The Crying Woman

After the introduction of a comic book code in October of 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America, romance comic books quickly became limited to certain styles, scenes, and themes deemed ‘appropriate’ for audience-viewing. These plots affirmed long-standing traditional beliefs about gender roles and the societal dynamics of America at mid-century. Specifically with romance comic book covers, the cover art of a crying woman became popular as a way to capture the turbulent and emotional dilemmas of love while avoiding the use of overly sensational or provocative images associated with Pre-Code comic books. The depiction of women in such a vulnerable state was intended to sway readers to feel the same emotions – to feel the same pain and heartbreak that the female character endures. “The Crying Woman” soon spurred a new era within the romance comic genre, where authors attempted to reflect social movements and concerns through the feelings of a crying woman. In doing so, violation of the comic book code could be avoided, all the while sticking to the accepted styles and conventions that the comic book code bolstered.

Curated by Mitali Barik, Lily Chen, & Tran Ngomai

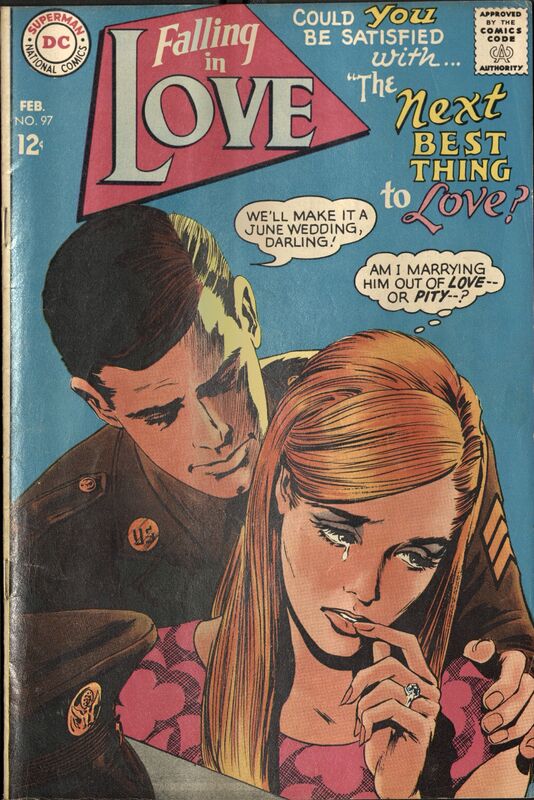

Falling in Love. No.97, DC Comics, 1968.

The cover exemplifies the typical portrayal of the crying woman as shorthand for inner conflict and indecision. Here, the heroine is torn between two major decisions: whether to marry her boyfriend or not, and if she does, is it out of love or pity? The cover art is quite tame without any outbursts of anger, frustration, or emotional instability. A single tear is enough to communicate the extent of her suffering to the reader. This issue was released during the Vietnam War and at ata time when the Women's Lib Movement was gaining raction. Perhaps crying is not a reflection of her submission to her boyfriend, but was rather a move to show that empowerment, independence, and emotion can all go hand-in-hand.

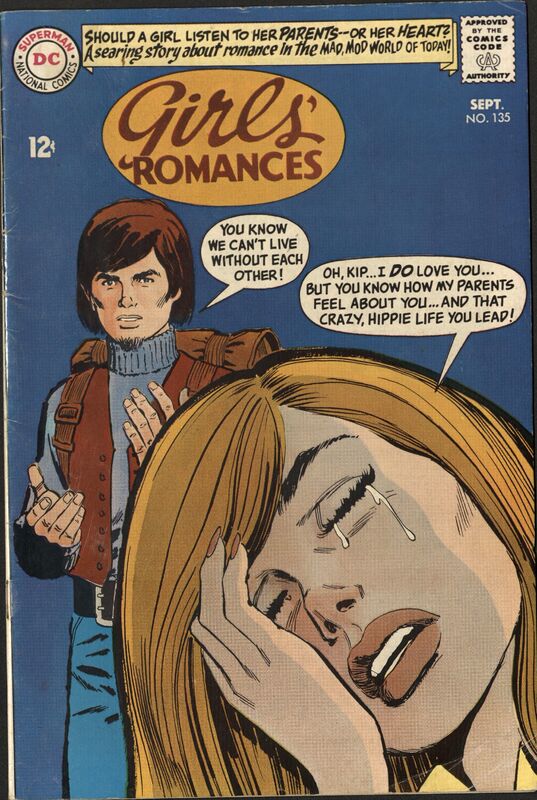

Girls’ Romances. No. 135, DC Comics, 1968.

This issue shows a woman crying because she loves a man named Kip but cannot be with him as his hippy lifestyle is in conflict with the values of her parents. Since the counterculture movement was primarily composed of young adults, this cover reflected the changing norms of the time and the generational conflict that subsequently arose. The crying woman carries the burden of choosing the values she will follow in the pursuit of love.

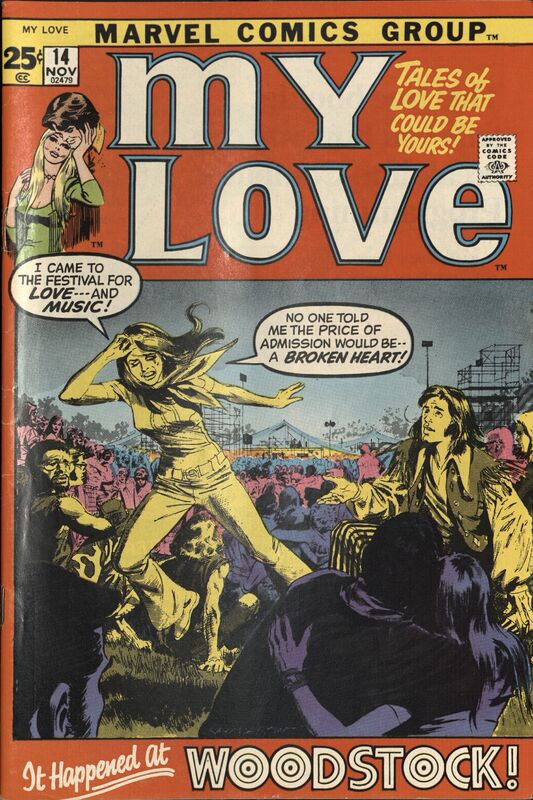

My Love. No. 14, Marvel Comics, 1971.

Although this comic book cover contains the crying woman, its presence is much more subtle. The focus of the front cover is the Woodstock Music Festival, which could capture the attention of a prospective buyer browsing the comic book rack. By implying that Woodstock resulted in the main character, the crying woman, experiencing heartbreak, this comic book sheds a negative light on youth culture – implying that such acts of ‘rebellion’ would instead hurt the ‘rebel’ in question.

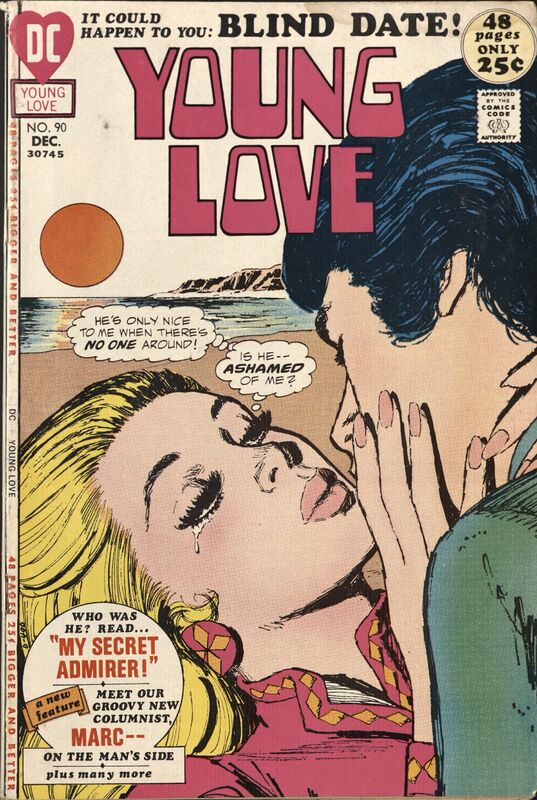

Young Love. No. 90, DC Comics, 1971.

This comic book issue shows a crying woman trapped in thought, questioning whether the man she is with is ashamed of their relationship. This cover stands out from other issues of the time period because the man and woman appear like they are about to kiss, but the woman’s hands are on the man's face and neck instead of the other way around. The crying woman is in control of the outcome of the romance . This is counter to the traditional belief that men were in control of the relationship, which illustrates the subtleties in romance comic books that came about during the Women’s Liberation Movement. The fact that the woman could be both crying and independent further highlighted the new, coming-about belief that emotion did not make a woman weak.

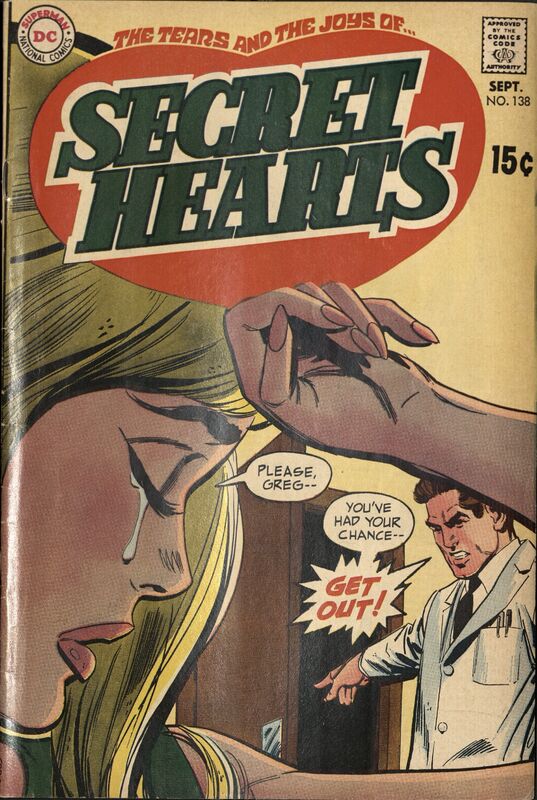

Secret Hearts. No. 138, DC Comics, 1969.

This issue stands out in its depiction of the dynamics between a crying woman and her boyfriend. The woman is begging her boyfriend for another chance, hoping that everything will work out between them, but her boyfriend remains adamant about her leaving. Her tears feel deeply emotional and sincere to the reader. This issue is the last is the series "Reach for Happiness," and the cover art is misleading. Like many romance comic plotlines, a woman was typically allowed to recover from a minor ‘mistake’ and have the ending work out in her favor. In this case, she asks her boyfriend to marry him and he says yes!

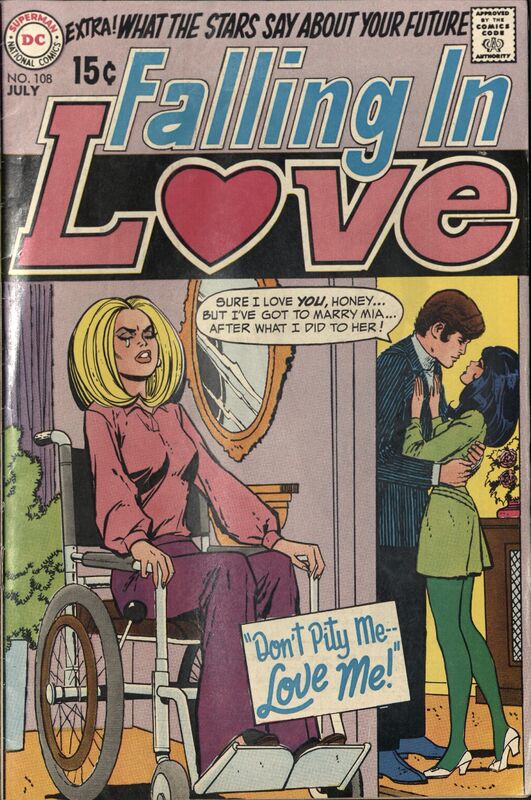

Falling in Love. No. 108, DC Comics, 1969.

The heroine’s tears convey the commonly encountered situations pertaining to love in which she clashes with external circumstances that are out of her control and serve as a barrier to love. She recognizes that she has become wheelchair-bound - a fate she can not fix - but at the same time, tries to stand up for what she believes in: a marriage of love rather than pity. Consistent with the Comics Code, the primary focus of the cover art is on the inner emotion rather than outer conflict. There is no direct or violent confrontation, and the cover is non-suggestive even with the couple standing to the side.

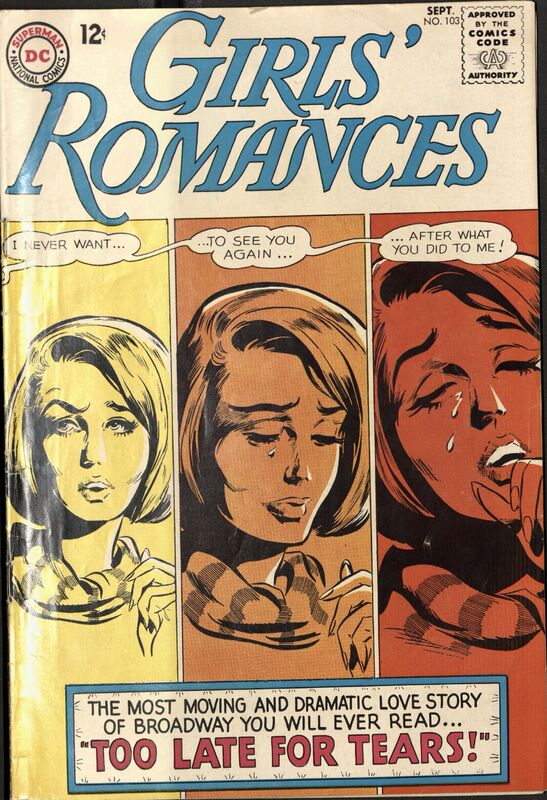

Girls’ Romances. No. 103, DC Comics, 1964.

In three panels, the cover art depicts a woman in a state of increasing emotional distress. The colors shift from a placid yellow to a deep red as the tears flow. Her tears indicate regrets for her actions, which is also supported by the line “too late for tears." The fine design of the cover shows how a comic book artist could hint at the drama and heartbreak to come in a story without revealing too much all the while abiding by the rules of the Comic Book Code.

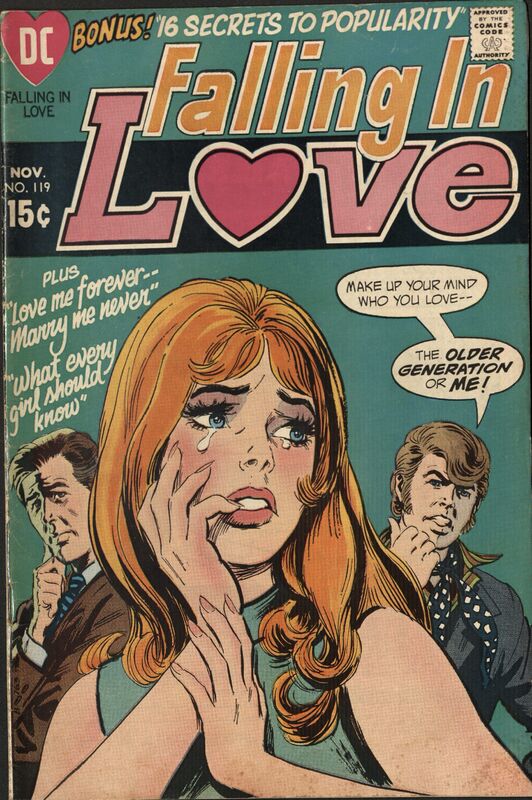

Falling in Love. No. 119, DC Comics, 1970.

A woman is crying with two men standing behind her. The younger man urges her to make up her mind and choose either him or the other much older man. The tears suggests that the woman struggles to choose , and this internal turmoil is the central conflict. Although the cover abides by the Comic Code, the fact that she is considering both suitors suggests to readers that it is okay to consider dating a much older man, which may be a bad message to young girls. Romance comics actively discouraged age-gap relationships, especially in their love columns.

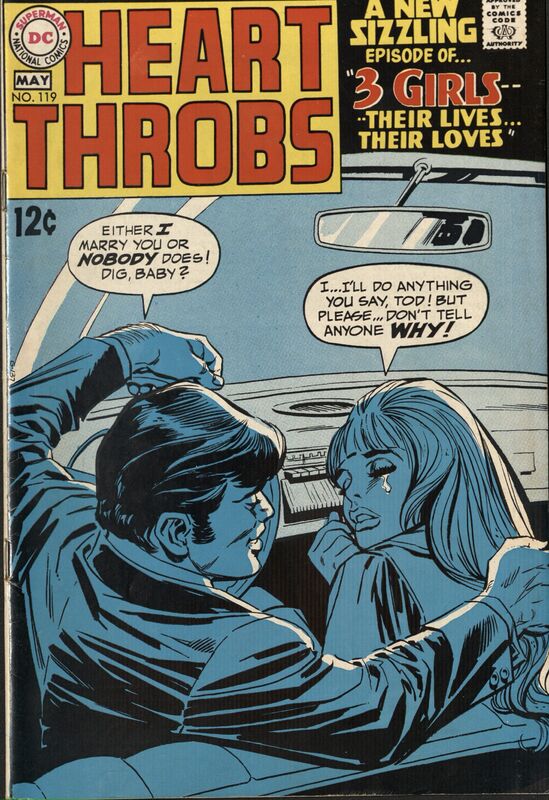

Heart Throbs. No. 119, DC Comics, 1969.

This cover of Heart Throbs shows a couple in conflict. The blue color, while suggesting nighttime, also fills the scene with sadness. The man threatens his date that either he marries her or nobody ever will. The young women cries, pleading that she’ll do anything for him. He doesn’t leave much of a choice for her to walk away from this toxic relationship. The act of crying is indicative of her loss of control and the inability to escape from escalating emotional abuse.