment of that entire trip, after all of those flights.”

- Carolina Andrada

-

Nikki Garcia

Nikki Garcia What was the hardest thing that your family encountered as immigrants coming to the United States?

“When my parents first came here, they told me stories about the holidays. They didn't really understand the holidays, specifically Thanksgiving. They told me that they were at a restaurant on Thanksgiving and the restaurant was empty and the waiter was treating them a little weird. They didn't understand why until they talked to my uncle who had been in the States for some time. He explained that it was a very serious family holiday where everyone got together and usually people spend it at their houses.

My parents didn’t really go out. It was really uncomfortable for them, I think. My parents both speak Spanish, and in Miami, everyone speaks Spanish or it feels like everyone speaks Spanish, so it's not so much that the language is a barrier, but it becomes harder to learn English. My dad studied for some years in Canada, so he knows how to speak English well, but my mom, to this day, has a heavier accent than my dad.

Back then, my mom didn't speak English at all, but what she ended up doing was teaching QuickBooks, which is a financial software. And she taught it in English. She learned how to communicate better in English and even though she still has her accent, she can communicate a lot better than she could back then. So language was a barrier in the sense that it was harder to learn English.

- Nikki Garcia

-

Kelvin Qian

Kelvin Qian What are you fond of about of your culture?

“Let me tell you a historical piece of trivia. Have you heard of Alberto Santos-Dumont? He was a Brazilian who had French and Portuguese heritage and he’s considered in Brazil to be the inventor of the airplane, which is different from America. So, Santos-Dumont is a name with a hyphen, and when he writes his name he puts an equal sign, because he wants to acknowledge both his European and Brazilian heritage. I kind of feel the same way. I’m proud of being Chinese because looking back in history, we basically invented everything. We invented gunpowder, paper, compasses, seismographs, plows, wheelbarrows, massive engineering projects like the Grand Canals, basically the ‘greatest empire’ in history. I put that in quotes because that’s a loaded term. But I’m also proud of being American. I feel like the 2016 election actually affirmed that American identity because it showed how many Americans believe in the ideas of multiculturalism, diversity, liberalism. These are the kinds of things you don’t see in China - at least not multiculturalism, which might explain why some of these immigrants are racist.”

Yeah, it makes sense. Obviously, America’s population is more diverse, although there are a lot of ethnic minorities in China and their history is really rich.

“Oftentimes I see how these minorities are treated, either as tourist attractions or discriminated against. It’s not like in America. In the United States, you see minorities standing up for themselves both in history and right now, and how Asian-Americans also participated in the civil rights movement.”

- Kelvin Qian

-

Marlen Tagle Rodriguez

Marlen Tagle Rodriguez Have you ever felt that you have been living with a certain stigma attached to you as an immigrant?

“When I was little, people would say, ‘Go back to Mexico where the trash belongs,’ and stuff like that. Back then, as a young child who was insecure, it was easy to accept it. When I think about it now, I feel like there is a stereotype of my people and what we end up doing in this country and what people say about people from Mexico. But I think the way I take it is that I try to fight it - do outreach and talk to other people who are struggling and encourage them. I think there is a lot of progress to be made.”

What motivated you to participate in this initiative?

“Just to share my story. I’m in the BME PhD program and there’s only like one or two Hispanics...maybe three. I know not everyone is willing to push themselves as much as I am, so I wanted to show up and share my story so that other people know that we exist and that you are not alone. And even if you are alone, it’s definitely something you can do and still be part of who you are.”

- Marlen Tagle Rodriguez

-

Brenda Quesada

Brenda Quesada Can you share with us the story behind your immigration to the United States?

“I remember we left Cuba and went up through Mexico and Texas - through that border. I remember when we got through, they separated us - my dad from me, my mom, and my brother. This was in 2003. My dad had to go through his own immigration and they had to ask him questions about legitimacy and things like that. My brother and I were in a hotel room and I just remember being excited like ‘We’re in a hotel room - awesome!’ But my mom was in tears, because she didn’t know what was going on. She didn’t know if we were going to be sent back. My brother, who’s seven years older than me, was consoling her. At the time, I didn’t know what was going on and was just asking, ‘Where’s dad?’ And my mom was like, ‘Don’t ask that.’ It was very difficult because my mom still hasn’t learned English and I don’t think she wants to. We live in Miami where almost everyone knows Spanish, so everyone communicates just fine. My dad has learned English but he still has an accent. It’s kind of hard because he has a job and he helps doctors input things electronically. But he still struggles a bit to speak English well enough for his colleagues to respect him. Because when you have an accent, you’re looked down upon even though he’s probably smarter than a lot of them. Just because he has an accent and can’t communicate as well, doesn’t mean he doesn’t have the intellect to do so.”

Since coming to Hopkins, have you encountered anything directed towards immigrants that you feel is a misconception or something you want to clear up?

“There is a stigma that immigrants come from lazy families or families that don’t want to do work. Being an immigrant does give you an identity complex, because we struggle with whether we are worth the sacrifice that our parents made for us. It’s so difficult to traverse that for me sometimes, because I have friends who say I’m as American as they are and that they give me worth to be here. It really isn’t your place to say that - I know that I’m worth being here. It’s that assumption that I’m not worth it until someone tells me I’m worth being here."

- Brenda Quesada

-

Emmanuel Opati

Emmanuel Opati Is there anything clashing between your personalities culturally? You being from Uganda and her [your wife] being from America?

“No.”

So it all works out?

“There are different ways of doing things. But not really clashing. Like, do you want your butter in the refrigerator or do you want it out?”

In the refrigerator of course.

“Why? If you're going to use it on bread, it's much better soft outside, than it is in the refrigerator.”

So that it doesn't go bad as fast right?

“It doesn't.”

It doesn't?

“Yeah, so there are different ways of doing things. It's about the intent of the use. If you're going to use it for bread, it's a much easier way of just putting butter on bread when it's soft than when it's hard and you have to wait for it to thaw. It's just more efficient. But yes, marrying someone from a different culture - it does make you question your fundamental beliefs you were raised with, that you took for granted. You have to compromise - life is full of compromises. But you have to be open to questioning your core beliefs. One of my core beliefs was that if I got rained on, I would get sick. My mom kept telling me that, and I was a child. It doesn't have to scientifically make sense. Now I'm old, and if someone tells me that, I question it.”

Do you still feel a disconnect sometimes? Between you and everyone else here?

“Not necessarily as much. I mean, I still do, I still do. I still hold onto the people who want you to change everything, change the way you speak, the way you look. I mean, you can't lose yourself and be someone else. You probably don't like me because of who I am, but I still like myself because of who I am. Now, if I lose this, and I become that, then I would get lost.”

- Emmanuel Opati

-

Natalie Wu

Natalie Wu How would you describe your immigrant background and values?

“My grandpa was actually brought to Taiwan as a refugee during the 1949 revolution. He was one of the first waves to flee there and he basically never saw his family again. But he still has a very positive outlook on life despite everything that’s happened. My mom’s story probably has more impact because she grew up really poor in China during the cultural revolution. She told me about education, because that was the main reason she wanted to come here. She remembered how when they were young, they had to hide and burn any books that were Western books. And she saw my grandpa get sent to re-education for three to four years because he was a high school teacher. So for her, there was a huge focus on education. She was able to get out because she studied really hard and she was one of the top students in the region. She said when the U.S. opened up, they only allowed the cream of the crop to come in. So she knew she had to work her way up there to get to come here. I guess that’s been a big part, just the idea of being able to have a good future with education. I’ve always had really good access to education with tutoring and going to a good public school. My mom had to struggle so much, and wasn’t even able to go to school because of the political stuff happening in China. That has really played a role. And as much as we suffer at Hopkins, it does remind you that there is a reason why you are here and this is a privilege and it’s not something that you should take for granted.”

How would you describe your parents’ process of adapting to the United States?

“I would say my dad embraced it [the United States] immediately. For my mom, it was more of a process over time. There were certain things that drew her over here, like the freedom of speech and assembly, because she was involved with some student protesting in Canton Province before Tiananmen Square happened. That kind of political freedom - she really embraced it. Some other softer cultural things took some more time, and it was definitely a slower process than my dad’s. A lot of it, I think now, has had to do with me and growing up. I was pretty close to her, and from high school onwards, there have been a lot of cultural things and social issues that you normally wouldn’t talk about. Her views have really been impacted by how I view these issues. She’s pretty progressive when it comes to social issues like LGBTQ rights. I think most of my friends are not really comfortable talking about that kind of stuff, but I’m pretty comfortable talking about it with my mom and we have open conversations about that and other social issues. Even things like sexual harassment on college campuses. In the past few years, she has become a lot more Westernized and that has a lot to do with me. I think part of it is that she sees how traditional my best friend’s mom is - they don’t have a really great relationship. They care about each other, but they don’t really talk to each other or have the same type of interactions. And for my mom, I think that’s a big thing - her wanting to understand…to culturally connect. I would say she has still retained certain senses that are traditional, but on certain things, she’s more open to new ideas because she wants to understand me. And because I’ve grown up as an American, she wants to understand what’s going on in my head. She wants to be able to talk about issues, so there’s never anything we

can’t talk about.”

- Natalie Wu

-

Eduardo Sandoval

Eduardo Sandoval Have you ever felt like you were living with a certain stigma associated with your immigrant identity?

“Yes, after I got into college. I went to a high school that was mostly white. When I got into college, a lot of my friends applied to Hopkins and didn’t get in, so they said I only got in because I’m Hispanic and the school wants diversity and everything. So there was a stigma, like, ‘Did I get in because I deserve it?’”

What motivated you to participate in this initiative and what do you hope to gain from or give back to your community by participating?

“I don’t think there’s any representation. There’s just a black box of, ‘Oh, they’re immigrants.’ If you don’t see them directly around you in your community, you stop thinking they’re people with complex lives. So I hope at least one person sees something differently - that’d be nice.”

- Eduardo Sandoval

-

Megan Chen

Megan Chen What is your best memory about your family’s immigration story?

“Funny story - in Shanghai, they have a few fake markets, or markets that sell a bunch of knockoffs of brands. For example, they might have fake Louis Vuitton bags that are intentionally fake. The ‘V’ is oddly shaped because they can’t make it exactly the same. The quality differs between some of them - some stores make them well, some don’t. It’s just really interesting to see. When I was there, I tried to bargain for a lower price. That’s something you have to do, because they’ll want to sell it to you for some amount near the actual price of the bag, which you don’t want. If you want to bargain from $100, start bargaining at $20-25, and you can slowly raise the price, but you want to start low. I was doing that once in 8th grade, and I was speaking in Chinese, but they replied to me in English and they could tell I had an accent. They also charge foreigners more, and I was trying to stay in character. But my Mandarin wasn’t good enough at that point. So my Mandarin was improving, but it was still not there.”

Did you speak Mandarin at home in the United States?

“Actually, it’s interesting. My immediate family is me, my mom, and my dad - no siblings. But when it was just the three of us, I actually spoke Mandarin more than I do now. Because in their current jobs, they are working with lots of people from other places, like France, the UK, and Australia, they speak English a lot and their English also improved. So now it’s a mixture of Mandarin and English. Whereas before, when I was younger, their companies actually had a lot of Asian people. Lots of Asians wanted to work there because of the booming auto industry, so they were speaking Mandarin most of the time, and that carried over to home.”

- Megan Chen

-

Jasmine Du

Jasmine Du How would you say your family’s immigration story has played a role in your life or shaped your identity?

“I never really paid attention to both of my parents’ heritage in that they came here to seek a better life. I didn’t really realize that until I went to community college two years ago. My dad’s story especially shaped my life, because he came here with nothing. When he was my age, he came here to seek a better life. He came here with nothing and the only people he had here were his siblings and maybe some family friends, but he was basically all alone. He taught me to aim high, but at the same time, don’t stress or overexert yourself because you need to make sure you’re healthy. My dad is my biggest role model and I’m very glad he supports me. I don’t think my dad and I really say ‘I love you,’ which is kind of sad. I don’t think a lot of Asian families do either, because we’re not really that affectionate. But I know my dad loves me and I love my dad, and my mom too, of course. But my dad and I have a really strong relationship even though we don’t speak as much. I hope if my dad is reading this, he knows I love him because I haven’t said it that often. Don’t take anything for granted. Really make sure you show how much you love them. I hope my parents both know they mean a lot to me and they’re a big reason why I’m the person I am today.”

- Jasmine Du

-

Colette Aroh

Colette Aroh Have you ever encountered a certain stigma attached to you as an immigrant?

“Hundreds. So growing up, I was at predominantly white institutions, but I was also one of the few black people - we were mostly African. So, a lot of the stereotypes and stigmas I encountered at that time were attached to the fact that I’m Nigerian. And so there are statements like, ‘Did you ride an elephant to school? Your parents have weird food. I called your house and I can’t understand your parents.’ Things like that came up a lot and I associate being different with being Nigerian. Then coming to college and actually meeting other black students from different backgrounds like the Caribbean or other black Americans, there are some core experiences that we shared and that kind of crosses any culture. Like people touching our hair or having ignorant questions and certain stereotypes about black people in general. That would come up too.”

Are there any common misconceptions that people have of you because of your status as an immigrant?

“Yeah, especially the immigration conversation now and being in college and being armed with the first-hand knowledge of how long it took for us to get here. I know it took 15 years to get my grandma here. I’m very aware that the immigration system is very broken. I’ve also encountered other immigrants who had even worse immigration stories and I’ve met refugees - that’s a whole different story about how to receive sanctuary in a country. It frustrates me. I’m actually in an immigration class now and so much of what we talk about in that class is just a lack of knowledge and the ignorance people have. Ignorance itself isn’t bad because it’s just the lack of knowledge, but it’s what we do with that ignorance - whether you speak out of ignorance or you prefer not to gain the knowledge that will take you out of ignorance.”

- Colette Aroh

-

Tracy Gao

Tracy Gao What are some things that we can do as Hopkins students? What do you think would be helpful?

“I think that a really big fault of our community is the lack of conversation. There's a lack of understanding from our generation to our parents' generation and there are just a lot of areas in our community that are not as supportive as they should be. I think that opening up dialogue and being bold enough to share your story is a way that we can build a more understanding and supportive community. So in talking about first-generation Asian Americans in general, we're in a very different position, right? Our parents immigrated to America — they went through so much for us. We can be appreciative, but we just can't fully understand the difficulties they faced. And in the same way, they don't understand what it's like to be caught in this ‘in-between’ in America, being too Asian to be American, too American to be Asian. We’re trying to make space for dialogue and support when there isn't one — when there is no space being given to us. I think that our generation has the power to create the space for ourselves.”

- Tracy Gao

-

Arshdeep Kaur

Arshdeep Kaur How has your family’s immigration story played a role in your identity?

“Cultural differences for sure. I think growing up as a first generation immigrant, there are gaps you notice in your parent’s knowledge of America or Western culture that have been hard to acknowledge sometimes. I used to correct my parents’ English all the time and I’m like, ‘Wait, maybe I should respect the fact that they can speak English and that they’re here in this society, rather than correct the gaps in their knowledge.’”

Do you know how your parents overcame the difficulties they faced as new immigrants?

"I think a lot of it was through faith. So, we’re Sikh. And so faith was very important for all of my family members and that was their link back to where they were from. They rooted their identity in that faith rather than in nationality or in the country where they were living. And family for sure. Even if their family was right next to them at the time, knowing they had the family support was really important.”

What do you think we can do to bridge that gap or change the current view on immigration?

“I think it might be a little bit cliché, but I’ve always found that telling stories is really important. Because I’ve felt that what made me understand people is talking to them and connecting with them. I think that’s important for unity between immigrant groups also. For example, a lot of people don’t realize that a lot of Asian Americans are undocumented. There’s unity to be found there. It’s really upsetting seeing families separated in the current climate. Thankfully, none of my family members have been deported, even though some of them were undocumented. I did have an uncle that was almost deported a few years ago; he was detained for several months. We’re very grateful that didn’t happen. I really think that if our country is deporting people and separating families it casts a very bad light. It doesn’t respect the sacrifices and the strengths that immigrants bring to our country.”

- Arshdeep Kaur

-

Andrew Soonmyung Hwang

Andrew Soonmyung Hwang You talked about how you found the balance between Korean, Korean American, and American identities. Before you found that balance, were there any struggles you went through?

“In elementary school, my dad really wanted me to do basketball. I was really interested in basketball - like watching it - but not really interested in playing myself, because all the white kids and black kids play, but there are no Asians. So, how do I fit in? I resisted doing anything like sports and all that, but my dad really wanted me to interact with those people. Even though there were no internal or external conflicts, he said that I should challenge myself overall and just because you’re Asian doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t try to do something you like.”

You said you were the oldest sibling. What would you want your sister to know about your family’s immigrant story?

“That it wasn’t easy. It wasn’t easy to come here. My parents always make it seem like it was easy. They continue to love us and go to work. The language barrier, the cultural barrier, and they had to take care of our family as well. So there was probably a lot on their mind when they came here, but they never really showed that aspect to us. So, I think that’s how we adjusted to American culture and at the same time, they instilled in us a sense of pride for our Korean heritage, so I hope my sister can really appreciate that about my parents and other immigrants as well.”

- Andrew Soonmyung Hwang

-

Manjari Sriparna

Manjari Sriparna What are some hardships that you and your family encountered or sacrificed to get to where you are?

“I think I remember being in the third or fourth grade and coming home to see my parents stressed out. Usually kids are supposed to see their parents like superheroes, as if they know everything and can solve any problem in the world. But when you overhear conversations about a parent struggling to find a job as soon as possible in order to stay in the country, it forces you to see the world in a different way and grow up a little faster than normal. Watching your parents grow up with you and deal with many hardships while you're still a kid definitely molds you as a person.”

What prompted you to share your story today? What do you hope to do? What do you hope to gain? What do you hope to give?

“I wanted to share aspects of being an immigrant because I think it's often exaggerated when people do talk about it, if at all. Like, ‘Oh, these immigrants are leaving their crappy hometowns to come to America.’ That’s not a fair narrative since immigrants often leave places they actually cherished, leaving behind all of their family and friends. I feel like that's where there's a superiority complex of saying, ‘America is so much better than other places and that’s why people come here.’ This misinformed perspective changes the way people treat immigrants, perhaps as though they’re second-tier citizens. I don't think that's a constructive perspective to have and changing that viewpoint is so important to ensuring all Americans are treated equally. I always joke that no one loves America as much as an immigrant loves America because they literally left everything that comprised their lives to come here. A lot of people don't understand that perspective and are quick to judge.”

- Manjari Sriparna

-

Yuri Chia & Ingrid Wu

Yuri Chia & Ingrid Wu You talk about having two homes. Can you speak a little bit more to that?

“Home is like - you have a sense of pride and happiness in where you are. When I’m in Taiwan, I like to say I’m proud to be American and when I’m here, I like to say I’m proud to be Taiwanese and Chinese. I like to share my pride with other people and try to encourage them to be proud of themselves and their heritage.”

- Yuri Chia (left)

Have you faced any misconceptions because of your immigrant status or identity?

“I think the general population thinks that Asians are all smart, all good at science and math, that we’re just born with it like magic. People don’t realize how hard we have to work. I guess I happen to be good at math and science, because both my parents are engineers, so that was expected of me. When I asked my father about an algebra problem in 7th grade, I had to stand for three hours explaining the whole theory behind how that proof evolved. My father said, ‘You work twice as hard, and maybe you'll get half the recognition.’ That’s the type of philosophy I had growing up… to say that Asians are super smart in science - I think that’s a disservice to some Asians, because there are those who have to work pretty hard at it. And that’s the key - we do have to work hard, and we do work hard.”

- Ingrid Wu (right)

-

Ingrid Wu

Ingrid Wu Have you ever felt like you were living with a certain stigma attached to you as an immigrant? If so, what is that stigma?

“I’ll start with the background. I know my father came to the U.S. before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, so he faced blatant discrimination. He actually came for graduate school, then civil engineering work in North Carolina on highways. He went to a hotel where it said there was a vacancy. When he went to ask for a room, they told him there were no vacancies even though the sign said otherwise. The guy behind him was white, and they gave him a room, so that was very blatant. This was in the early 60s - things have come a long way. When I went to Ruxton, I was the first non-Caucasian in the whole school. They didn’t even know where the Republic of China was. They knew about Japan because of World War II; some of the families had service people in Okinawa. I think we've come a long way. When I was here [at Hopkins] in the 80’s, there was no Chinese program, no Nanjing program. In fact, I was the interpreter when the delegation came from Nanjing to explore cooperation. I was only a freshman. Because I was fluent in Mandarin, I interpreted for Nanjing University's Vice President and delegates. We as students went to the deans and administrators. We said Hopkins is a major university, but there is no Asian language, culture course - nothing. We fought to get the first Chinese language class at the time. We built on it - next year we had two, then we had three. Now, you have the East Asian Studies Program. That’s how the Hopkins-Nanjing Center began. We really had to be diligent.

Traditionally, a lot of Asians are seen as very well behaved; we don’t complain about anything. Even now, I see the issues, and they’re seen as black and white. It’s very sad, because the issues aren’t just black and white. What about the Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans? I always bring that up. My background here at Hopkins: I was a math pre-med, but I also did Sociology, then international relations abroad and law school, so I’m very conscious. We as Asians have to realize that, yes, we are well-behaved, but we're often overlooked because we are so well-behaved.”

- Ingrid Wu

-

Yuri Chia

Yuri Chia Was there a particular stereotype that you faced?

“One stereotype was that people said that I’m communist because I identify myself as Chinese American and China is a communist country and one of the most dominant forces in the world today. Historically, America has always feared communism, so I’ve always been a number one enemy to the Americans, going back to the Cold War and the Soviet Union. So there is definitely a fear of China here and they try to put that on me, saying that I’m communist. But I’m from America and I’m not communist at all. And Taiwan is not a communist country. The Taiwan Republic is a democratic de facto state, so I was very angry. It’s not easy to understand political concepts like communism and democracy - they’re not concepts people can grasp very easily. So, on one hand, I can feel bad for them that they don’t understand and on the other hand I was very upset.”

- Yuri Chia

-

Jenny Jiang

Jenny Jiang Did you or your siblings encounter any hardships? Did you face any stigmas regarding your ethnicity?

“There has been so much stigma with being the only Asian - being different from everyone else in a group. But, that is not really my biggest issue. I don’t find it hard to deal with outside perspectives; I don’t really care about what other people think. But, I think the biggest problem I face is finding out who I am, exactly. I was raised in an Asian community when I was little, but coming to Virginia, there isn’t really a lot to know who I am, so I don’t really know what I became. So the hardest problem is finding out who I am.”

What are your best memories of your family’s immigration story?

“I wasn’t there when my parents immigrated, but I think the best part of having family connected to a different country is the memories that you build going to that country. You know that your parents grew up there, but it’s like an exotic land to you. It’s so weird seeing the mango trees growing outside the houses and the different environments. I think it’s really nice because you have your roots not exactly here, not exactly there, but essentially all over the place.”

Why did your family immigrate to the United States?

“My mom has told me that it was because the U.S. was considered ‘the land of opportunity’ and she thought that she could find something from it. For me, personally, I don’t really understand why, because she was considered one of the brightest students of her time by her high school teachers. But she dropped out of high school to come to America. I guess that’s how much she values opportunity.”

- Jenny Jiang

-

Kush Mansuria

Kush Mansuria Growing up, what is the biggest stigma that you faced coming from Indian culture?

“I think a lot of it comes from the immigration debate and I think that most people think, ‘We don’t want chain migration.’ I think chain migration is misunderstood by a large number of people. They don’t really understand how it works. They don’t understand that the three big countries - China, India, and Mexico - have the longest wait times for legal immigration into the US. So that pushes the idea that, ‘Oh, foreigners are coming to take our jobs,’ but if they’re coming here legally and for permanent residency, they won’t be able to come for about 20 years. My uncle, who filed for a work visa, filed for permanent residency around 2004 or 2005, but the government is still looking at applications from 2002 right now. So he doesn’t expect to be here for another ten years. So I think the idea that immigrants are stealing jobs is not true.”

What motivated you to participate in this project? What do you hope to gain or give from this experience?

“People don’t really talk about their past a lot, especially as second-generation immigrants. Maybe as second-generations, we talk a lot about our past to our friends, but definitely what I know about my culture comes from what happened since I was born, not really the history before. For the longest time, I didn’t know that my dad worked as a food delivery driver. He worked at a grocery store a few miles from my house. He eventually got a different job, but I was completely unaware that he was doing that when he came here. These conversations don’t really happen a lot between our parents and us. I think that sometimes it makes us lose perspective about what they went through. And part of it is also because they might not want to talk about it, but it’s definitely important to talk about it - to gain perspective about everything that they have been through, the struggles and all.”

- Kush Mansuria

-

Cyndy Vasquez

Cyndy Vasquez What would you say is the most challenging aspect of being from an immigrant family?

“I think it’s hard because not a lot of people personally identify with that background. And because of that, sometimes people can say some pretty ignorant things. For example, my best friend is a DACA recipient - she’s a DREAMer, from back home. So a lot of people would say, ‘They had it so long, so why don’t they become citizens?’ In the first place, it’s not like they’re even able to adjust their status. And both my parents are temporary protected status recipients and the Trump administration recently rescinded that program. So, right now my parents have until September 2019 to adjust their status or else they have to leave. And it’s hard - when I was at home for winter break, my dad sat me down and was like, ‘We’re going to try our hardest, but if we have to go back to El Salvador, you have to stay here and you have to graduate.’ So yeah, you have to come to terms with it a lot of times. And I guess that motivated me to do my best. Because I’m in a position of privilege where I can help people like them, like my friends and my family. I’m trying to make the best out of it.”

What motivated you to participate in this project?

“The political climate is very tense around immigration, especially considering Mexican/Central American immigration. So being able to put a face to a story, it might change their opinions around these situations and affect what they say. Because their words do affect actual people.”

- Cyndy Vasquez

-

Irene Bantigue

Irene Bantigue How would you describe your transition from the Philippines to England, and from England to the US?

“The transition from the Philippines to England - I don’t remember much of it. I just remember growing up and feeling that I don't fit in where I was, because I thought that was my home. And just feeling that something made me feel different. My family is super Filipino and them being so different from my other friends’ parents made me feel conflicted. Then moving from England to the US, I was definitely a lot more conscious about the diversity of the new place and finding my place in a new environment.”

What was the hardest thing about immigrating to the U.S. for you and your family?

“I think it was having to find that balance between fitting in and keeping a hold of your culture. Yeah, we still celebrate a lot of our culture at home, but it's very hard sometimes. We waited seven years for our immigration visas to be approved, and then in 2014, we moved. So it's just been a long time of failures and then starting over again. But I think it's impressive and it motivates me - hearing that my parents in general did not let the failures deter them.”

Why did you choose to share your story today? What do you hope to gain and what do you hope to give?

“I chose to share my story because I feel like I'm still a very Filipino person, culturally, even though I've lived in very Westernized places. I guess this is kind of a type of self-growth for me. I want to share how I've tried to direct myself through the process because it's difficult to try and settle in a completely different place. So that's why I was hoping to share my story. Even though I appreciate that my life has gotten so much better, moving from these different places, it came with a lot of sacrifices from my family."

- Irene Bantigue

-

Indu Radhakrishnan

Indu Radhakrishnan How much emphasis do you think you would place on imparting Indian culture to your children?

“That's something I've been thinking a lot about lately. Not about having kids, not yet - but how do I conserve something that I feel like I don't really have that much knowledge about? I would love to be able to pass on things like the language. But then there's the problem that I don't speak it that well even though I can understand it fluently. So I would love to impart a great deal of that culture. Especially the food and the language and the music. That's super. I feel like those things are the kinds of things that shape a lot of who you are and the things that you love and are interested in. But I also don't know if I have that capacity, which is really terrifying.

I went back to India recently. It was like the first time in 14 years I went back, and after going back it was like, ‘Wow, I do love this culture and this is a part of who I am.’ I want to be able to pass that on. I want to be able to bring my kids back there at some point. So yeah, it’s definitely a matter of making the effort, I think. I have a very close relationship with my parents, but of late I've been making more of an effort to build more of a cultural competency with them, you know. You know, if my mom is cooking in the kitchen, just looking over her shoulder and seeing what she's doing. I'm trying some of those things myself, even just going online, listening to more music of the Malayalam variety or watching more movies. Just trying to give myself a little context because I would really hate for me to be where the stopping point is for the culture. I want to continue it.”

Are there any common misconceptions people have about you because of your status as an immigrant?

“I think the big thing is that people make assumptions about my relationship with my culture. People either think I'm like this representative of my culture or they're just really surprised when they find out how American I am, but to me it's like I've spent all of a year and two weeks in India and I spent pretty much my entire adult life in America. So of course I'm going to be American. In a lot of ways I identify with aspects of cultures that are not my own. And I identify more strongly with being an immigrant than I do necessarily with being Indian, because I don't feel like I have that cultural competency with Indian culture to be like, ‘I'm an Indian person.’ I think the assumption with a lot of immigrants is that you are like a representative of whatever country your parents came from. And you're usually not, especially if you've lived most of your life in the States, unless your parents are really into the hyper-culturalization - most parents want their kids to be able to adjust well to society. You end up being pigeonholed as the Indian person.”

- Indu Radhakrishnan

-

Jae Choi

Jae Choi How has your immigrant background played a role in your life and shaped your identity?

“I moved to the U.S. when I was 9. That was actually the second time that I moved here. The first time, I briefly lived in northern California, but I was really young and don’t remember much about living there. In between moves to America, I lived in several different countries and was used to frequent environmental changes. Looking back on the second time I moved here, I remember my feelings throughout the immigration process pretty clearly. Moving to America the second time turned out to be a big culture shock. It was probably my most difficult transition. I remember feeling much more aware of my cultural identity and the ways in which I might differ from my peers. This isn’t true of all places around North Texas, but the suburban area that I lived in wasn’t terribly diverse. Some neighboring cities had more populations of different backgrounds, but I was probably the only Asian kid at my elementary school when I moved to Texas. It felt weird. There was an obvious language barrier, which caused miscommunication with my peers, but there was also a heightened awareness of how different I was from others. I remember experiencing some bullying as a kid because of my cultural and ethnic background. And I think that kind of aggression and all those negative interactions just made me more and more self-conscious as I got older. For a long time, I didn’t enjoy life in America very much. I’ve gotten used to living here since then. Those memories don’t bother me as much now and I’ve been identifying myself as an American citizen since gaining citizenship when I turned eighteen. I like living in America now, but it was still a difficult time in my life.”

What prompted you to share your story today?

“I definitely wanted to share my story because I want people to understand that immigration isn’t easy. It can be stressful, difficult, and pretty alienating. And I hope that, through the stories that are shared, immigrants at Hopkins can feel like their experiences as immigrants weren’t experienced in isolation - especially for people who come from rarer countries. I know there are a lot of students from places like Korea, China, and France, but I know there are some other students who feel isolated just because of how far removed their country of origin is. I’m hoping that I can help contribute to a better sense of mutual understanding among people.”

- Jae Choi

-

Gyuri Han

Gyuri Han How has your or your family’s immigration story played a role in your life or shaped your identity?

“I moved to the US when I was nine years old, and I moved to the US without knowing a single word of English, so that was a really huge transition for me, especially in terms of making friends. So I would say I was pretty insecure up until seventh grade. That’s when I actually felt comfortable speaking in English. And I think that’s when I officially considered myself fluent in English. And, throughout that time, I think I was really afraid to speak to people. I was very insecure and actually pretty shy when I talked to people. But now I am very outgoing and I’m very social, and I would really love to talk to even strangers. And I think that’s also because I used to be too afraid to speak to people because of the language barrier - now I want to reach out to other people if they are shy to make them feel more comfortable.”

Is there anything you would want to say to your younger self when you had just immigrated? Or to any other immigrants who are facing similar hardships?

“The biggest thing I would probably say is to trust in yourself. If you feel that there is no one else to depend on externally, depend on yourself, because in the end, it’s you who will be comfortable fitting into the society that you are in. And in the end, you are going to be completely fine as long as you believe in yourself and trust that whatever you do is what you’ll be proud of, and whatever you do is what you represent as an immigrant and how you contribute to the society.”

What prompted you to share your story today, and what do you hope to give to your community?

“Well, I definitely feel like I’m not a unique immigrant. All immigrant stories are very unique and have individualities, but I feel like I’m just one out of thousands and thousands of people. And, I feel that the more stories that are told, the stronger the impact will be. I just want the rest of the campus and the rest of the society to realize that people do come really far from where they were, and that people can actually turn over the table and just show themselves and express themselves as who they are in a way that’s not affiliated with or, I guess, converted in an American society. We have our own little culture, and we are very unique, so I feel like sharing my story is good for spreading that.”�

- Gyuri Han

-

Milena Berhane

Milena Berhane How has your or your family’s immigration story played into role to your adaptation here?

“One thing my parents told me and my siblings that they thought was important when they first came to the U.S. is that being open-minded is key. You have to be open-minded because you would want people to be open-minded to you. It is wrong to criticize others for superficial things, and it is better to judge someone's character by getting to know them. The U.S. is a mix of many different cultures and personalities, including your own culture, so you should be open and accepting to others. When my parents first started working and getting adjusted, they didn’t face much discrimination because the D.C. area is so diverse, but there were often times where people in the workplace or other places would pick on them for their accent or their lack of knowledge on certain American customs. But, my parents also told me that being open-minded does not mean you should make excuses for people. You should not allow yourself to be disrespected, and stand for yourself when you are being disrespected. So, that's one rule I have used throughout my life.”

How do you alleviate, or reconcile the two sides of your identity?

“It can be kind of hard sometimes, trying to find a balance between the two sides. My sister and I always joked about us living a double life, having Eritrean cultural activities to tend to on the weekends and hanging out with our school/American friends during the week. I really appreciate my parents teaching us about our Eritrean heritage and speaking to us in our native language because it has been an important aspect in making me who I am today. But, sometimes I feel like I struggle to balance the two sides. I want to hold my Eritrean values close, but not completely override the American values that have been reiterated all of my life. In order to find that balance, I have kept both my Eritrean and American perspectives at the forefront and not let one take over the other. It's harder with my parents, sometimes explaining to them certain topics that are not within their traditional mindset, but they are learning. They taught me to be open-minded and accepting, and it is amazing to see them also become open-minded to many things as well.”

- Milena Berhane

-

Isabel Rios-Pulgar

Isabel Rios-Pulgar Were there any challenges that you faced when you came to America?

“I remember when I was in New Jersey, when I was younger, my parents and I were speaking in Spanish. We received the stereotypical, ‘This is America. Speak English,’ comment and my dad turned around and said, ‘Shut the hell up.’ Other than that, I have been blessed with less discrimination than other people, because I was able to live in a very Hispanic community.”

How do you think your family’s background has impacted your identity?

“Well, the first thing that came to mind was the spirit of perseverance. My parents tried to instill that in my little and older brother and me - you should work hard for everything that you get. And when I came to Hopkins, it’s also the spirit of family and community. This idea is super prevalent in every culture, but in Hispanic culture, putting family first is important. Not only with blood-related family. Everyone in Doral is considered my family, so coming to Hopkins was a good example of that.”

What are your thoughts on the current President?

“I don’t know where to begin. This is my personal, genuine opinion. The whole DREAMer situation was a lot, especially since a lot of people from my community are DREAMers. To have the President push that aside and forget about it, like…can you please, sir? Lives are on the line, sir. I relate to people that say they don’t have anything at ‘home,’ because the United States is their home. I relate to that, even though I immigrated here legally. I think the political climate is doing exactly what it shouldn’t be doing, and that’s letting people’s differences push them apart instead of pulling people together. It still gives me a glimmer of hope when I see people go out to protests.”

- Isabel Rios-Pulgar

-

Richard De Los Santos Abreu

Richard De Los Santos Abreu Have you ever felt there is a stigma attached to being an immigrant, or even more specifically from the Dominican Republic?

“Absolutely, I think there are stigmas attached to three big things: being an immigrant, being Hispanic and coming from the DR. Being an immigrant, people see it from two different perspectives. One, you came here to get better opportunities because you didn't have any in your home country, because of your financial status or because of some governmental issues in the country that you didn't agree with. Or two, you can be seen as the cream of the crop, seeking not for better opportunities - because you already had a good financial status in your home country - but for better quality of life. It's often understood that Hispanics tend to get lower-paying jobs and they tend to be from low-income families. You get attached to that stigma. If you came to the US and you are Hispanic, you must be from a low-income family, with no education and no desire to speak English. Dominicans who come to the US are usually sent to jobs related to gardening or housekeeping, especially in Manhattan. That’s where most of the Dominicans are located - or in Washington Heights. The stigma is there for a reason; stereotypes exist for a reason. But we must not generalize, and I think society is changing. The new wave of immigrants is changing. We are better prepared, and we have a lot more desire and motivation than other Americans. We came to the US to strive, so it’s what we're gonna do - it’s what we're doing.”

- Richard De Los Santos Abreu

-

Giuliana Nicolucci-Altman

Giuliana Nicolucci-Altman How has your family's immigration story played a role in your life or shaped your identity?

“I think it's done so in so many ways. First and foremost, because of the languages I was brought up with, I speak Portuguese with my mom and Spanish with my dad… which first of all, gave me the ability to not only communicate with my family, but with other people who speak Spanish. Also, I think growing up as an immigrant, you grow up with this mentality of having to work twice as hard because of the opportunities that your parents presented to you via their sacrifices and the the hardships that they had to experience to get you to where you're at. So I think that's really shaped my motivations and and it's gotten me where I am today.”

How did you parents instill these ideals in you?

“Comparing both my parents, my dad doesn't really consider himself to be an immigrant. He’s moved around a lot and he studied abroad, so he feels more like he's never completely settled. My mom, on the other hand, established a whole community of friends in the U.S. of other Brazilians, and she perceives it to be a blessing to be in this country and to leave Brazil. I'm not sure if you know much about Brazil - that daily reality, the disparity between the rich and the poor in Brazil. And so I think that mentality was more passively instilled because my parents never put too much pressure on me to do well academically. I'm just using academics as an example because to them, that's how you get places. I think it was more of me observing and reflecting on what they had to do and then taking it upon myself, because the thing that would make me the happiest would be for them to be proud of me. So with whatever I try to do, that's my motivation.”

- Giuliana Nicolucci-Altman

-

Brandon Park

Brandon Park Please tell me a little bit about yourself.

“I’m a freshman from Northern Virginia and I’ve lived in Virginia my entire life. My parents struggled a lot as immigrants, especially since I was the only Asian in my entire grade and I would’ve been the only Asian in my entire school if it weren’t for my brother. In that area, there weren’t a lot of Asians my age. There were a lot of elderly Asian people. So my parents didn’t really find a lot of friends to talk to. They struggled a lot. My dad was the one going out and interacting with people in English and my mom didn’t develop those skills as quickly.

There was one time our toilet broke and a plumber had to come over. In Asian households, you don’t wear shoes and my mom knew that the plumber probably would not get that, so she tried to sound out to him and piece together a sentence and she said: ‘Can you step on the newspaper?’ or ‘Do you mind wearing these shoes because I can just vacuum later?’ But the plumber took this as an insult and ended up yelling at my mom, and he ended up leaving without fixing the toilet. So my mom started crying and called my dad. I didn’t know what was happening since I couldn’t speak English.

We finally brought our first house in 2013, so it’s been 15 years of renting and living in apartments. It was a huge accomplishment for them. I knew my parents worked hard. After we moved to Northern Virginia, my mom took on a job, because my brother and I could take care of ourselves at that point. I realized how much they worked. They’re in their 40s now, but I looked at them once and I started crying because I remember after they told me that story, I started working and studying more. I joined clubs and I did everything I could so that I could become successful one day and pay them back, so that they would never have to work again.”

- Brandon Park

-

Bonnie Jin

Bonnie Jin What are some challenges you have faced in coming to terms with your immigrant identity?

“I think that for a lot of immigrant children, they have to grapple with the fact that at home they are one person and at school they are someone else - they have to present several different faces. But for me, it’s a lot more like at school I am a person, but when I’m at home, I don’t know who I am. A lot of my identity revolves around the fact that parts of my family sided a lot more with China and parts would side with Taiwan. There’s a lot that I don’t know about my own family that I’m still trying to figure it out.”

Even though you immigrated here when you were so young, have you ever felt like you were living with a certain stigma attached to you?

“I think that what’s unique about me is that I don’t necessarily focus only on politics in East Asia. I’m really interested in European politics. I’m an Asian American who is somehow interested in Europe. That’s somehow an anomaly, because most people who are Asian American and do International Studies tend to focus on East Asia, which makes sense because of their personal identity. For me, in high school, I actually spent a year in Germany and that really changed my perspective on not only what it means to be an Asian American in the U.S. but to represent that identity abroad. For example, when I was in Europe, when people see that I’m Asian, they don’t think ‘Oh yeah, you’re American.’ I think it’s a lot about educating people and understanding that they just don’t know. Or the fact that even today, when you think about a stereotypical American person, the first thing you think about is not an Asian American. So, I think it’s important that more Asian Americans get involved in a lot of different careers and put ourselves out there and be like, ‘This is who we are.’”

- Bonnie Jin

-

Susan You

Susan You "The first vivid memory I have of someone who looked like me was Wendy from the Disney Channel movie, Wendy Wu: Homecoming Warrior. I was shocked to see an Asian cast for an Asian-American plot. Although I am not a Chinese immigrant, I felt a connection between me and Wendy because of her difficulties blending two different cultures in a very American community and setting. The mix of languages - weaving in and out of her native tongue and English - was something I related to. The heavy emphasis of cultural survival and pride was something that hit home."

- Susan You

-

Allison Jiang

Allison Jiang "I first saw myself in Violet from The Incredibles. I must have been very young, but even then I was aware that, as an Asian person, there were certain spaces I could not occupy and certain roles I could not play. Violet Parr and I had the same straight black hair, and she was shy and soft-spoken, just like me; but when the time came, she was fierce and brave. She loved her family and would do anything to protect them. These were the same qualities I loved about myself, but I had never seen them represented in someone who I truly identified with. I wanted desperately to be Violet, and even though I knew she was not Asian, I convinced myself that she might be. Even though Violet made me feel like I could be brave and amazing and beautiful, I wish I didn't have to pretend she was not white. "

- Allison Jiang

-

Shaina Morris

Shaina Morris "The first time I saw myself was not in a successful actor sharing my racial identity, a courageous heroine in a novel, or even a prize-winning female scientist. The first time I saw myself was in a drunken, raunchy, animated horse with a long-dead acting career and a penchant for self-destructive activities.

Bojack Horseman, the title character of the Netflix comedy, resonated with me in a way that no kind of media had before. His development throughout the series centers around his persistent depression and substance abuse, with hard hitting realism far from the glamour of Thirteen Reasons Why and The Perks of Being a Wallflower. My personal struggles with these exact issues were mirrored in the show, my frustration encapsulated in the quote 'I don't know why I feel shitty! I just want... to not feel shitty anymore.' Finally somebody, even a fictional horse, understood my persistent emptiness, nihilism, and apathy. Finally here was somebody who understood my substance use as an escape from a meaningless life.

Bojack Horseman showed me that it's okay to let myself feel the way I do, but also that 'it gets easier.' 'But you have to do it every day, that’s the hard part. But it does get easier.'"

- Shaina Morris

-

Victoria Lai

Victoria Lai "There were a couple East Asians dotted all throughout media when I was growing up (Trini the Yellow Power Ranger, Mulan, etc.), but everyone felt very trope-y, or they were clearly just a side piece with no conflict of their own. Then in 5th grade, I stumbled across a book at the school book fair with a young Asian girl on the cover, dressed in a baggy purple sweatshirt, hair pretty plain and pulled back into a simple ponytail - cheesy at it might sound, she looked the exact same way I did that day. The book was entitled, "Child of the Owl," and it changed the way I felt about myself as an Asian American. The protagonist, Casey, is ethnically Chinese, but is raised completely outside her Chinese heritage. This changes when her father is sent to the hospital for long term care, and she is forced to move to San Francisco's Chinatown and experiences extreme culture shock, and is constantly rejected by the society as a whole for behaving like a good Chinese girl. The author describes her as being "too American to fit into Chinatown, and too Chinese to fit in anywhere else," and it resonated with me in a way not even my family (Chinese immigrants) could understand. Being the first on both sides of my family to be born in the US, it constantly felt like I was deep in the middle of a huge gulf between American culture and Chinese culture, and no one was willing to help me out of it. It was the first time I'd seen another Asian girl as not some exotic doll to be trussed up in stereotypes and marched about as the token minority, but a human with conflicting feelings about expectation, family dynamics, and culture. The book doesn't have a "happy" ending; she's still caught between two worlds, but she ultimately finds a sense of serenity in knowing the beauty of her lineage, which is more than any of us find, sometimes"

- Victoria Lai

-

Tiffany Bui

Tiffany Bui "I was a big Lil Peep fan, so I started exploring music in his genre and discovered Cold Hart, the co-founder of Gothboiclique. It was rare to see other Asians in the emo movement as it's usually considered a white boy thing. Cold Hart coldly embraces his fashion style and self-expression, and comments openly about mental health, all the while being memey. It made me feel reassured that just living my best self when I'm out there being edgy was OK, and that I didn't need to conform to what people expected of me. And of course, his music is great."

- Tiffany Bui

-

Aran Chang

Aran Chang "Seeing myself for the first time in media is a process that's still happening now, as I learn more about my identity. First time seeing an Asian American in popular media was through American Dragon: Jake Long from Disney. First time seeing a trans Asian American in popular media was last month actually through an Instagram star."

- Aran Chang

-

Zoya Sattar

Zoya Sattar "The first time I 'saw myself' was in the book Blue Jasmine by Kashmira Sheth. Although I say I grew up in Oklahoma, I spent much of my childhood moving between America and Pakistan. I had a very confused perception of what it meant to be American, South Asian, and the daughter of immigrants – I had thought of these things more as being separate identities than existing together.

Blue Jasmine was the first book I recall reading with a Desi-American character, one that hit on all the points of feeling torn between two spaces where years of distinct experiences laid. I'm pretty sure no one else got the chance to read it in elementary school because I would check it out so often!"

- Zoya Sattar

-

Smitha Mahesh

Smitha Mahesh "It was when Priyanka Chopra starred in the TV show "Quantico." When the first scene of her aired on ABC channel, I was amazed that this bold, brave, liberated, and brilliant character was instilled in a woman that looks like me. Priyanka Chopra has worked very hard to make it into the American media light, from movies to songs and now television. Every episode captured my attention because the show made it very clear - Priyanka Chopra, a woman like me, is real, is authentic, and is very much a symbol of liberated womanhood. And that is so important to me. Growing up as an Indian-American 1st generation child, my parents instilled in me the beautiful values of Indian culture and Hinduism. However, while growing up in American culture, having Indian blood within me made it frustrating and a lonely experience to not see someone like me in any form of media, much less a liberated bold Indian woman in the media. It was because of Priyanka Chopra, Lily Singh, Deepika Padukone, and so many more inspiring women in media that I had strength and courage to be my freely-expressed self."

- Smitha Mahesh

-

Josena Joseph

Josena Joseph "The first time I saw myself in popular media was when I discovered Superwoman on YouTube. Her experience as an Indian woman who struggled with assimilation and rationalizing Indian culture in Western society really resonated with me Growing up, my family was very distrustful of popular Western ideals, and that created an internal battle for much of my childhood. Seeing that other people had gone through similar experiences was really empowering."

- Josena Joseph

-

Isabel Rios-Pulgar

Isabel Rios-Pulgar "The first time I saw myself was with Gina Rodriguez’s character in Jane the Virgin. She was not only raised in a Venezuelan household like me but was also a very driven and independent character with a lot of pride in her identity, which are qualities that I try to apply to my own daily life."

- Isabel Rios-Pulgar

-

Kush Mansuria

Kush Mansuria "I think the first time I saw myself in a mainstream way was in Slumdog Millionaire (2008). I actually haven't seen the movie, but I remember hearing the buzz about it at home and in school. My parents were especially excited as this was the first time they saw significant South Asian casting in a mainstream film (that was not Bollywood). I think for them, being in America for almost 15 years at that point, they were excited to see Indian Americans being cast as leads and not accessory roles like a taxi driver or convenience store owner.

More personally, I related with the Bollywood film, 3 Idiots (2009), especially the main character. I found the main character's take on life and how he dealt with its challenges inspiring, which is why I continue to watch it. It has also become my go-to film to show to my friends and others, and it has had many positive reactions and conversations, which I find encouraging."

- Kush Mansuria

-

Frishan Paulo

Frishan Paulo "The first time I saw myself was when I was a young kid watching TFC, The Filipino Channel. But she wasn’t quite me; she was a half-Filipina celebrity with pale smooth skin and Caucasian features who would still be considered more Filipino than me because she was actually from the Philippines. While I, a small brown Filipino-American girl with too big eyes and a too wide nose to be considered anything other than Filipino was still not Filipino enough since I’d been born and raised in America. I had asked my mom if that lady on TV was the same ethnicity like us. Later, she had me washing exclusively with papaya soap and told me to stop rubbing my nose as if it would get wider. That was the first time I saw someone of my ethnicity.

The first time I saw myself was when I was 8 years old. It was Katara from Avatar the Last Airbender. She is a brown girl, a powerful waterbending prodigy who used her skills to actively fight and dismantle the patriarchy of both the Northern & Southern Water Tribes, as well as save the whole goddamn world. Aang would have been lost without her. But really, it wasn’t so much that I saw myself in her so much as I had wanted to be her. I wanted to be strong and independent and cause change in the world. I dressed up for her that Halloween because someone said I was too brown to be Toph. That was the first time I saw the person I wanted to be.

The first time I really saw myself was last year, when I was 21 years old. My friend suggested watching a cheesy movie for his birthday, so Filipino Students Association watched The Debut, a movie from 2000 featuring Dante Basco. I saw myself in Basco’s character, a young boy who was so initially ashamed of his Filipino heritage that he wanted to skip his sister’s debut (which is pretty important for Filipinos) and tried so very hard to separate his white friends from his home life. I watched him argue with his parents, and I watched him struggle to speak his native language, much to his family’s embarrassment and disappointment. I watched him come to the realization that maybe he loved being Filipino. I cried when I watched this movie. I had never seen anything capture my exact struggles with my culture and heritage and experiences. “Honestly same” was the phrase of the night. This movie came out when I was 4 years old, but it’s so old and obscure; there’s a good possibility I never would have heard of it had it not been for my friend. Where are the Filipinos in the media? East Asians got their turn with Crazy Rich Asians. I think it’s Southeast Asians’ turn now."

- Frishan Paulo

-

Brenda Quesada

Brenda Quesada "After I arrived in America (Miami, Florida), I remember being up late at night as my parents discussed our immigration status. I turned on the television and "I Love Lucy" was playing. The first time I saw myself in television was in the form of Lucy's husband, Ricky Ricardo (played by Desi Arnaz), who was a Cuban singer and the leader of his band. Seeing a Cuban character, played by a Cuban actor, on television in America surprised me very much. I was used to watching Spanish cartoons back in Cuba, and I hadn't really seen "myself" in anything. Coming to America, I expected to only see white people and their struggles. I never really knew the impact of Desi Arnaz on television until much later in my life.

Ricky Ricardo had a lively personality, cared deeply about his wife, and loved his Cuban heritage. Hearing him talk so fondly about Cuba, his love for both his parents (as well as arroz con pollo) and slipping into Spanish during heated moments, made me proud to be Cuban. Seeing his struggles as an immigrant trying to “make it” in America and live the American dream gave me hope as an immigrant that one day, I could be like Ricky Ricardo. I could contribute just as much as he did to making this new country my home by embracing my Cuban roots and using them to make my experiences in America richer. I could live out my own version of the 'American dream'."

- Brenda Quesada

-

Bex Lo