The Strange Girl

Romance comic heroines, especially ones written after the formation of the Comics Code Authority in 1954, often adhered to a very patriarchal view of women: delicate, feminine, and in search of a man to fall in love with. Heroines who broke away from this image, either by being relatively unfeminine or not desiring a relationship, were often described as “weird,” “strange,” or “crazy.” Oftentimes, likely in an effort to dissuade such traits, the plot would develop in such a way that these characters would become “normal” by the end, typically through their interactions with a male love interest. The rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s resulted in more characters who broke away from this patriarchal image, but even then, the fact remained that most romance comic writers were men, and thus the idea of finding a man being paramount stuck around. In today’s world, many of these “strange” heroines wouldn’t be so strange, and many of their struggles would be, in fact, relatable.

Jerry Chen, Curator

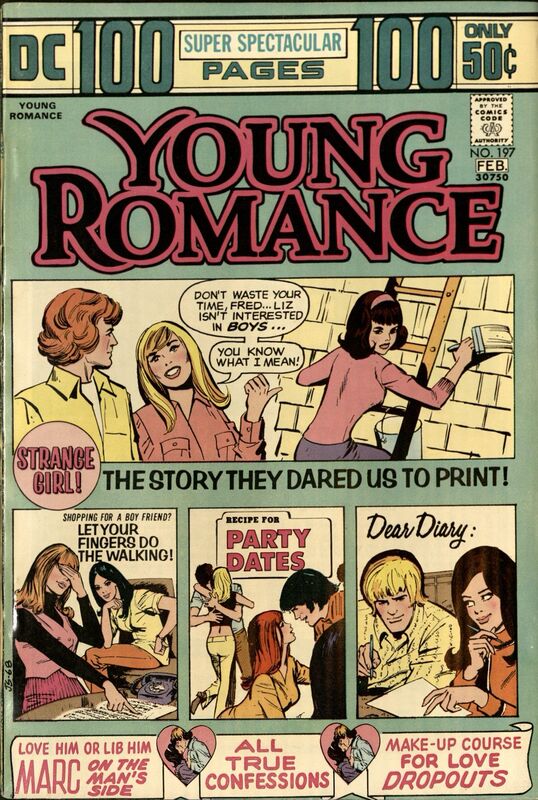

Young Romance. No. 197, DC Comics, 1974.

This story follows the perspective of a tomboyish teenage girl. As seen on the cover, this causes her to be the subject of teasing from her peers and concern from her parents, most of whom consider her to be strange. The comic page itself even labels the panel “Strange Girl!” The struggles the girl faces and her arguments with her parents are genuinely relatable, though the story ultimately comes to the conclusion that all she needed to solve her problems was the love of a boy, once again reflecting the pattern of any deviance from the patriarchal image of a young woman being cured by a man’s love.

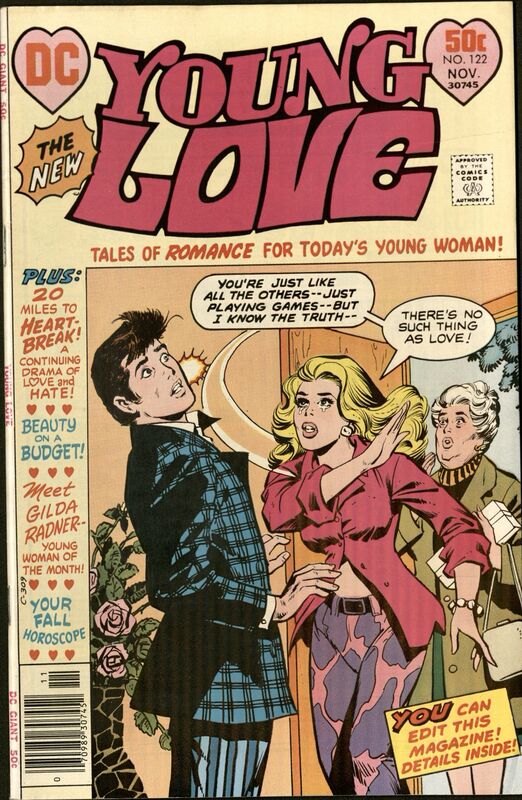

Young Love. No. 122, DC Comics, 1976.

In this story, we follow the perspective of a man who finds himself inextricably attracted to a mysterious woman. She is, however, disillusioned about love, and despite his (overly assertive) advances, she stands firm in her belief that “there’s no such thing as love.” This conflict gets reflected in the cover art through a physical smack. The man finds her lack of interest in a relationship “weird," and goes to the lengths of digging up her address and questioning her mother to ultimately try to find an explanation. Ultimately, her stance is attributed to past trauma, and she is suddenly involved in a car accident, thereby transforming her character from a “weird,” mysterious woman to a damsel in distress both physically and emotionally.

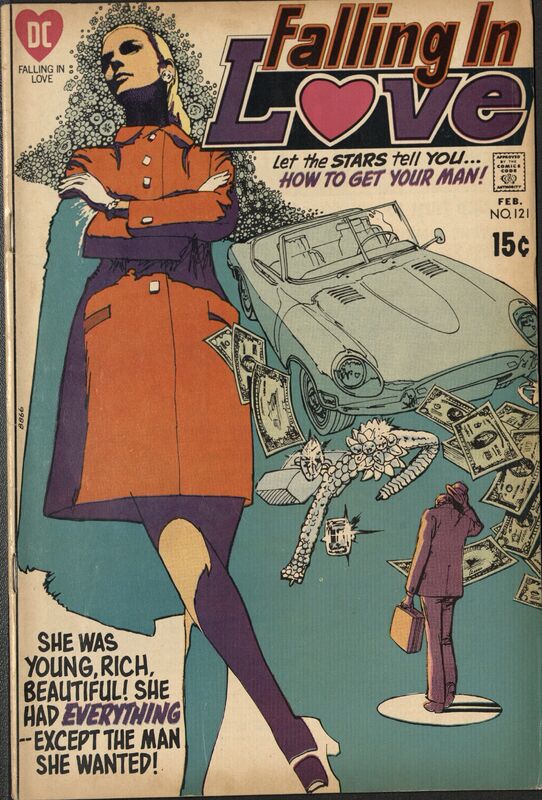

Falling in Love. No. 121, DC Comics, 1971.

This cover art fully reflects the heroine’s Women’s Lib-based beliefs as well as her outright professional success. The low angle shot portrays power, her arms are folded, and light shines on her from above, casting a shadow down to where we see a man, drawn to not even one fourth her size. In the story, she finds herself forced to choose between becoming editor-in-chief or maintaining her potential relationship. Ultimately, she chooses love over the personal goal she’d been working so hard for, and then as a plot twist, it’s revealed that she only got the job offer because the man turned it down first for her sake, undercutting the achievement somewhat and signing off with a reiteration of the idea that the relationship is paramount.

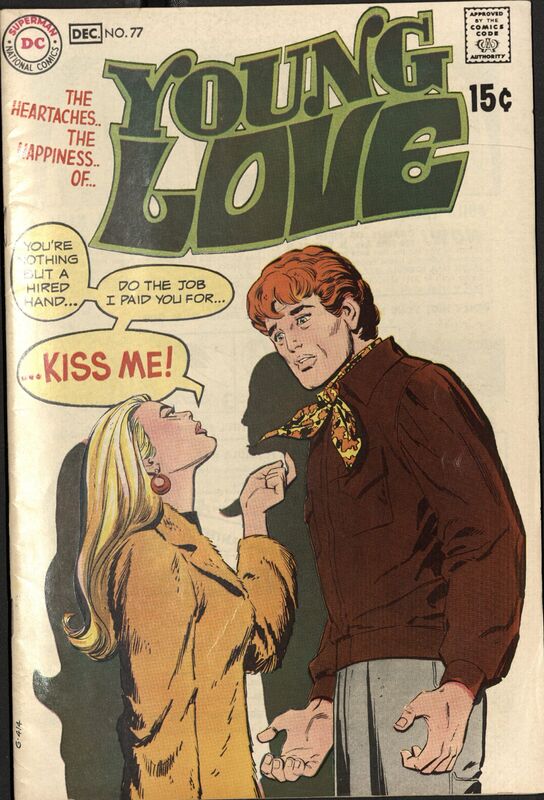

Young Love. No. 77, DC Comics, 1969.

This cover art reflects a relationship where the woman, the serialized character Lisa St. Clair, is in a position of power. She beckons the man with her finger and gives him a command, whereas the man looks relatively unsure with his eyebrows slightly raised and palms facing up. Relative to other romance comics, this is fairly rare. It could, perhaps, even have been considered weird at the time. However, this story doesn’t follow the same strangeness-gets-cured arc that the other examples have. In fact, it never explicitly calls the relationship weird, and for at least this chapter of the story, nothing in particular changes about their power dynamic. Notably, the woman is still otherwise very feminine, and becomes quickly interested in a relationship, so it seems that those two criteria being adequately filled, no strangeness-cure is needed.

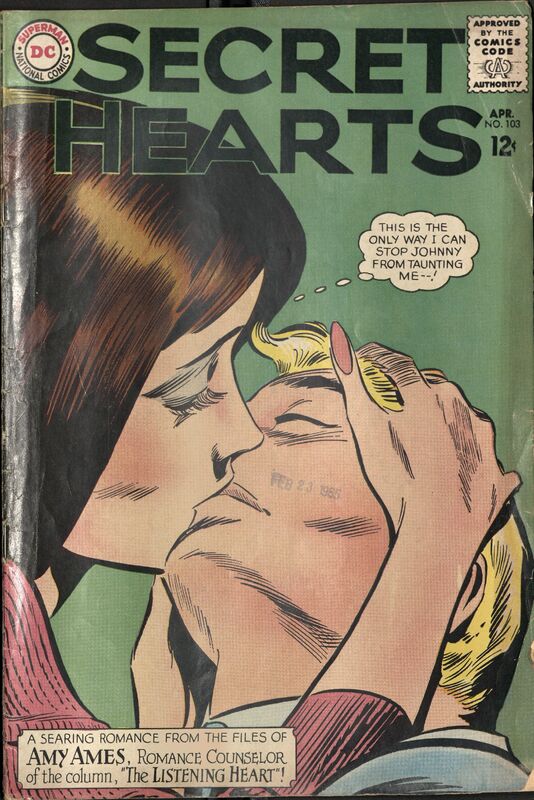

Secret Hearts. No. 103, DC Comics, 1966.

This cover art shows a scene that’s seen quite often in romance comics, except the woman and man have switched positions. The man has his head back as the woman holds and kisses him. This is not a display of power as in Young Love No. 77, but more so one of enthusiasm and desire. However, it is also not called weird, despite being so rarely depicted, as the woman is both feminine and in search of a man to call her own.