Representation and Romance

Romance comic books of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s were often formulaic—a general premise would be that a beautiful young girl got herself into some kind of trouble, leaving her lonely and in despair, but then it would all be fixed by some boy-next-door type affirming his love for her. And that beautiful young girl was often cut straight from a cookie-cutter: white, able-bodied, straight, thin, and from a suburban, middle- or upper-class family. But not all romance comic characters came from that mold—sometimes they touched on people with underrepresented, marginalized identities, such as people of color, fat people, disabled people, LGBTQ+ people, and the lower-class. But how did the comics handle the portrayal of those identities? How did those representations reflect the time period in which they were created? The following comics book covers explore these questions.

Sophia Lola, Curator

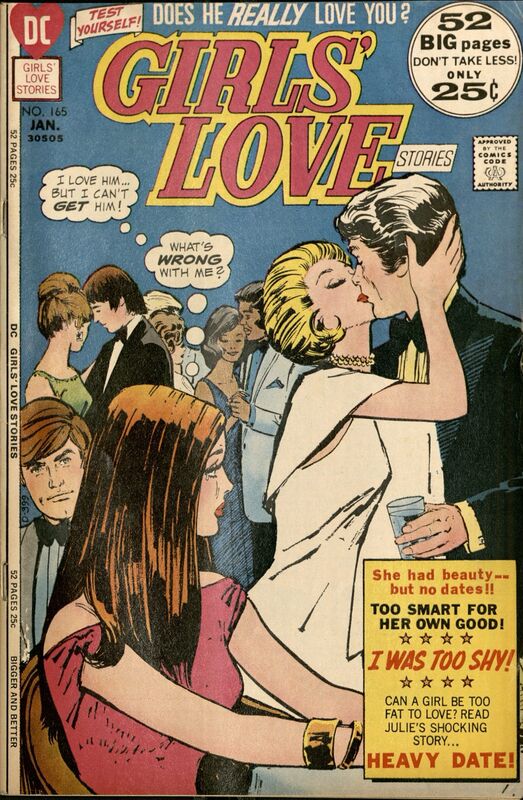

Girls' Love Stories. No. 165, DC Comics, 1972.

“Heavy Date” is about an overweight teen, Julie, who is excluded from her friend’s party because of her size. But then she meets a boy, Earl, at a diner. Earl likes her, but also wants her to change; he sees who she could be if she were to lose weight, and he can fill the unhappy void in her life that must have made her overeat and become fat. Julie starves herself to lose weight. Once she’s thin, she tries to steal the boyfriend of her friend, Ellen, who bullied her, to make a point about how bad it feels to be left out and humiliated. Earl thinks she has become catty and mean, so he leaves her, and she starts to eat more and gain weight back because she misses him. Once Julie is fat again, she apologizes to Ellen, and she runs into Earl at the diner. He tells her not to eat the ice cream she ordered and takes her back, saying it’s time for her to “start living again!” Presumably she will lose weight for him again.

The story ultimately conveys that fat women are unhappy, lack self-control, and don’t deserve love the way they are; men only want thin women, and a man’s love will be a fix-all for their health and body image issues. It is also worth noting that this issue contained a second story as well, and the cover of the issue illustrates that other story, perhaps because the publishers thought that showing the overweight protagonist of this story on the cover would have been off-putting or unattractive for potential readers.

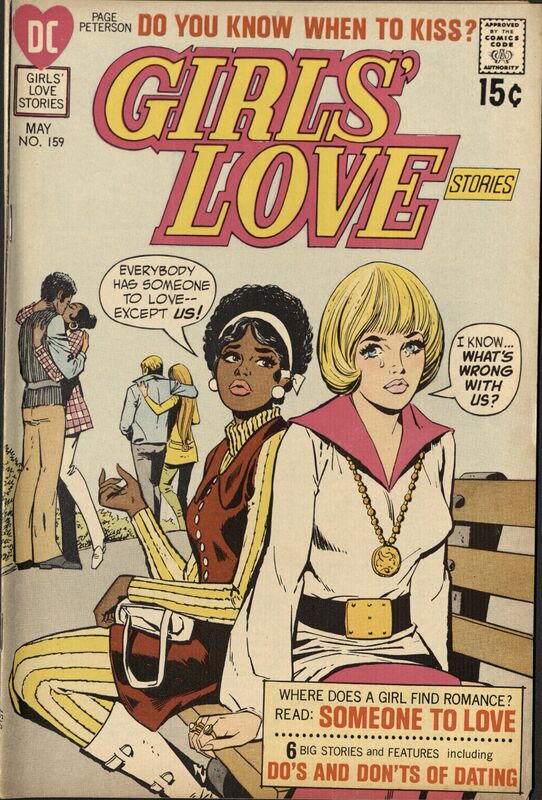

Girls' Love Stories. No. 159, DC Comics, 1971.

“Someone to Love” focuses on two best friends, Celia, a white teenage girl, and Angela, a Black teenage girl, as they both enter their first relationships with boys. The beginning of the story tells how Celia and Angela originally became friends when they were young: Angela’s family moved next door to Celia’s family, which sparked a racist protest by other residents to keep the neighborhood segregated. Celia’s family, with some encouragement from Celia herself, went to introduce themselves to Angela’s family and welcome them to the neighborhood, which led the two girls to become friends. In this way, the comic is promoting and normalizing interracial unity and friendship, which, in the wake of the civil rights movement and the backlash against it in the 1960s, seems very progressive.

However, Angela still seems to be somewhat sidelined in the story. Though both girls get the happy endings and boyfriends they want, the plot of Angela’s relationship is given less attention than Celia’s. And there is a moment when Angela tells Celia she’s going to step in to help Celia with her boyfriend issues, saying that “Auntie Angela” will fix it. The specific use of the word “auntie” calls to mind the mammy trope of Black women existing to help white people, rather than existing as their own person. The composition of the cover image, with Angela sitting slightly behind Celia rather than next to her, seems to reinforce that Angela is not a main character and that, like with many others, the “true” protagonist of this romance comic is a white woman.

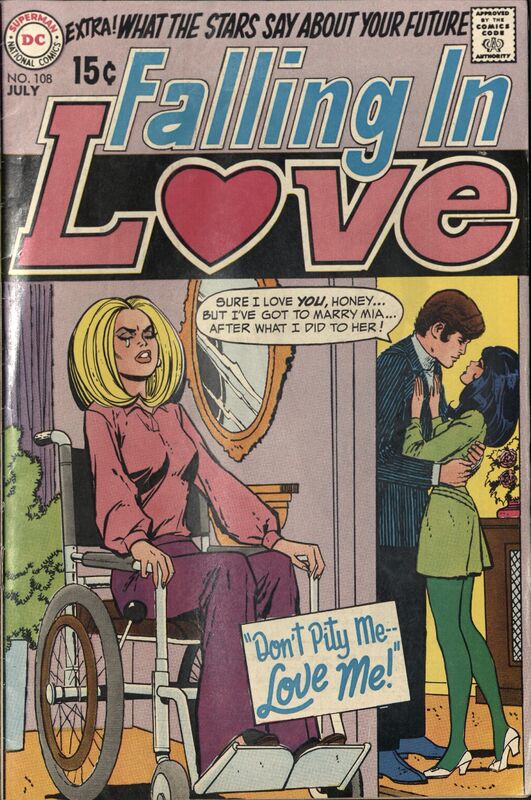

Falling in Love. No. 108, DC Comics, 1969.

"Don’t Pity Me, Love Me” is about a girl named Mia, who, after being injured in a car accident caused by her boyfriend, can no longer walk and must use a wheelchair. At first, her boyfriend, Richard, still dotes on her and promises to take care of her and be there for her for the rest of their lives, but Mia is worried about being a burden to him. When her friend Lois, who is able-bodied, returns from being away, the three of them begin to spend a lot of time together, until Richard and Lois start spending time just the two of them. When they think she is napping, Mia overhears Richard and Lois talk about wanting to be together but not being able to because Richard feels responsible for taking care of Mia after he caused the accident. Mia later tells him she heard and breaks up with him because she doesn’t want to be with a “male nurse” or someone who marries her out of guilt. The next day, Mia has a doctor’s appointment where she finds out she will be able to walk again. Richard returns to tell her that he doesn’t want to be with Lois, that he wants to be with her, again saying he wants to take care of her. Mia tells him that he won’t have to since she will recover, and they get back together.

The idea of a disabled person being a burden or obligation to others is very prevalent in this story. It has the ableist implication that disabled people cannot be self-sufficient, cannot have lives on their own, and cannot contribute positively to society and the lives of others. Having a partner as a caregiver is a part of some disabled people’s relationships, but Richard’s emphasis on wanting to stay with Mia so he can take care of her (rather than just because he loves and wants to be with her) seems to suggest that disabled people are unworthy of true, romantic love, which is also ableist. The happy ending reinforces this, since it is contingent on Mia no longer being disabled and on her not having to “burden” Richard. Lastly, her quick forgiveness of Richard implies that it is okay for disabled people’s loved ones to mistreat them without consequence. The cover image for this story, which shows Mia crying in her wheelchair as she overhears Richard telling Lois he loves her but feels responsible for Mia, illustrates these ableist ideas of disabled people being burdens and unworthy of love and happiness.

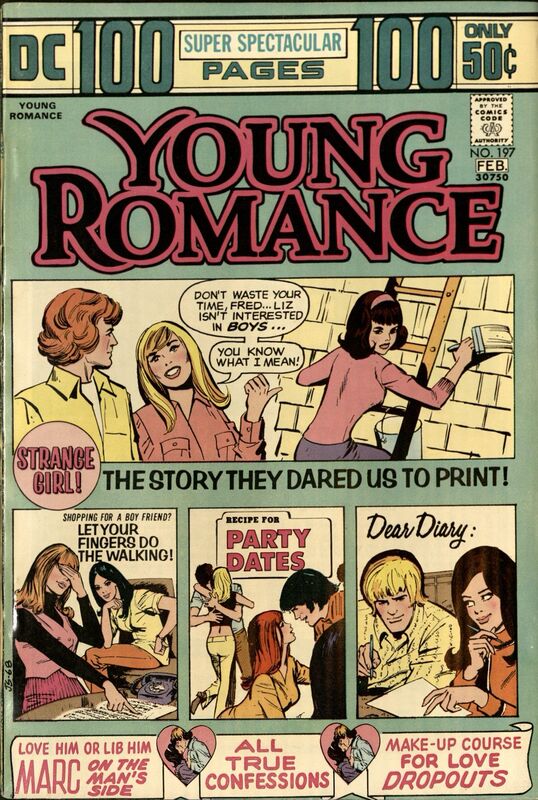

Young Romance. No. 197, DC Comics, 1974.

“The Strange Girl” focuses on Liz, a teenage girl who is a tomboy. She doesn’t have girly-girl friends, nor boys who are interested in her, and that doesn’t bother her! Well, not until she meets a boy, Fred, at her basketball game. He flirts with her, but Liz thinks he must be making fun of her like everyone else does. She finally believes he’s into her when he declares his love for her in front of her family. Throughout the story, people make snide comments about Liz’s “masculine” dress and behavior, implying that she must be a lesbian. The speech from the blonde girl on the cover, “Liz isn’t interested in boys, you know what I mean?” is an example of this.

While there are queer women who dress and act "masculinely", the association between queerness and tomboy-ness in this story is largely based on a stereotype, on the idea that a woman who likes other women cannot fit into any female gender norms because she wants to be like a man, she has something wrong with her womanhood. This story was released in 1974, not long after the Stonewall uprising and the free love movement, both of which made the queer community in the US more publicly visible. As a publication approved by the Comic Code Authority, the comic could not say the words “queer” or “lesbian,” nor feature a character who was actually gay, but the comic seems to imply that girls who may have those “tendencies” need only find a nice young man to remedy them, like Liz did.

Young Love. Vol 3, No. 5, Prize, 1960.

"Hunt Eloping Teenagers" is different from many other romance comics in that its main character is a teenage boy, Jerry, rather than a teenage girl. Jerry goes on a date with Hortense, who is the daughter of the town's rich factory owner, but Hortense doesn't pay much mindto Jerry until a few weeks later when she see him out with another girl, Trudy, who Jerry really likes. Hortense gets jealous and tells him that he needs to come back to her or else she will be forced to take steps. Jerry, whose father is the foreman at the factory, interprets this to mean that Hortense will get her father to fire his father, so he starts to date her again and they eventually sneak off to elope. Jerry's father, knowing that his son does love Hortense,finds them just before they say "I do" and halts the proceedings. Jerry's dad and Hortense reassure him that his dad definitely won't lose his job if he decides not to be with Hortense, with Hortense claiming that's never what she meant and apologizing for acting out of jealousy. Jerry gets back together with Trudy, and the story ends happily.

The story touches on a grim reality of class dynamics: wealthy power-holders can and often will exploit and mistreat those who they have power over, such as their employees. Hortense's initial warning that she will take steps is scary to someone who knows his socioeconomic status is lower than hers, someone whose family's livelihood depends on her father and possibly her. When Hortense says that of course she never meant her words in that way, which makes it seem like Jerry was overreacting, his justifiable fear and concern for his family is invalidated. Whether it is out of idealism or willful ignorance, the story denies the extent to which the wealthy wield power over the lower and middle classes. This class dynamic is subtly illustrated on the cover image, through clothes. He is wearing what looks like a rugged and worn work coat, the only hint of his economic status that drives his actions.