Minstrelsy

The minstrel show was a form of theater that surfaced in the 19th century, featuring skits of white performers in blackface makeup. These skits, built upon caricatures of African Americans, were interspersed with instrumental songs, ballads, and dances. Widely recognized as the first unique form of entertainment in the United States, minstrel shows quickly became the dominant form of American performance for decades. Minstrel instruction books were even published with audience-tested tips for using burnt cork to become a "darkey":

"Be careful to get the black even around the eyes and mouth. Leave the lips just as they are, they will appear red to the audience. Comedians leave a wide white space all around the lips. It makes the mouth appear larger and will look red as the lips do. If you wish to represent an old darkey, use white drop chalk, outlining the eyebrows, chin, whiskers, or a gray beard."

While white supremacy may not have been a stated objective of minstrel shows, it was undoubtedly a result. African Americans were depicted as lazy, buffoonish, unintelligent, and violent. Characters such as the happy-go-lucky slave emerged, singing wistfully about their time on the plantation. In "Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America," Robert Toll notes:

"It was no accident that the incredible popularity of mintrelsy coincided with public concern about slavery and the proper position of Negroes in America. Precisely because people could always just laugh off the performance, because viewers did not have to take the show seriously, minstrelsy served as a 'safe' vehicle through which its primarily Northern, urban audiences could work out their feelings about even the most sensitive and volatile issues." (Toll 65)

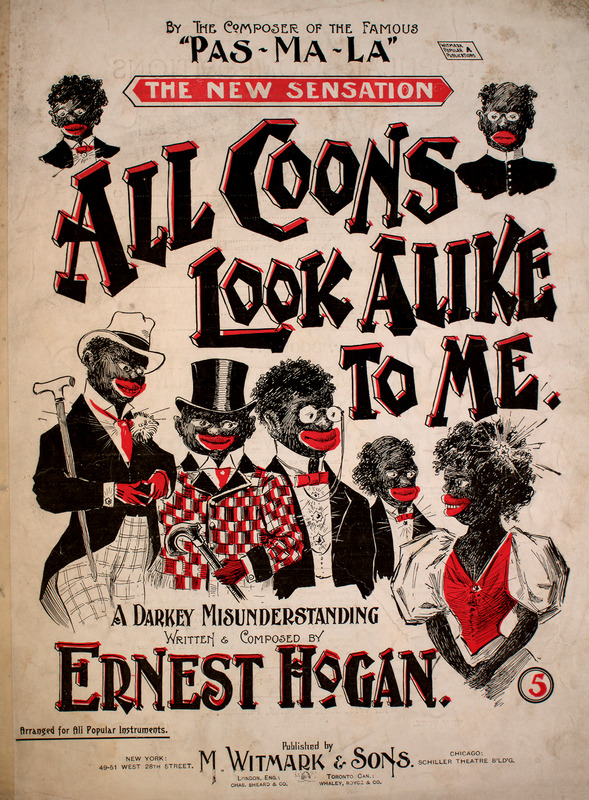

Even powerhouse New York publishing companies like M. Witmark & Sons participated in the minstrel craze. In an autobiography about the company, Isadore Witmark describes the entertainment: "Rooted in the plantation pastimes of the Negro slaves, it caught both the ecstasies in which subject peoples are so ironically rich: the gleeful abandon and the sober, religious preoccupation with an after-life that shall compensate for the sorrows of the present" (Witmark 131). He continues, "Yet this does not mean that our darkey songs, as written by the whites, are altogether insincere. The Negro has become for us a mask from behind which we speak with less self-consciousness of our own primitive beliefs and emotions."

Depictions of Slavery

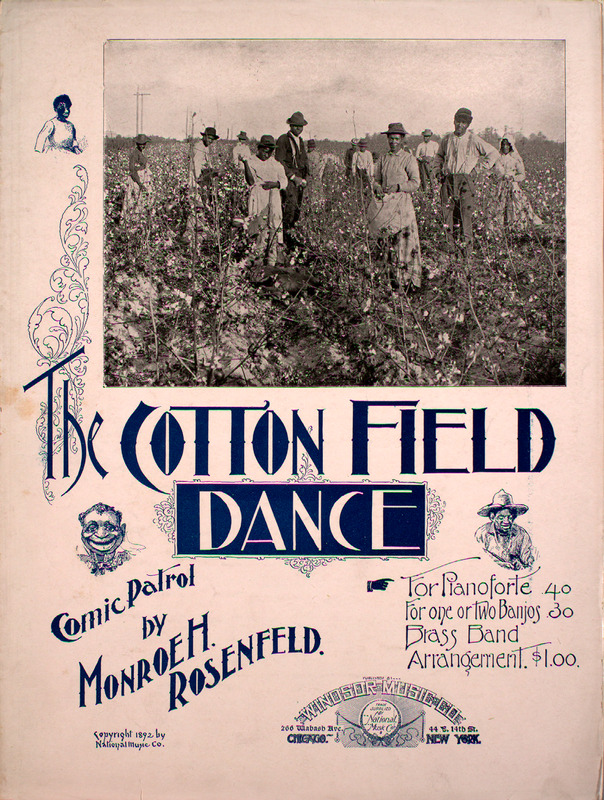

Numerous minstrel songs depicted enslaved persons as joyful or mischievous. The Cotton Field Dance (1892) appears to have a photo of enslaved persons on the cover, as well as caricatured cartoons of them below the title. This oxymoronic song was distributed in at least Chicago and New York, and arranged for a variety of ensembles (piano, banjos, and brass band). The composer, Monroe H. Rosenfeld, was well-known at the time, composing more than 1,000 songs and coining the term "Tin Pan Alley." The style of the music is upbeat, with popular ragtime rhythms similar to the music of Scott Joplin, implying the cotton field was a place of joyful dance.

In discussing white performers in blackface makeup, Toll notes, "Again and again, minstrel blacks recounted how their kind masters took care of them, gave them all they wanted to eat, indulgently let them play and frolic, and proudly helped them set up their own households within the broader plantation home like a model extended family."

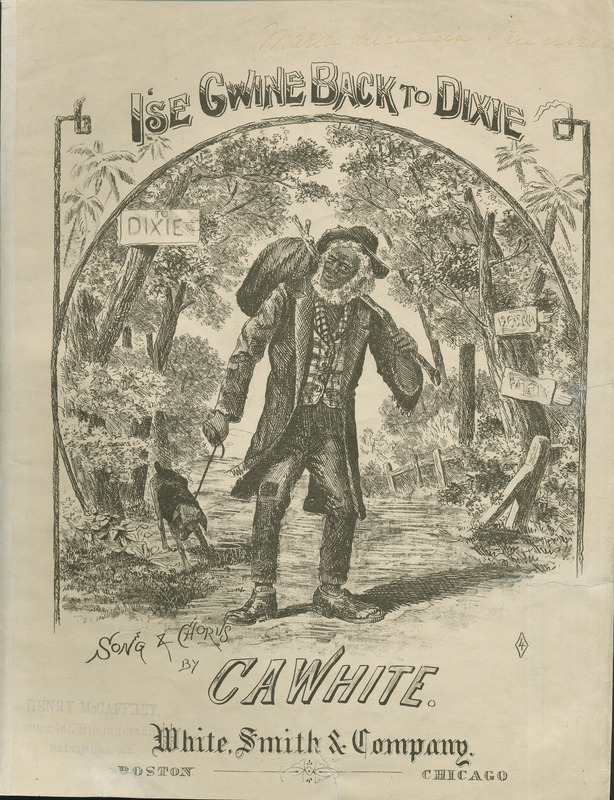

"I'se Gwine Back to Dixie" features the African American dialect used heavily in minstrel songs. In this undated song (circa 1880) published in Philadelphia, an unhappy former slave misses "de ole plantation" and wishes to return home. The music (recording here) features a contrast between upbeat dance and sentimental ballad-- it even includes a chorus of four voices, implying the narrator is not alone in their wish to return to Dixie.

Black Performers

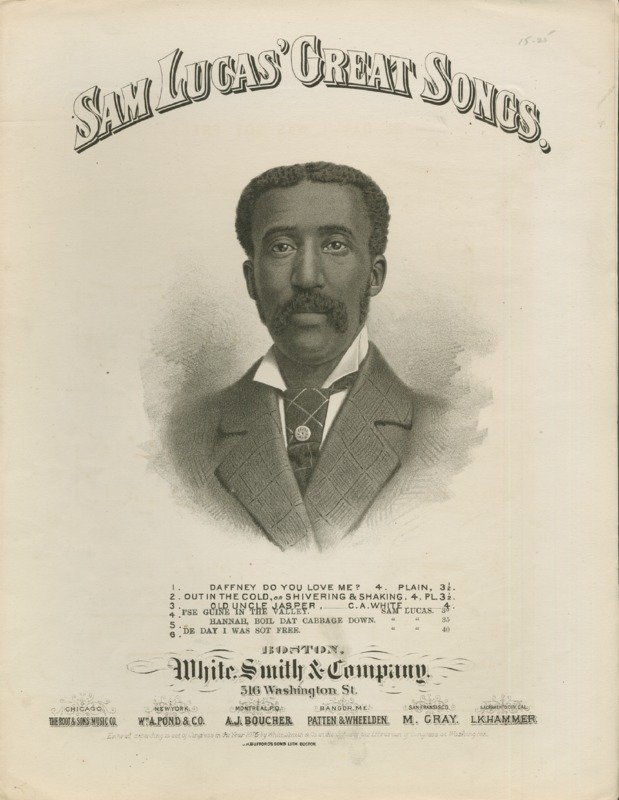

Many minstrel shows included contributions from African Americans, either as performers or composers. This song was written by Sam Lucas, a composer born to free black parents in 1848. Lucas' career began in minstrel shows, but his career turned serious when he became the first African American to play the title role in "Uncle Tom's Cabin" in 1878 (the year this song was written). Mellonee Burnim & Portia Maultsby, in "African American Music," offer an explanation for why a black performer might join a minstrel troupe:

"What seems to us a monolithic and repulsive racist format...may have appeared to free Blacks who aspired to the stage more like an opportunity to subvert or amend the message of minstrelsy by substituting a new messenger." They also quote black minstrel performer Tom Fletcher: "The objectives were, first, to make money to help educate our younger ones, and second, to try to break down the ill feeling that existed toward the colored people." (Burnim & Maultsby 189)

A serious rendition of the song can be found here.

Coon Songs and the Legacy of Minstrelsy

Songs that presented stereotypical images of African Americans were often called "coon songs." Here, the word "coon" is short for "raccoon" and was widely used as a racial slur (Burnim & Maultsby 127)

This song, promoted as "the new sensation," was published in 1896 by M. Witmark & Sons (quoted above). Besides the numerous racist depictions of Black people on the cover, the lyrics are from the perspective of a Black man who's been turned away by a woman (also Black according to the cover) because she thinks all "coons" look alike.

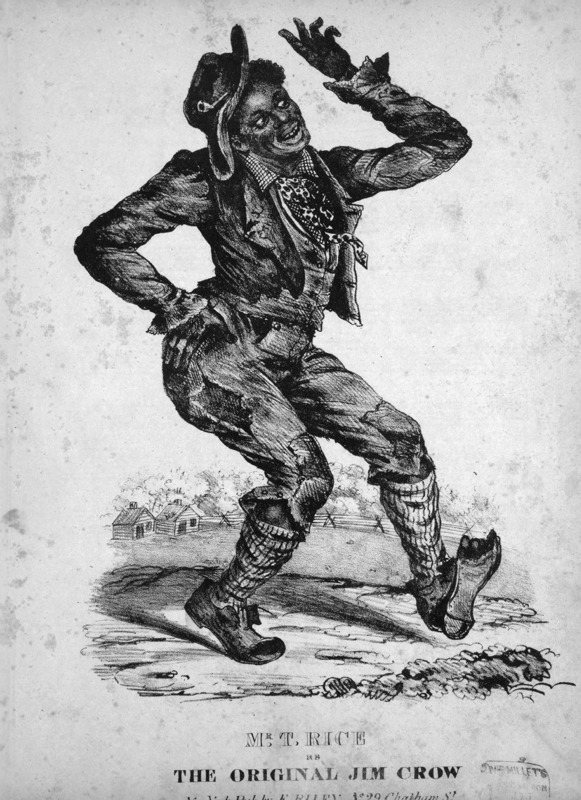

Jim Crow was originally a minstrel character, dressed in rags and lacking manners or wit. The character was made famous by Thomas Darmouth ("Daddy") Rice, often called 'the father of American minstrelsy.' Jim Crow would eventually come to symbolize the laws that enforced racial segregation in the United States.

The slur "coon" has also persisted in white supremacist culture. Travis McMichael, one of three men who murdered black jogger Ahmaud Arbery in February 2020, had previously used the slur in text messages with his friend Zachary Langford, referring to a "crackhead coon with gold teeth." When the text messages were read aloud in a courtroom, Langford claimed, "(McMichael) was referring to a raccoon, I believe."

Birth of a Nation

Minstrelsy also found its way into film, even featured by period celebrities like Al Jolson, Judy Garland, and Fred Astaire. In 1915, the silent film Birth of a Nation was released, becoming one of the most controversial movies in cinema history. The film portrays African Americans as violent and sexually aggressive, while the Ku Klux Klan are depicted as heroes, introduced as "the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule."

In addition to the use of blackface characters, the musical accompaniment to the film is used to associate different characters with evil or triumph. Towards the beginning of the film, a melancholy cello melody accompanies images of slaves. Later in the film, the slave quarters are shown, and the music instantly changes to ragtime rhythms that would have been associated with Black Americans-- here, we see the slaves happily dancing in their off-work hours. When a black militia is introduced (around the 40 minute mark), the music becomes chaotic and violent. The Ku Klux Klan, in contrast, is introduced with trumpet fanfare.

The text cards of the film also reflect some of the themes found in popular song lyrics. When the Cameron family is introduced (around 6:30), a seed is planted for the loss of their culture: "Piedmont, South Carolina, the home of the Camerons, where life runs in a quaintly way that is to be no more." A white character, in the face of interracial marriage, is depicted in "agony of soul over the degradation and ruin of his people."