Teenage Counterculture

Starting in the 1960s, romance comic books delved into the world of teenage counterculture. In these stories, young women yearn to embrace a countercultural life away from the comfortable suburbs, involving motorcycles, hippies, protests, and music festivals. Such symbols served as shorthand for a rebellious and changing youth culture. However, the countercultural life is only successful if their is redemption. Using the trends popular among teenagers at the time, these romance comics sent a message to their pre-teen and teen girl readers that there is a limit to how much they can rebel and that instead, they should follow the rules and norms defined by society at the time. This set of post-1960 romance comic books highlight the intrigue young women had with a life less ordinary.

Ana Kuri, Curator

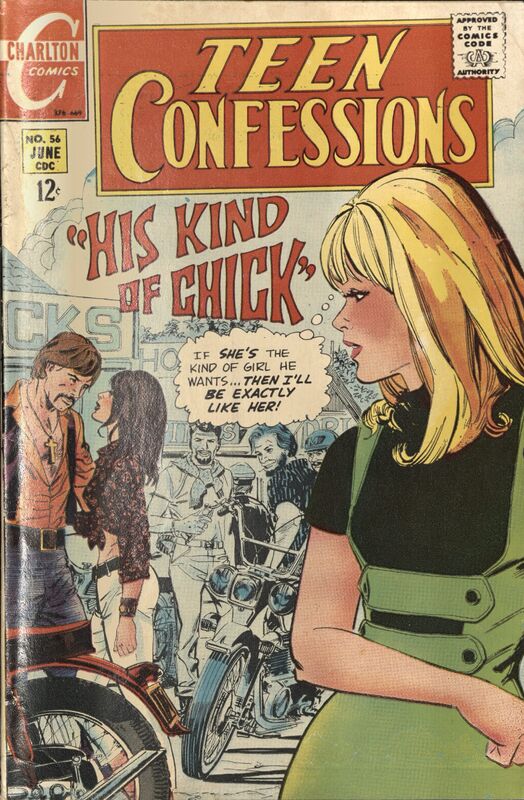

Teen Confessions. No. 56, Charlton Comics, 1969.

This cover depicts motorcycles, a symbol of counterculture representing danger, excitement, and free living. The dark-haired woman is dressed provocatively for the era with her stomach exposed and is wearing dark lipstick, which gives the impression that she’s rebellious. On the other hand, the blonde woman is dressed more modestly and is wearing a lighter, more natural lipstick color, making her seem more like a conformist. But with thoughts of becoming like the dark-haired woman to get the guy interested in her, it’s inferred that she will succumb to this counterculture life. However, the story itself reveals that the dangerous motorcycle man is actually an undercover agent, and the modest blonde woman is truly "his kind of chick."

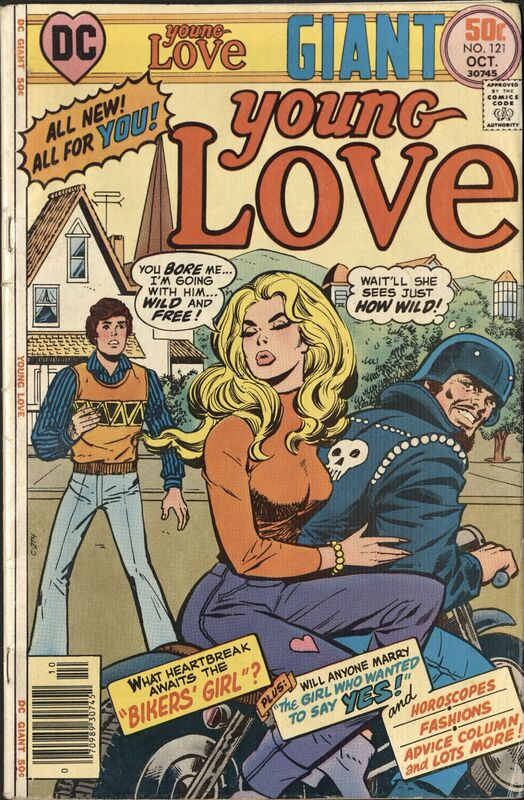

Young Love. No. 121, DC Comics, 1976.

The man on the left represents an upstanding man in society: he has a clean-shaven face, an innocent expression, and is neatly dressed. However,the young woman is bored with him and leaves him for a biker who looks like a miscreant with his motorcycle, skull embroidered jacket, facial hair, and cunning expression. She is rejecting the traditional lifestyle for a wild and free and dangerous lifestyle.

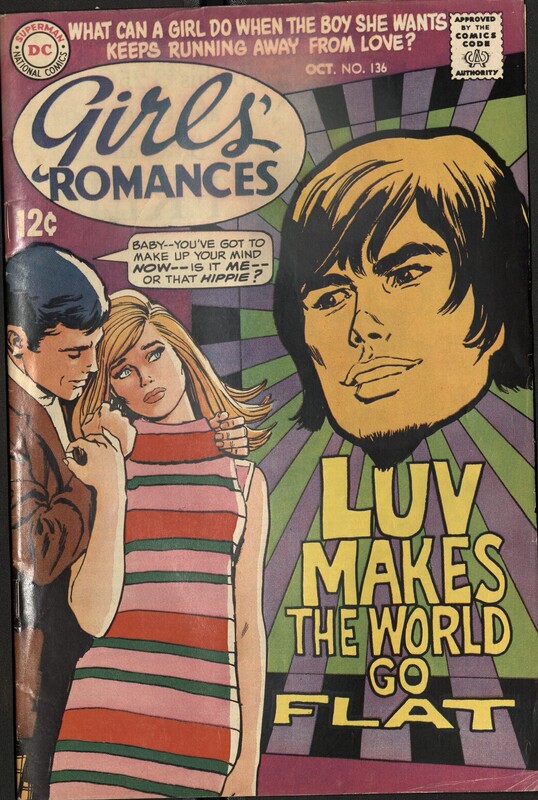

Girls' Romances. No. 136, DC Comics, 1968.

In this cover, the male love interest is a hippie: he has long hair, a beard, and is shown against a psychedelic background. In contrast, the girl's new suitor upholds the social norms of society. The girl is is conflicted about whether she should join her hippie love interest in his counterculture lifestyle or listen to her parents and her suit-wearing boyfriend to conform to a mainstream lifestyle.

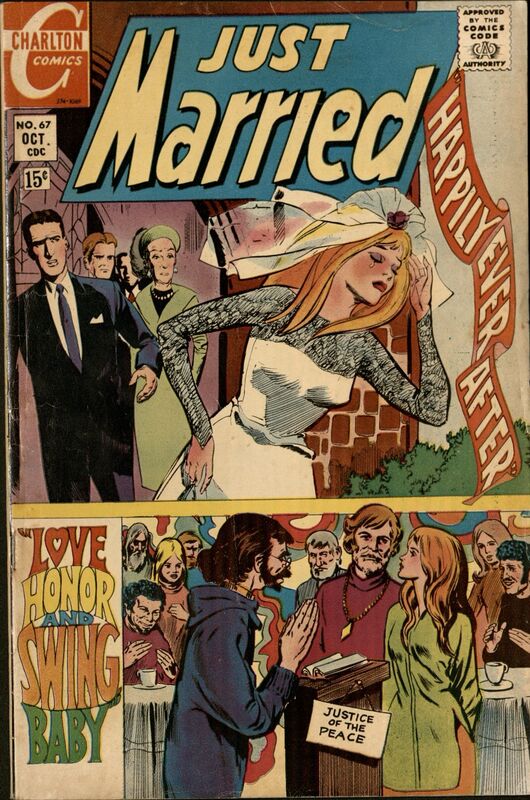

Just Married. No. 67, Charlton Comics, 1969.

The bottom image shows a woman getting married in a non-traditional way and illustrates the start of her counterculture life, which is revealed in the story to be an unhappy one. The man she is marrying is a hippie: he has longer hair, facial hair, and a long beaded necklace. The ceremony is in a coffee shop, they are wearing everyday clothes, and their wedding officiant is a "mod-mod comic" named Zuza none of which adhere to a traditional wedding.

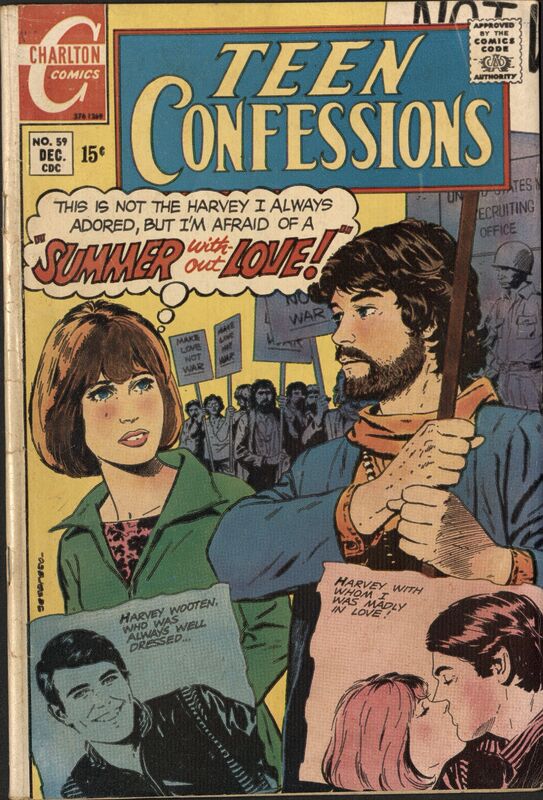

Teen Confessions. No. 59, Charlton Comics, 1969.

Not every young woman is enchanted by an alternative lifestyle. The cover story is called "My Summer Without Love, " playing upon the notoriety of the 1967 "summer of love." As seen in the bottom portraits, our heroine's boyfriend used to be more conventional: he was clean-shaven, smiling, and had kempt hair. However, consumed by the counterculture life of protesting against the Vietnam War, he becomes unruly: he grows facial hair, stops smiling, and has messier, longer hair. The heroine's thought that he is not the man she had adored, and her saddened expression reveals her dislike of his new countercultural life, which she will try to save him from so they can happily be together again.

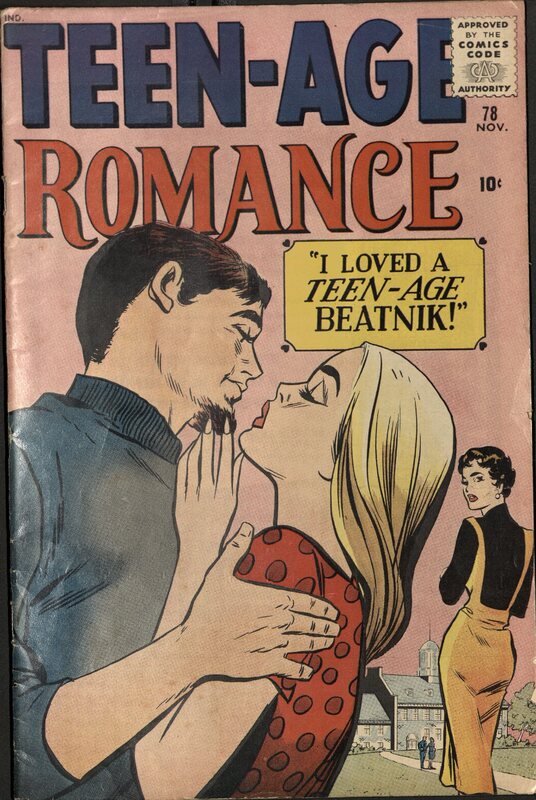

Teen-Age Romance. No. 78, Marvel Comics, 1960.

In this cover, our heroine is embraced by her boyfriend, a teen-age beatnik. The stereotype of the beatnik, a person who rejects mainstream behavior and values, evolved throughout the 1950s. The goatee and shabby clothes are part of stereotypical beatnik attire. In the background, a teenager stares back judgmentally at the two lovers, illustrating the aversion felt about their alternative lifestyle. Our heroine soon becomes irritated with her beatnik boyfriend and breaks up with him after he refuses to help save her father from dying in a fire.

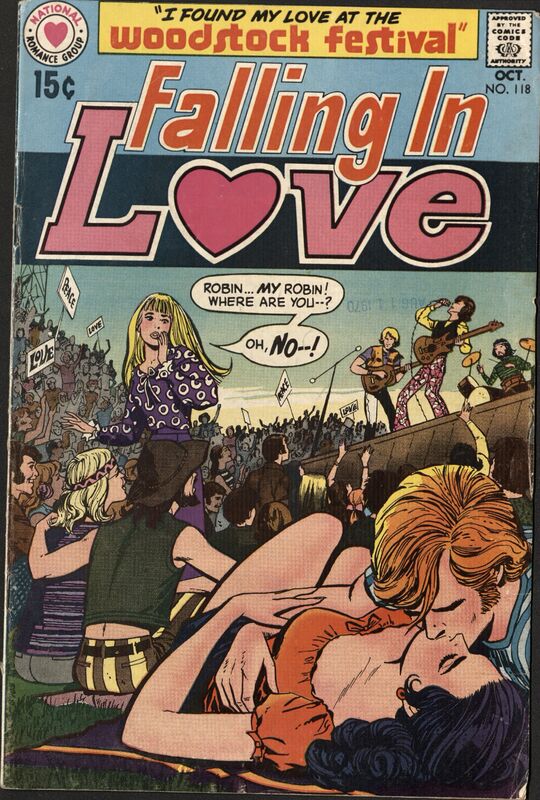

Falling in Love. No. 118, DC Comics, 1970.

In this cover, teenagers are at the Woodstock Music Festival, a major countercultural event. This festival was popular among hippies, as shown by the peace and love signs and the attendees' clothing. Woodstock exemplified a wild and free lifestyle. It was perceived negatively by mainstream, conservative society as being drug-filled and rebellious and thus was looked down on. From the blonde girl’s reaction to what seems to be her lover kissing another girl, we begin to see just how troublesome this counterculture lifestyle championing free love can be.